In the months immediately following the December 7th attack in 1941 on the American Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, American resolve was codified into a call for action. Something had to be done quickly to send a message to Imperial Japan that they were not out of our reach. Payback was coming.

In this photo is what appears to be a Japanese Aichi D3A1 Dive Bomber taking up an attack angle for another run at Battleship Row; U.S. Navy battleships at anchor along the Southeast edge of Ford Island, Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, December 7th, 1941.

On December 21st, 1941, President Franklin D. Roosevelt assembled his Joint Chiefs of Staff and said that an attack on the Japanese homeland should be accomplished as soon as possible. This was to help bolster American morale and place doubt in the minds of the Japanese people about the competency of their leadership. On January 10th, 1942, Vice Chief of Staff, Navy Captain Francis Low, reported that he had seen twin-engine Army bombers attempt to land on an area the size of an aircraft carrier at Norfolk, Virginia, where runway areas had been measured to that distance. He thought that they could be launched the same way. The assignment to plan the raid was given to Lt. Col. James H. “Jimmy” Doolittle, an aviation pioneer, and military test pilot. Doolittle reviewed the available candidates for the mission and quickly chose the Mitchell B-25B for the task.

Lt. Col. Jimmy Doolittle Mitchell B-25B, Medium-Range Bomber

The B-25 only had a range of 1,350 nautical miles and so would need to be modified to carry enough fuel for its crew of five, a 2,000-pound bomb load, fly 2,400 nautical miles, and still be able to take off from a carrier deck at sea. It was a tall order but would prove to be one of the most daring missions of the war and a mission that would be a one-way trip with plans to land in China or the Soviet Union. There would be no chance to return to the aircraft carrier—many thought of it as a suicide mission. Pilots from the 17th Bomber Group were chosen and simply given a choice to volunteer for “an extremely hazardous mission.” No details were given, and tight security was maintained for the entire project. The men who volunteered were nicknamed “Doolittle’s Raiders.”

Changes to the aircraft included removing the bottom gun turret and installing mock twin machine guns in the tail gunner’s position to save on weight. An extra 160-gallon collapsible fuel tank was installed above the bomb bay, and the center radio position was eliminated. The expensive Nordon Bombsight was removed, and a make-shift sighting tool was invented and installed that cost only twenty cents in materials to build. It was nicknamed the “Mark Twain.” Each plane would carry three 500-pound bombs and one bomb filled with incendiaries.

It is here that our story moves to Florida. Twenty-two crews were flown to the factory in Minneapolis to pick up the modified planes and then flew them to Eglin Field at Naval Air Station Pensacola in early March of 1942. Eglin Auxiliary field #1 (later named Wagner Field after U.S.A.A.F. Major Walter J. Wagner) was situated Northeast of the main base and was used for Doolittle’s Raiders’ primary training to master take-off within the short distance that would be their runway aboard the aircraft carrier.

1949 Aerial photo of Eglin Aux. Field #1, Florida, where horizontal markings across the runways can be clearly seen to provide the Doolittle Raiders with reference points for carrier take-off distances. The markings could still be seen in an aerial photo taken of the same runways in 2006.

The practice was daily and constant in locking the brakes on the main gear and running up engines to the required R.P.M. before releasing the brakes and hoping to be airborne before crossing the line of demarcation. The training was supervised by Lt. Henry Miller, a flight instructor from N.A.S. Pensacola, who eventually shipped out with the crews to assist with a take-off on the actual mission. He formally became a member of Doolittle’s Raiders even though he did not actually fly the mission.

Doolittle B-25 crew practices take-off at Wagner Field, Pensacola, Florida, 1942

Ultimately, sixteen of the original crews shipped out aboard the aircraft carrier U.S.S. Hornet and Task Force 18 from San Francisco on April 1st, 1942, headed west. This group joined up with aircraft carrier U.S.S. Enterprise and Task Force 16 and proceeded toward Japan. It would be the job of the U.S.S. Enterprise’s fighters provided air cover for Hornet from a Japanese air attack since Hornet’s deck was covered with the bombers, and all of her fighters were stowed below deck.

B-25 B’s on the flight deck of the U.S.S. Hornet, April 1942

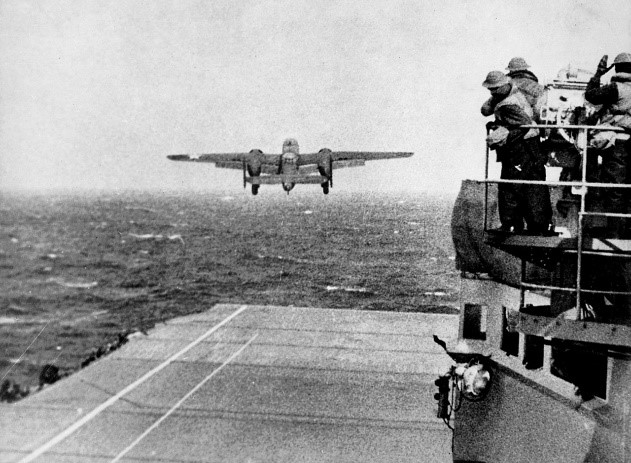

On April 18th, the group was spotted by a Japanese Imperial Navy patrol boat that sent a radio warning to Japan. American forces immediately sunk the boat, but the group was 170 nautical miles from their original planned launch distance. Nevertheless, they decided to launch the planes at once. The reality for the crews was that they could reach Japan, but not necessarily their planned landing in China. They would run out of fuel before they got there. Lt. Col. Doolittle Piloted the first plane into the air, and all sixteen planes launched successfully.

A Raider launches from the deck of U.S.S. Hornet. Later, the flight group is photographed over the island of Japan. The bombing run over Tokyo would last only thirty seconds.

The mission continued with the successful bombing of industrial targets in both Tokyo and Yokohama. Then most of the crews ditched their planes in the South China Sea. The mission, by all standards, was a success and shocked the residents of the Japanese homeland in a prophetic way of what the result of the war would be with American bravery and resolve.

The mission was immortalized in a book written by Capt. Ted W. Lawson, one of the original Doolittle’s Raiders pilots, and subsequently in a movie produced by M.G.M. Studios starring Spencer Tracy, Van Johnson, and Robert Mitchum called “Thirty Seconds Over Tokyo,” released in 1944. But many of the men who accomplished this incredible feat at the outbreak of the war had their initial flight training in South Florida and then returned to Pensacola for the specialized training required of them to perform an impossible mission that their country had asked of them. Once again, the State of Florida provided essential service to the men of WWII.

Images from Thirty Seconds Over Tokyo, Copyright M.G.M. Studios, 1944

*Unless otherwise noted, all images are in public domain