Field School student Katie Kelly, of the University of Indianapolis, enters the water with a giant stride, to participate in the excavation of the 18th century Storm Wreck. Katie was presented with the 2010 David Switzer Young Pioneer Award, which is awarded to the field school student who best exemplifies the qualities of hard work, dedication, and teamwork.

This is the final installment of a three-part blog focusing on our 2010 summer field school activities. As usual, it has been very busy here during the post-fieldwork season, so its been a while before I’ve had a chance to get back and re-visit those great memories from the summer’s fieldwork.

Part I of this blog focused on the initial training of our 2010 field school students, including intense zero-visibility diving training in the pool, and also on the initial preparatory work on the site of the Storm Wreck, an 18th century shipwreck discovered during the previous year’s field school. Part II focused on the diving investigation of the Bayfront Ballast Pile, a site located in the harbor off St. Augustine’s waterfront. We had switched focus to that site when we were faced with mechanical problems with our primary research vessel, Roper. Once the Roper was fully repaired, courtesy of Ring Power Marine Services, we were ready to return to the offshore ocean environment, to begin excavations on the Storm Wreck. After being away from this colonial period wrecksite for a week, excitement has built, and we are all eager to begin excavations and make discoveries . . .

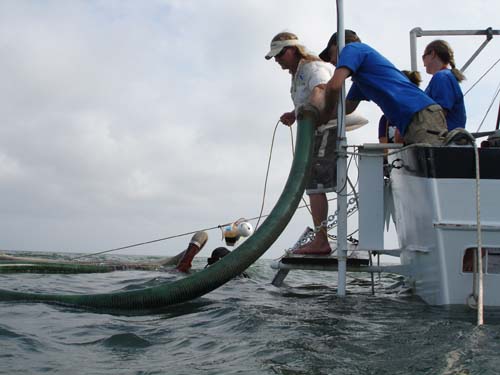

LAMP archaeologists Chuck Meide and Brendan Burke hand off the dredge hose to a field school student diver in the water, preparing for excavations on the 18th century Storm Wreck.

Before we had to temporarily suspend our operations on this site, we had prepared for excavation by completing a magnetic survey of the area, and by establishing a grid system over the spot where we calculated the iron cauldron lay buried beneath the sand. The next step is to secure some fifty feet of dredge hose on the bottom. The hose is somewhat heavy and awkward, especially out of the water, so this is a task easier said than done.

On the deck of the boat, a gasoline-powered water pump is used to force water through a firehose down into the dredge head, which creates the suction effect allowing divers to suck up sediments from their excavation unit. The water pump is seen here, next to field school student Mike Jasper. Mike was our only high school student participating in the field school this year. At the time he was freshly graduated from a local school, Nease High, and at the time of this writing he has completed his first semester at Georgia Tech, studying to become an engineer. We can attest to his engineering skills, as he was always able to get our pumps and other engines operational in the challenging marine environment.

Here Mike and Chris Borlas, a 2009 field school student who has returned to work as a Field School Supervisor, test the water pump to make sure it is operational before sending divers down to begin excavation.

Typically our working divers are tethered to the boat, and fed breathing air, by the use of hookah hoses. The coiled yellow hose provides air to the divers from a gasoline-powered compressor on the deck of our vessel. Here field school student Devin O’Meara of Grand Valley State University of Michigan uncoils the hookah hose in order to deploy it for divers.

Once the hoses are uncoiled, unkinked, and blown free of any debris, they are handed off to the divers. Our divers use the hookah as their primary breathing source, but they wear a full scuba tank on their backs as a backup system, in case the hookah runs out of fuel or fails for any reason.

On the bottom, the divers use the dredge intake hose to gently vacuum up sand from within the 1 m by 1 m excavation unit. We have laid out a total of six units on the seafloor, and plan to excavate this six square meter area by the end of the summer. The edge of the excavation grid can be seen on the left, made from white PVC pipe marked every ten centimeters with 10-cm long black sections. The yellow line adjacent to the PVC secures it to the seafloor. The diver is carefully fanning sediments into the sucking dredge hose using his bare hand. The diver takes care not to accidentally suck up any artifacts exposed during the digging. Artifacts are mapped in place, photographed if possible, and then recovered by hand.

The sand and shells and everything else sucked up the dredge is filtered through a doubled-up mesh bag at the end of the dredge hose exhaust. This results in a large amount of spoil, in the form of shell hash, that is recovered at the dive’s end and brought up to the surface for sorting. Here field school students sort through buckets of dredge spoil, hoping to find small artifacts that the divers may have accidentally sucked up the dredge. Not a single find, no matter how small, is missed.

