Since over two centuries have passed, I guess we can release this sensitive information. At one time it was top secret and valuable to the enemy. This information would have been onboard the ship that LAMP now calls the Storm Wreck. In 1782, when St. Augustine found itself as the recipient of thousands of Loyalist refugees, ships wrecked in our inlet attempting to get to safe harbor. Research continues through the winter, while we plan our dive season, and invariably we come across original documents mined from British and Scottish archives that tell amazing stories. We want to share one of these documents with you now. Fire two guns and show a green pennant at the mast head to keep reading…

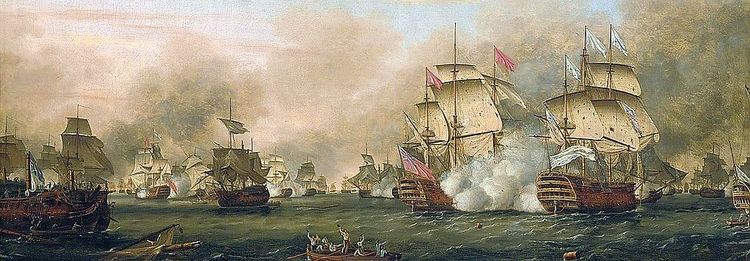

In April of 1782 Admiral George Rodney, commanding the Jamaica Squadron, crushed the French threat to Jamaica at the Battle of the Saintes. His opponent, Adm. Comte de Grasse, sailed mightier and more maneuverable ships yet at the end of an 11 hour battle, surrendered his sword to Rodney. Adm. Comte de Grasse had bottled up the British fleet and beaten them at the Battle of the Chesapeake the previous year, which led to British surrender at Yorktown in 1781. This action at the Saintes was not only a decisive British victory, it was retribution…revenge. Immediately, British men in the dockyards of Kingston breathed easier knowing that the steel of Louis XVI could no longer threaten to pierce their breasts. Rodney was an immediate hero, an angel of the British Caribbean. Upon his return to England, King George III made him a peer of the realm and, for the first time in England, Rodney became a given name for baby boys.

Furious and continuous cannonading reduced British and French ships to splinters over an 11 hour battle. When the smoke cleared Adm. Rodney’s tactics and a favorable shift in the wind amounted to one of the most strategic British victories won in the Caribbean.

Victory at the Saintes spread like wildfire through the fleet. Just as the signal ‘Winston is Back’ would inspire the royal fleet in 1939, Rodney’s achievement was sweet news from a bitter war. Much of his majesty’s fleet was engaged in the dismal conflict of the American rebellion, and by 1782, had lost the war despite having won many battles. In Charleston, South Carolina, Loyalist families and British troops were bottled up, waiting to depart for brighter futures. A huge mass of shipping lay at anchor in the harbor. Like a giant, living conveyor belt, ships filed from their moorings to wharves, took on people, soldiers, and goods, and returned to their moorings to wait. Under the steely gaze of Rebels, Loyalist merchants loaded their goods onto ships flying the Union Jack.

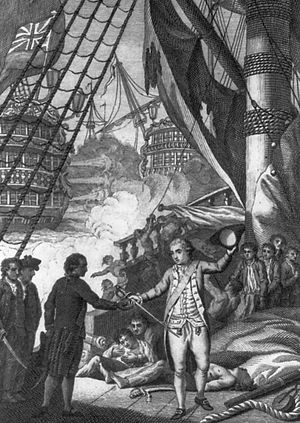

French Adm. Comte de Grasse surrenders after the Battle of the Saintes.

With the last civilians aboard, British military forces in the city followed suit. Muffled drumbeats gave cadence to the Army’s withdrawal and not long after, a chorus of sailor’s voices brawled out the news that a 120 capstans were weighing 120 anchors. Sharp calls of sailing masters issued commands to let go topsails and, from the Battery to Shutes Folly, acres of canvas appeared with a dull roar. Those whose duty it was to sail the ships looked to sea, all others looked to land and watched their former homes draw father away.

