In August of 1939, Albert Einstein and other scientists sent a letter to then U.S. President Franklin Roosevelt warning of a Nazi program that could develop a nuclear bomb. In response to this threat, Roosevelt authorized the Manhattan Project to proceed under the guidance of General Leslie Groves, the development of America’s first nuclear weapon. President Roosevelt died on April 12th of 1945, and Harry Truman assumed his presidency, during the first month of which Victory in Europe (V-E Day) was achieved on May 8th of that year. But America was still at war across the Pacific theater against the forces of Imperial Japan, who had sworn to fight to the bitter end. Even as the Japanese stronghold on the South Pacific and East Asia was collapsing, children and women reported to factories on the Japanese homeland to make bamboo spears which would serve as a weapon of last defense once their modern weapons of war were exhausted. All Japanese men, women, and children were expected to fight to the death.

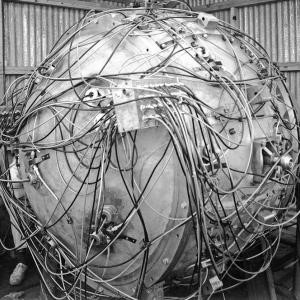

Back in America, President Truman was aware of the Manhattan Project and research proceeding under Dr. Robert Oppenheimer forty miles south of Socorro, New Mexico, near Los Alamos. It was the Trinity Test Site for the bomb. In a tower 103 feet above the ground, a large round object sat inside a small shed built atop the tower. It had many names; the gadget, the thing, the beast, the device, or simply “it.” Within 0.04 seconds of detonation, the steel tower was already vaporized. Observers of the blast described it as “beautiful and horrifying.” Regardless, news of the successful test reached President Truman where he was attending a meeting with Winston Churchill and Joseph Stalin in Potsdam, Germany.

Trinity test of the first atomic bomb, New Mexico, July 16th, 1945 at 5:29 am

The battle for Okinawa 400 miles southwest of Japan had seen brutal, hand-to-hand combat over three weeks, leaving 12,000 American soldiers dead. The Japanese lost 107,000. The plan to invade the southern island of Japan on November 1st expected American forces to face 350,000 Japanese troops, and General George Marshall, Chief of Staff, had estimated 31,000 American troops would be killed in just the first three days of the assault. For President Truman, the decision was an easy one. This new weapon would bring the Japanese to their knees and achieve a quick and total Japanese surrender. More importantly, it would save thousands of American lives.

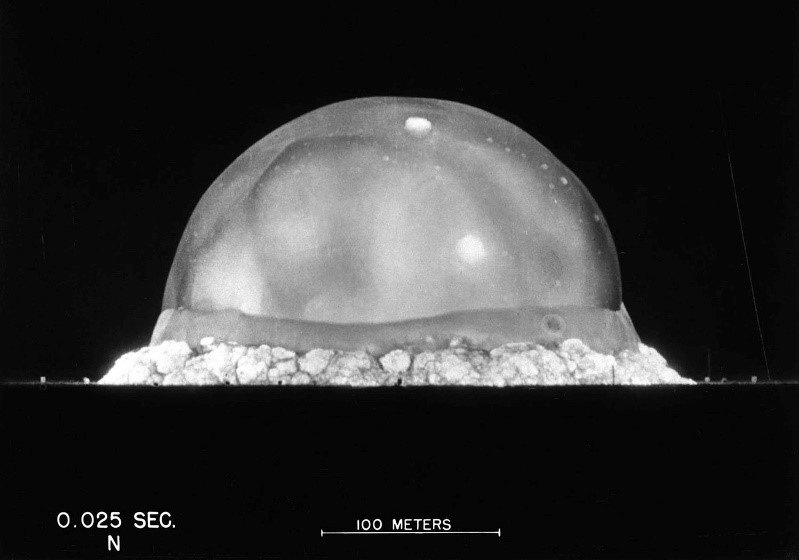

At Hunters Point Naval Shipyard in San Francisco, sailors aboard the U.S.S. Indianapolis watched in the morning hours of July 16th as two packages arrived under heavy guard at the dock and were loaded onto their heavy cruiser. Captain Charles McVay had orders to proceed at high speed to Tinian Island airfield, 1,500 miles south of Japan. His orders were to deliver his top-secret cargo, the bomb housing, and the load of weapons-grade uranium that would comprise “Little Boy.” This was the fearsome atom bomb that would be dropped on Hiroshima, Japan. The crew of the U.S.S. Indianapolis had no idea what its mission was. They only knew that it was heavily guarded, and they were going somewhere in a big hurry.

