(Photo credit: Mark Krancer)

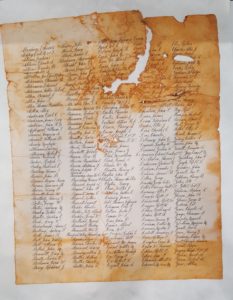

Memorial Park is a historic city park located on the north side of the St. Johns River in Jacksonville, Florida. Following World War I, the Rotary Club of Jacksonville created the park to commemorate the Floridians who died in WWI, with a large copper statue serving as a memorial. At the statue’s base, a time capsule was interred on December 24, 1924, containing a scroll with a list of the Florida men and women who lost their lives during the war.

(Photo credit: Mark Krancer)

In 2018, the Memorial Park Association decided to pull the time capsule after Dr. R.B. Rosenberg of Clayton State University determined more names should have been included. During the removal, it was determined the time capsule had filled with water, likely when the park flooded following Hurricane Irma. Due to the waterlogged condition of the scrolls inside the capsule, it was brought to the Charles G. Cox Conservation Lab at the St. Augustine Lighthouse & Maritime Museum. Underwater archaeologists from the Museum’s research arm, the Lighthouse Archaeological Maritime Program (LAMP), often dive off the coast of northeast Florida to survey and have found several shipwrecks. The conservation team supports LAMP’s efforts by restoring many artifacts they recover. While shipwrecks contain a variety of objects, paper is not commonly found. Because of its lightweight and delicate nature, paper is often one of the first things to deteriorate or float away unless surrounded by sediment or other objects. Luckily, the Memorial Park Association had already found a paper conservator who formerly worked at the National Archive.

(Photo credit: Mark Krancer)

Sharing the lab with Guest Conservator Ann Seibert was a learning experience. The scrolls came out of the time capsule as a lump of wet paper with rust and sediment stains. Ann kept the paper wet to slowly straighten the stack of 6 pages. Next, she used the surface tension of water and polyester sheets to peel the layers of paper apart. In doing so, we discovered a paperclip that was the leading cause of the rust stains. She then proceeded to wash the paper gently with water flushes and a small paintbrush. Once the paper was clean enough to read, it was slowly air-dried and painstakingly mended using chemicals and paper specifically designed to help with paper stabilization. The scrolls, which started as a lump of wet paper, are mostly intact, with almost all 1,220 names legible.

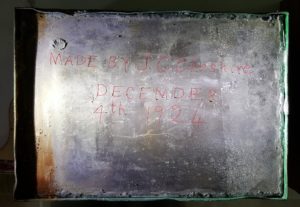

The two boxes that made up the time capsule, a lead inner box and copper outer box, took much longer to conserve. The copper was covered in concrete from how the box was interred in the statue’s base. Unfortunately, concrete is acidic and would slowly eat away at the copper over time. A chemical process would have cleaned the box faster but also removed the patina. A patina is a stable layer of corrosion that gives copper a green to black color. Concrete was slowly scraped away while avoiding the removal of the patina to preserve the box and keep it in the best condition possible. In some areas, the concrete was thin and easy to remove, but in others, it was close to a quarter of an inch thick and refused to come off without a large amount of coaxing. Once the concrete was finally removed, the copper box was put in a chemical solution to stabilize the copper, prevent further corrosion, and then sealed with wax. The lead box was a bit quicker. It was cleaned with hydrochloric acid and then sealed with wax.

(Pictured Left: Top of the inner lead box with a highlighted message from the maker. Pictured Right: (Pictured: The outside of the copper box covered in concrete.)

It has been our pleasure to work with the Memorial Park Foundation to help preserve a part of Florida’s history. While our main focus is the maritime history of the First Coast, it is always fun to work with other community members on expanding the overall history of our area. With conservation complete, the scrolls and boxes were returned to the Memorial Park Foundation. On November 13, 2021, the items were displayed in an exhibit at the Museum of Science and History (MOSH) in Jacksonville. The exhibit is called “The Life Scrolls: A Tribute to Florida’s World War I Fallen.” Visit the Memorial Park in Jacksonville and the Conservation Lab at the St. Augustine Lighthouse & Maritime Museum to learn more.