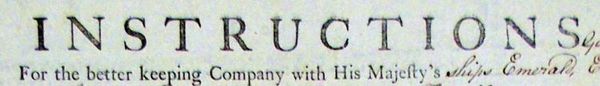

On board each ship, captains carried a copy of convoy instructions passed out by naval dispatch. In it, every situation was planned for, and a response prescribed. On page two of the “Instructions For the Better Keeping Company with His Majesty’s Ships” there was a blank space following the words “In Case we should lose Company, and meet again, he who Hail first shall ask, What ship’s that?, then he that is hailed shall answer…”

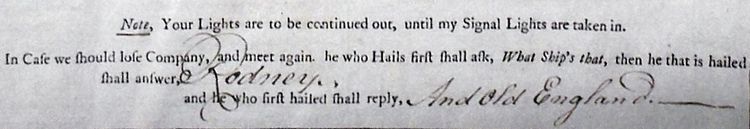

In this blank space, Captain William Nell, commander of the convoy sailing from Charleston to Jamaica penned the single word “Rodney”. The Instructions continue, “and he who first hailed shall reply…”. Capt. Nell inserted “And Old England.”

As a merchant under convoy you sailed under the protection of the Royal Navy. The American Revolution was not officially over and Rebel privateers had valid letters-of-marque licensing them to plunder and destroy Loyalist shipping. Like a flock of sheep who have smelled a wolf on the wind, the convoy was skittish and darting. The royal navy provided the ships Emerald, Endymion, Belisarius and the sloops Magicienne and Hornet to shepherd the convoy to safety. The destination for many of the ships was Port Royal, Jamaica, for some St. Augustine in East Florida, and a few ships were consigned to full fathoms five. It can be assuredly said that the sign and countersign proscribed by Capt. Nell had a comforting sound to it, reassurance to Britishers whose world had come apart.

Passwords like this were often known as a ‘sign’ and ‘countersign’, a way of distinguishing friend from foe. I challenge, you answer ‘Rodney’, and I respond ‘And Old England’. As simple as that. Imagine a dark night and you are on watch, suddenly the sound of waves washing past the hull is doubled and out of the gloom comes a darker form, another ship. In 1782 it could have easily been a Rebel raider, with guns loaded to take you as a prize. Calling out the signs, there must have been some captains who had to muster their strength and not let nervousness crack their voice. Hearing the words ‘Rodney’ from another ship set all of this at ease. Ships in convoy carried no lights at night unless specifically making or answering signals to and from the commodore. During gales and moonless nights it would have been easy for a ship having problems to be left behind, only discovered at sunrise by a gap in the line. Fumbling back into the convoy at night, the only thing that prevented one of the escorts from blowing you out of the water were these words.

An excerpt from the Instructions stating the sign and countersign. This was top secret in 1782.

The Instructions were indeed very useful. In pre-radio days signals were made by flags, cannon fire, and candles. With myriad circumstances, ships found themselves in due to weather, enemy, and breakdown, great specificity was outlined in Capt. Nell’s Instructions and everything from ships leaking water to being overwhelmed by a superior enemy force was covered. Of course, we know what happens to the best laid plans. From the lieutenant’s log of HMS Belisarius we know that she was constantly signaling to ships to catch up, rejoin their station, or somehow shape-up. We also know that the Royal Navy exerted real effort to chase down and destroy Rebel privateers and challenge approaching sails to distinguish friend from foe. By the time the convoy reached St. Augustine, it had become ragged around the edges. Ships were leaking, some had sunk, and some few captains broke rank to fend for themselves. No matter what the calamity, purpose, or circumstance though, the words ‘Rodney and Old England’ were on every captain’s tongue. It was, when staring into the muzzle of a loaded cannon, the secret code that saved your Loyalist hide.

The Lighthouse and LAMP cannot operate without our volunteers. From painting to conservation to research, they are the right arm of our institution. This document was brought to our attention through the archival work of Dr. Lillian Azevedo. She painstakingly combed through the Public Records Office in London as well as the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich, England this past January to find doucments that help us understand the history of the Storm Wreck. To her, and each of our volunteers, we owe a continual debt of gratitude. Thank you.

CLICK HERE TO LEARN MORE ABOUT THE STORM WRECK AND LAMP!

This shipwreck is brought to you by the St. Augustine Lighthouse & Museum, and readers like you! Get involved and help support maritime archaeology in the Nation’s Oldest Port! Click HERE to learn how you can help.