U.S.S. Indianapolis (CA-35) Heavy Cruiser off Mare Island, San Francisco, CA, July 1945

76 hours after departure, she was in Pearl Harbor, refueled and restocked, and got underway again without any crew allowed to leave the ship. In less than ten days after leaving San Francisco Bay, the Indianapolis dropped anchor at Tinian Island. Her mystery cargo was off-loaded for delivery to the 509th Composite Group, a squadron of Boeing B-29 Superfortress crews and their planes. The Superfortress crews were training for their “special mission” over Japan, even though they weren’t sure what it was.

Captain McVay now received new orders to join Task Force 95.6, a massive assembly of the U.S. military at Leyte Island in the Philippines to prepare for the invasion of Japan. Though relieved to be rid of their top-secret cargo, the crew of the Indianapolis had no idea of the fate that awaited them while crossing 1,300 miles of the Philippine Sea alone.

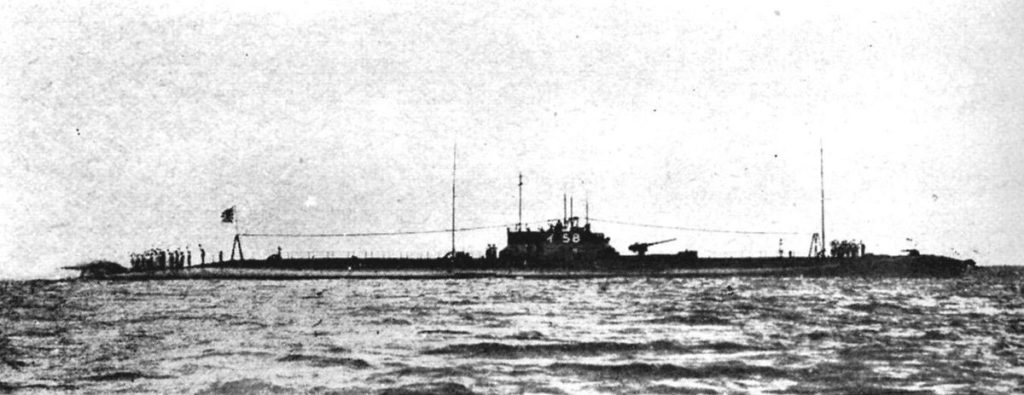

On Sunday, July 29th, having left Guam and heading west, she was spotted by a Japanese submarine, I-58, under the command of Lt. Cdr. Mochitsura Hashimoto. He immediately dove his sub to periscope depth. He fired a spread of six type-95 torpedoes at two-second intervals at the U.S. ship that was making way without following the usual zig-zag pattern ships used to avoid torpedo attack. Hashimoto saw two torpedoes hit.

Imperial Japanese Navy Submarine I-58 (IJN I-58)

Back aboard the Indianapolis, the two explosions rocked the vessel. One sailor reported looking forward, and it appeared that the bow was gone. The ship listed heavily to starboard and sank in twelve minutes. The crew had a compliment of 1,197 souls on board. An estimated 300 went down with the ship, with the other 897 men going into the sea. Many were severely burned and injured. Others were covered in oil and feared the fire would consume them. Very few had time to gather life jackets and launch lifeboats. The radio operator had made a hasty call for help, but due to the top-secret nature of their previous mission, no one was looking for them, and no one knew where they were. More importantly, the few who heard their call for help ignored it, thinking it was a Japanese trick. Another officer who listened to the call was drunk and did not respond.

The crewmen huddled together in groups to help each other stay afloat as their first night in the water began at approximately 11:30 pm. But they soon learned that they were not alone. The Japanese submarine had departed heading north, not bothering to check for survivors, but it was now that the sharks came, and they came in large numbers. As the men in the water were attacked, they would splash and kick and punch at the sharks, and sometimes the sharks would swim away, but more often, they would drag the men under. When daylight came, the sun bore down upon their heads for hours without relief, and the water, as one survivor described it, was like wearing a mirror under your chin, your head being slowly roasted. And still, the sharks came. The men would pray for the night to come to relieve them of the burning sun but then pray for the day so they could see the sharks. The crew of the Indianapolis remained in the water for four and a half days, struggling to stay afloat, struggling to stay alive. There was no food or water. The sun and the sharks continued to do their work. Some drank salt water and became violently ill and incoherent. Some lost hope and gave up, drifting away from the group until the sharks took them—the men of the U.S.S. Indianapolis lived in a nightmare that would not end, and they quickly lost strength and hope.

