It is with a heavy heart that we announce the passing of George Fischer on Sunday May 29th, 2016.

George was my teacher and mentor, as he  was for countless other archaeologists who took his classes at Florida State University between the 1970s and 1990s and into the early 2000s. George founded the underwater archaeology program in the U.S. National Park Service, which was first operated from the Southeast Archaeological Center in Tallahassee before the formation of the Submerged Cultural Resources Unit (now the Submerged Resources Center). He was also a founding member of the Advisory Council on Underwater Archaeology, which currently exists as an international committee of the Society for Historical Archaeology. He began teaching underwater archaeology classes at Florida State University in 1974, and was named a Courtesy Assistant Professor in 1988 upon his retirement from the National Park Service. He taught underwater archaeology and scientific diving classes at FSU every year for almost 30 years. He was an inspiration for at least two generations of underwater archaeologists, who now comprise many leaders in the field working professionally in the private sector, as government archaeologists, in the museum community, and in academia. Many of us have the privilege, as George did, of shaping the next generation of maritime archaeologists.

was for countless other archaeologists who took his classes at Florida State University between the 1970s and 1990s and into the early 2000s. George founded the underwater archaeology program in the U.S. National Park Service, which was first operated from the Southeast Archaeological Center in Tallahassee before the formation of the Submerged Cultural Resources Unit (now the Submerged Resources Center). He was also a founding member of the Advisory Council on Underwater Archaeology, which currently exists as an international committee of the Society for Historical Archaeology. He began teaching underwater archaeology classes at Florida State University in 1974, and was named a Courtesy Assistant Professor in 1988 upon his retirement from the National Park Service. He taught underwater archaeology and scientific diving classes at FSU every year for almost 30 years. He was an inspiration for at least two generations of underwater archaeologists, who now comprise many leaders in the field working professionally in the private sector, as government archaeologists, in the museum community, and in academia. Many of us have the privilege, as George did, of shaping the next generation of maritime archaeologists.

The first underwater archaeology project George directed was a survey of Montezuma’s Well in October 1968. This was one of the earliest of such projects to be carried out in the U.S. George also served as the project coordinator for the excavation of the 1865 steamboat Bertrand in 1969, and was involved with the investigation of the 1554 Padre Island wrecks the following year. He directed research projects in the Dry Tortugas, including surveys of National Park waters and investigations at Fort Jefferson and at the alleged site of the 1622 galleon Rosario shipwreck, between the 1960s and 1980s. On July 4, 1980, Fischer’s team discovered the remains of the British warship HMS Fowey, in the waters of Biscayne National Park. The subsequent investigation and identification of this shipwreck is considered by many of his students to be the highlight of George’s career; we certainly remember his “magic lantern” slideshows on the project. Its story is told in the book co-authored by George and his former student, Dr. Russ Skowronek, “HMS Fowey Lost and Found,” published in 2009. This is a great read for those who don’t yet have it on their bookshelf.

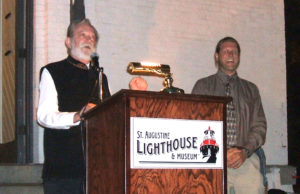

At the end of his career, many of  George’s students were delighted to see him recognized for his contributions to the field. On March 21, 2007 my institution, the St. Augustine Lighthouse & Maritime Museum and the Lighthouse Archaeological Maritime Program, honored him with a Lifetime Achievement Award for his “many contributions to the field of underwater archaeology, and to the education of this and future generations of underwater archaeologists.” George’s personal library is now part of the permanent collections at the St. Augustine Lighthouse & Maritime Museum, which is fitting given that George directed the first underwater archaeological research in St. Augustine, the nation’s oldest port. In 2008 a session of papers in honor of George–titled “The Wrecks We’ve Gone Down On”–were presented at the 41st annual SHA Conference on Historical and Underwater Archaeology held in Albuquerque, New Mexico, located close to his earliest work on Montezuma’s Well. On January 8, 2010 George was presented with the Society of Historical Archaeology’s Award of Merit for “his many contributions to the development of underwater archaeology and for his exemplary service on the Advisory Council on Underwater Archaeology.”

George’s students were delighted to see him recognized for his contributions to the field. On March 21, 2007 my institution, the St. Augustine Lighthouse & Maritime Museum and the Lighthouse Archaeological Maritime Program, honored him with a Lifetime Achievement Award for his “many contributions to the field of underwater archaeology, and to the education of this and future generations of underwater archaeologists.” George’s personal library is now part of the permanent collections at the St. Augustine Lighthouse & Maritime Museum, which is fitting given that George directed the first underwater archaeological research in St. Augustine, the nation’s oldest port. In 2008 a session of papers in honor of George–titled “The Wrecks We’ve Gone Down On”–were presented at the 41st annual SHA Conference on Historical and Underwater Archaeology held in Albuquerque, New Mexico, located close to his earliest work on Montezuma’s Well. On January 8, 2010 George was presented with the Society of Historical Archaeology’s Award of Merit for “his many contributions to the development of underwater archaeology and for his exemplary service on the Advisory Council on Underwater Archaeology.”

As a colleague has written upon hearing the news of his death, George was a legend. His antics included fireworks in SHA hotel stairwells, sword cane incidents in university hallways, inappropriate photographs in government offices, and others that won’t be repeated here. He survived motorcycle and diving accidents and long-time but eventually abandoned bad habits of drinking and smoking. He could be a little rough around the edges for bright-eyed students of the 1990s at the introduction to college campuses of political correctness. He was never afraid to speak his mind even if it cost him political points, and he adorned his office wall with official bureaucratic reprimands like red-taped badges of courage. On the day of his death he told his wife that the thing he was most proud of was his students. We learned from him of archaeology and anthropology and life, and we loved him, and we will proudly carry on his legacy. We will sorely miss him.

Chuck Meide