All such laboratory work, including sorting for artifacts and the actual stabilization treatment processes that artifacts will be subjected to, is overseen by LAMP’s new Archaeological Conservator, Starr Cox. Starr is seen here on the research vessel. In addition to being an expert on the conservation of waterlogged artifacts, Starr is a diving archaeologist and participates in the ongoing fieldwork.

On this day, we are paid a visit by the Chair of the LAMP and Lighthouse Board, retired Major General Gerry Maloney (U.S. Air Force). He assures us that we have passed inspection with flying colors! Here is Gerry flanked by LAMP Director of Archaeology Dr. Sam Turner, and field school student Katie Kelly.

The site also provides a rare treat for our students–a chance to swim with wild dolphins! Dolphins are regular visitors to our shipwreck sites, but these have come in particularly close to the boat, and our divers underwater can easily hear them clicking away in dolphinspeak. If only we had built-in sonar to see through the dark murkey waters!

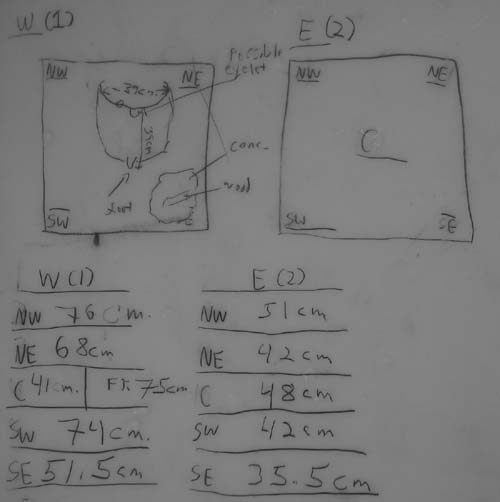

In the meanwhile, excavators have uncovered the cast-iron cauldron in Unit 2, right where we expected it to be located. Sam draws a rough sketch of the cauldron and an adjacent concretion once they are fully exposed. The numbers in this sketch map indicate vertical depths pr elevations in centimeters. Our excavators record the starting and ending elevation of each corner of the unit, and its center, before starting and after finishing excavation. Later divers will return to this unit and make a more detailed, scaled drawing of the objects later, hopefully when visibility improves.

Here is an image of a diver inspecting the cauldron once it was rigged for lifting. Unfortunately, by the time we were ready to raise the cauldron from the bottom, field school was over. Some of our field school and high school students, however, stayed on as volunteers and got to participate on this exciting day, which we blogged about here and here.

In addition to the large iron cauldron, which was the first historic artifact discovered on this site, three other iron cauldrons, all of different, smaller sizes, were uncovered during the excavations started during field school. Above is a medium-sized cauldron, which has a smaller cauldron nested inside it.

Here is a view of the upper portion of this double-cauldron. The smaller specimen’s rim can be seen inside the rim of the larger cauldron.

A number of small finds were made during and in the two months after field school. At top on the left is the base of a wine glass, which dates to the 18th century. At top right is a brass buckle, perhaps from a belt, strap, or shoe. At bottom is a small sample of lead shot. These tiny pellets were used as birdshot, though they could have had a military application as well. These shot are all mishapen and varying in size, and often feature a small dimple. This indicates they were made by the Rupert process, a manufacturing technique first publicized by Prince Rupert of England in a book he published in 1665. Molten lead was poured through a bronze colander, and the tiny droplets fell into a bucket of water where they cooled in the distinctive shape seen here. They began to fall out of favor starting in 1769, when a new process was invented which resulted in perfectly round shot.

Our most excited find made during the summer of 2010 was something that we didn’t even realize we had until October. In July, shortly after the completion of field school, an iron concretion was recovered from the seafloor, one of perhaps 30 found on the wreck. Once it was cat-scanned at Flagler Hospital three months later, we realized that it held an encrusted flintlock pistol! We have blogged about the pistol here, here, and here.

The Class of 2010!

All in all, this was a great field school and a great shipwreck. As I write this last installment of our 2010 field school blog (better late than never!), we are beginning to advertise for next year’s field school, what promises to be another very exciting season. We are hoping to have some of our experienced students from last year return as supervisors, and to welcome a new group of participants to help us excavate this fascinating shipwreck, and learn the basics of underwater archaeology while doing so.

Happy New Year everyone! May we have even greater discoveries in 2011!