On the morning of August 2nd, a Lockheed PV-1 Ventura flown by Lieutenant Wilbur “Chuck” Gwinn spotted the men in the water while on a routine patrol. They flew low over the remaining men and dropped a life raft and a radio transmitter to them while they radioed their position. All available surface and air units responded immediately. First on the scene was a PBY-5A Catalina Piloted by Lt. Cdr. Robert A. Marks. He disobeyed orders not to land and put his giant seaplane down in 12-foot swells, damaging the aircraft in the process. He and his crew immediately began pulling men out of the water and into the plane and lashing them to the wings when there was no more room inside the plane. They saved 52 souls.

PV-1 Lockheed Ventura (left) and a Consolidated Aircraft P.B.Y. Catalina (right)

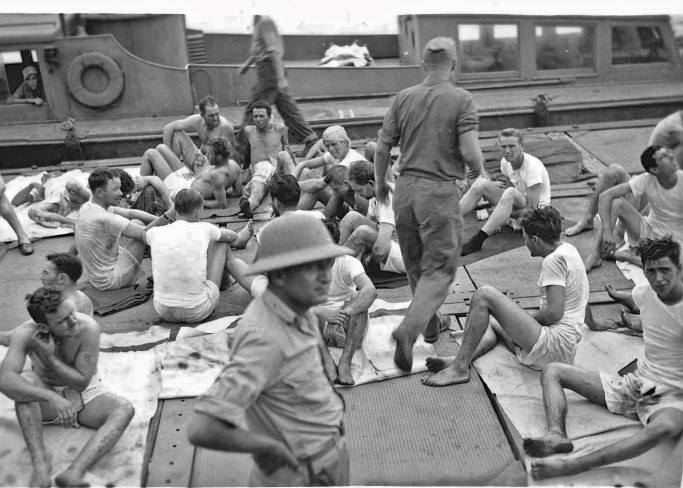

Photo of survivors in the water. Three sharks can be seen swimming among the men.

After the recovery mission was over, of the approximately 897 men who went into the water, only 312 came out. It has been estimated the majority died of exposure, hypothermia, hyponatremia, and many killed themselves from delirium and dehydration. Still, the Indianapolis incident has been recorded as the worst shark attack in human history and the worst sea disaster in U.S. Naval history.

Survivors of the U.S.S. Indianapolis being treated on Guam and aboard rescue vessels

A few days later, on August 6th, at 9:30 am, the crew of the B-29 Enola Gay flown by Colonel Paul Tibbets dropped “Little Boy” over Hiroshima, Japan. The bomb performed exactly as planned, detonating at the optimum altitude of 1,850 feet, sending a shockwave that flattened every structure in the city with a force of seven tons per square meter and reached temperatures of 60 million degrees centigrade, 10,000 times hotter than the surface of the sun. Total Japanese surrender followed soon after. Victory over Japan Day (V-J Day) is officially marked on September 2nd, 1945, when the Japanese Imperial forces signed surrender documents aboard the U.S.S. Missouri. It is vitally important to remember these events and tell them to the next generations, as difficult as that may be so they can hopefully avoid repeating the same man-made horrors in the future.

For most of us who grew up after the war, we first heard about the U.S.S. Indianapolis, not from history books, but from actor Robert Shaw in Steven Spielberg’s 1975 blockbuster movie “Jaws,” based on the 1974 book of the same name by Peter Benchley. In the film, a shark hunter named “Quint” tells the story of the Indianapolis to co-stars Richard Dreyfuss and Roy Scheider in the cabin of the “Orca,” Quint’s boat while out hunting the great white shark. According to Spielberg, the scene became the film’s defining moment and had audiences transfixed as Shaw “brilliantly relates the story.” You can easily find it online and listen.

It remains Spielberg’s “favorite scene in the film.” It serves to educate those who are not much interested in history, hopefully driving them on to find out what really happened in the southern pacific so long ago, along with other stories of the valiant deeds of our nation’s men and women in uniform, in service to their country. These stories must be preserved, and we should never forget them.

U.S.S. Indianapolis CA-35 Memorial, Indianapolis, IN, Indiana War Memorials Foundation

*unless otherwise noted, all photos are in the public domain.

*Shockwave, Countdown to Hiroshima by Stephen Walker, copyright Harper Collins 2005, provided invaluable information for this article.