At one point in history, it was unheard of for women to go to war. The movie industry reinforced depictions of the stereotypical wife or sweetheart remaining home, crying into her hanky while her man went off to war, time and time again. The actual reality of those times is anything but that. It is estimated between 400 and 750 women disguised themselves as men and fought on the front lines during the American Civil War, only to be discovered later at a field hospital where they were treated for battle wounds.

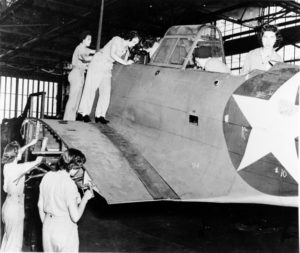

At the outbreak of World War II, America had never faced such daunting challenges of producing war materials and mobilizing millions of men into the armed services. The void left in manufacturing was massive, and America’s women did not hesitate to fill it. As many as 6 million women entered the workforce for the first time, and an estimated 2 million worked in manufacturing through building ships, airframes, artillery pieces, and ammunition for the troops overseas.

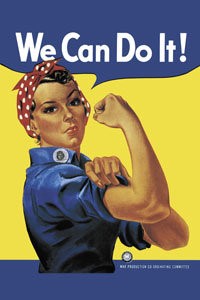

Women go to work in U.S. shipyards, aircraft, and armament factories

Shipyards in Miami, Tampa, and Jacksonville, Florida, were flooded with these new workers. “Rosie the Riveter” became the national symbol for the recruitment of women needed to work in these vital positions. Women were doing the same jobs historically reserved for men and smashing long-held prejudices and stereotypes in the process. However, the process of advancing roles for women was not their primary motivation.

Like the women fighters of the Civil War, they simply wanted to do their part, as Americans, to rid the world of the threat from the Axis of Evil that threatened free people everywhere. These women crossed racial and social boundaries, and many saw their first paycheck earned from the work of their hands, and the sweat of their brow, in the effort.

In Florida, the tourism industry was booming during the pre-war years, particularly on Miami’s sunny beaches. Simultaneously, hunting and fishing in the central part of the state, along with the panhandle, were just as sought after as the sunshine. St. Augustine was particularly popular with its historic architecture, hotels, and pristine beaches and seafood. In 1940, Marineland, just south of St. Augustine, was the most popular attraction in the state. But with the coming of war, the tourism trade disappeared almost overnight. The small coastal cities of St. Augustine and Daytona, and many others, were on the verge of financial ruin.

In St. Augustine, a new U.S. Coast Guard training center for both men and women (SPARS) was established, which brought much-needed income into the city. But in Daytona, the city leadership scrambled to find a way to bolster their own city’s economy. The answer came from a well-known and respected civic leader named Mary McLeod Bethune. Bethune, a native of Palatka and child of slaves, had moved to educate herself, benefiting from the post-Civil War efforts to educate black Americans.

Bethune would later establish a boarding school in Daytona to train African-American girls, eventually becoming a women’s college. Cookman College for African American men was there too, and the schools merged to become Bethune-Cookman College. Bethune became good friends with Eleanor Roosevelt and eventually became the highest-ranking African American woman in government.

Mary McLeod Bethune

It was no surprise then that Daytona city leaders came to Mary Bethune asking for help. It is said she listened quietly, then lifted her phone and called President Roosevelt directly. The result established a major training facility for the Women’s Auxiliary Army Corps (WAAC) in Daytona. Bethune was named to the WAAC Advisory Board and served President Roosevelt as an Advisor on African-American Affairs. The headquarters were established at the Wingate Building downtown, and initial recruits were housed in the Osceola Hotel.

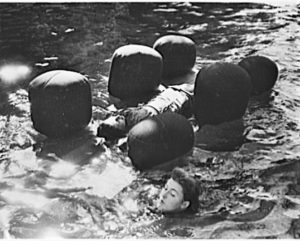

Life-Saving Class, WAAC Training Center, Daytona Beach

Soon, women from all over the United States began pouring into Daytona for training in many active-duty capacities. Twenty thousand would eventually train in the city and then move on to other assignments and duty stations. It is said that WAAC parades through the city and exercise sessions on the beach became popular spectator activities for the locals and service members visiting the city. The establishment of the base brought an estimated 5 million dollars a month to the city’s income, which is an equivalent of 93 million a month today.

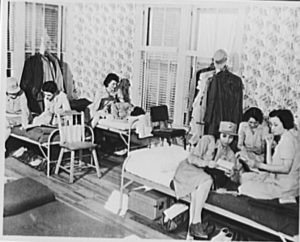

Chow-time and Sunday downtime for the Florida Recruits

Troop Inspection, Daytona Beach. WAAC was later changed simply to WAC (Women’s Army Corps)

Women in the skies

Meanwhile, a young woman raised in poverty in Pensacola would make a name for herself in a big way for the war effort. Jacqueline “Jackie” Cochran took her first ride in an airplane in the 1930s after leaving Florida to pursue a successful career in the women’s cosmetic industry. She was immediately hooked on flying and, in three weeks, earned her pilot’s license. Within two years, she acquired her commercial pilot’s license, competing in and winning air races, having worked with Amelia Earhart to open the historically male competitions to women. By 1938, she was considered the best female pilot in the United States.

