In the previous blogs, I have discussed the varied and lengthy conservation techniques of Storm Wreck pieces.

Typically, these methods start from the moment a site is discovered and an artifact is disturbed. Once the immediate environment and surroundings have changed, an artifact will start going through new corrosion changes. Students and/or LAMP divers have to treat objects very carefully underwater while they are dredging and carrying them up to the surface.

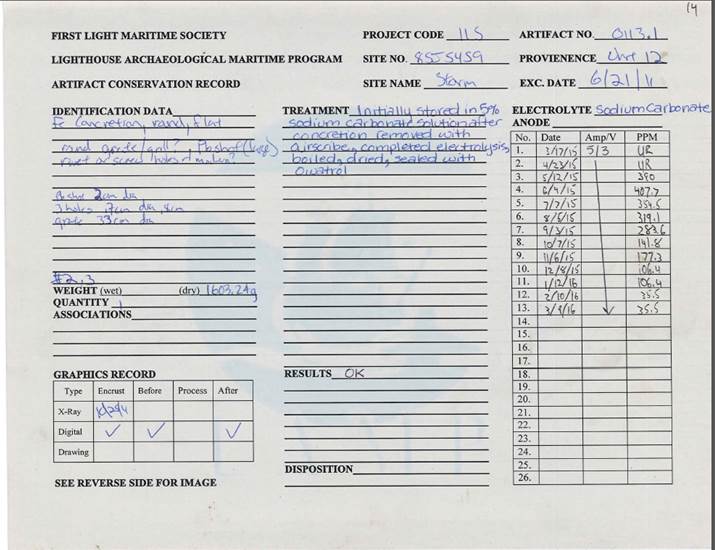

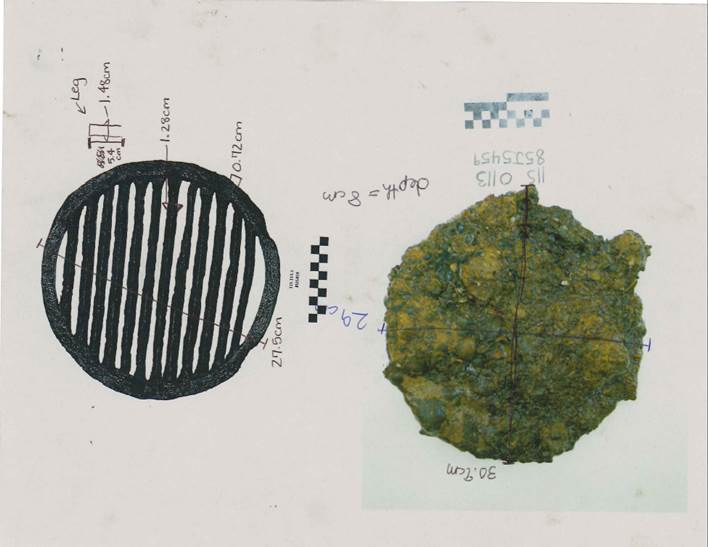

Once on the boat they are documented to show the condition immediately after excavation and numbered. Back on shore, they are then taken to be x-rayed and identified. Next is the long process of removing the concretion and the chlorides from the artifact. This is the phase most people think of when broaching the subject of conservation. It is also what visitors can expect to see when touring the Lighthouse grounds and coming over to the conservation area. The final active conservation step is to rinse and coat the artifact with a sealant so that it is stable and may be exposed to the environment.

However, the conservation process is not done. The artifacts on display in the new Wrecked! exhibit all went through one form or another of the aforementioned steps, but still have more work to be done on them. Even though they have been treated and are in the museum, they require monitoring and care from the conservation and collections staff.

Once an artifact is sealed and ready to go, they need to have final documentation such as measurements, photos and treatment methods written down. These notes, as well as any other relevant information, are added to our database and the State of Florida’s using a program called PastPerfect. Once they are catalogued with the state, the conservation staff hands the artifacts to the Lighthouse Collections department. Collections will then coordinate on what objects stay with the Lighthouse Museum and what are sent to Tallahassee to be added to the state’s assemblage.

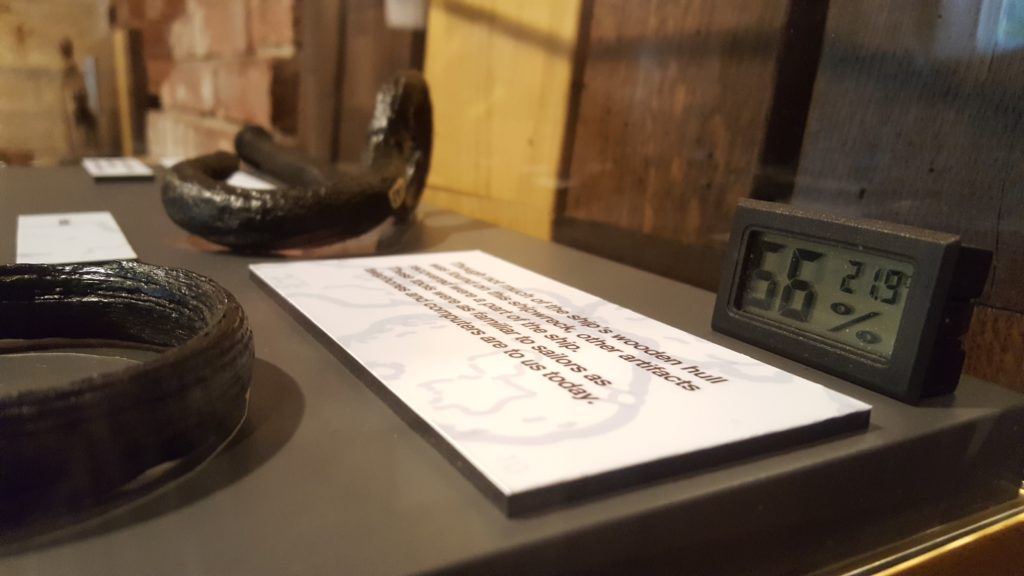

For the artifacts that remain, collections and conservation staff carefully installed them in the Wrecked! exhibit. From here, they need regular check-ups to make sure the conservation worked properly and that no new threats to the objects’ stability have popped up.

Most of the time this only entails checking to make sure the cases are clean, still sealed and not damaged. Obviously, this is to keep the artifacts safe and limit the amount of touching and handling from visitors, which can seriously damage items. Each case also has a small sensor that displays the ambient temperature and humidity inside. Even though most of the artifacts are metal and appear to be solid and stable, slight changes inside the case can lead to new problems.

Still, with all the best efforts of the conservation staff, sometimes things do not go as planned. One artifact in particular needed extra care after it had gone through the normal, expected process. The teakettle currently on display in the basement of the Keeper’s House was put on display prior to the grand opening of the Wrecked! exhibit.

Unfortunately, only a few days later, white spots appeared on the surface of the metal. These spots were where sodium carbonate, the electrolyte in the electrolysis process, had not fully rinsed out of the artifact. Between the rinsing and sealing phases no electrolyte appeared, but almost a week later had worked through the sealant. While not overly detrimental to the artifact’s condition, the excess carbonate showed that the kettle needed to be rinsed once again and then resealed.

So, while artifacts you see on display in museums have undergone a lot of work to get them back to near-original condition and stable for display, there is still more work that goes on behind the scenes to make sure they stay that way.

Andrew Thomson is the Assistant Conservator for the St. Augustine Lighthouse & Maritime Museum. He received his graduate degree and training from the Conservation Research Laboratory at Texas A&M.