Jackie Cochran in the cockpit of a Curtiss P-40 Warhawk and later portrait from WWII

Prior to the U.S. entering the war, Cochran became the first woman to pilot a bomber, a Lockheed Hudson V, across the Atlantic for the British Air Transport Auxiliary (ATA). She then recruited other American women pilots to join the ATA and eventually achieved the rank of Squadron Leader in the British Royal Air Force. While Cochran was in England with 76 hand-picked female pilots serving the ATA, other civilian female pilot groups were formed in America to ferry planes from factories to the coasts to free up male pilots to serve when America formally entered the war. Among these were the Women’s Auxiliary Flying Squadron (WAFS) and the Women’s Flying Training Detachment (WFTD), which trained female pilots for non-combat flying.

Cochran, newly returned from England and anxious to serve her own country, was appointed to head the WFTD. In 1943, the two entities merged to form the Women’s Airforce Service Pilots (WASP) with Cochran in command of the entire U.S. training program and another female pilot, Nancy Love, to head the aircraft ferrying wing. Under Cochran’s leadership and direction, hundreds of American women were trained to fly and transport aircraft all across the United States and fly other vital missions for supply, communications, troop transport, and intelligence for the war effort.

American women train alongside men WASP trainee class with Jackie Cochran (center)

Cochran and the WASP program met with resistance from politicians and the public, who thought that the area of military aviation should remain squarely in the hands of men. Because it was a civil volunteer organization, unlike men in the military, these women had to pay for their transportation to the training centers, room and board, and uniforms. Eventually, a total of 1,830 female pilots served in the WASP program. They flew every type of plane the Army Air Corps had. They served as test pilots for repaired aircraft to ensure they were safe before handing them over to male cadets. The only formal WASP airbase in Florida was Buckingham Army Air Field in Fort Myers.

The other famous Florida woman to serve as a WASP was Deanie Parrish from Avon Park. She obtained her pilot’s license as a teenager and signed up for service at age twenty-one, determined to serve her country the best way she knew how. She remembers one of her most dangerous and memorable assignments happened at Tyndall AFB in Panama City. Parrish was to fly a B-26 Martin Marauder while towing a target for gunnery trainees on the ground. It was risky due to the inexperience of the trainees shooting live ammunition at the target, and some of the rounds ended up in the tail of her aircraft.

When she finished her service, which was extensive, she had to pay her way back home. Like all the other female volunteers, she received no recognition, no GI benefits, but only the satisfaction she had done her part to serve her country and contribute to the war effort. Her efforts later in life to bring recognition to the program with exhibits and lectures resulted in her receiving the Congressional Gold Medal, the nation’s highest civilian honor on behalf of all WASPs, in Washington D.C. in 2010.

Deanie Parrish, Tyndall Field in front of a P-47 Thunderbolt, 1944

Women answered the call of the U.S. Navy, serving with the WAVES (Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service), and trained as nurses in Hollywood, Florida, and in Naval Aviation at U.S. Naval Air Station in Jacksonville.

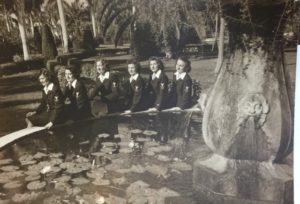

WAVEs pose for a photo in Hollywood, FL, and WAVE aircraft mechanics working at Naval Air Station Jacksonville

All across Florida, women came to serve in every conceivable job to contribute to the war effort; WAACs in the U.S. Army, WASPs in the Army Air Corps, WAVEs in the U.S. Navy, and SPARs in the U.S. Coast Guard, as well as thousands of women who worked in factories, without fancy uniforms or command inspections. They simply saw the need and responded accordingly. The United States and its allies could never have won WWII without the significant contributions, tireless work, dedication, and devotion to duty from women. These were the women of WWII.

An unknown welder works at St. Johns River Ship Building, Jacksonville, FL

*All photos are in the public domain

Do you have a story of a WWII Female Veteran? Please share it with Museum Educators. Contact gballard@staugustinelighthouse.org. We would love to hear from you and don’t forget to Visit, Join, or Donate to our non-profit organization.

About the Author: Rick Cain

Rick Cain has worked for the St. Augustine Lighthouse & Maritime Museum for 18 years after a 20-year career as a health care professional.

He serves on the Board of Directors of the American Lighthouse Council and is Immediate Past Chair of the Florida Attractions Association. He also works closely with the United States Coast Guard to maintain their historical ties to the Museum.