A sulking schooner fell in with the British blockading squadron during December of 1813. Biting wind and freezing spray calloused a sunwashed seascape. Harsh winter light cast stark lines across the sleek vessel making her appear even sharper than she already was. Lieutenant Murray gently tacked the Mosquidobit and kept communication flowing up and down the line of British schooners, sloops, and frigates. Today things were quiet. Hardly a word was passed on deck to maintain the evolutions. No new sails, no news, nothing to do but pace the ship within its assigned box. Back and forth, back and forth, flags hoisted up, fluttered down, log kept, deck swept. Piercing cold wind kept Lt. Murray’s gaze down to clear wind tears from his eyes and thoughts wandered to this recently built ship, one of the fastest in the squadron and once a proud privateer known as Lynx. Only a few months prior, she had fallen into British hands at the mouth of the Rappahannock River and ended her role as a patriot combatant.

Lynx‘s wheel.

Only a year and a half prior, during a humid Chesapeake July, a 225 ton schooner slipped into the water at Fells Point, Maryland. Thomas Kemp’s men had crafted oak and pine into a ship that would take forty men to sail and could outsail and outhandle just about everything else afloat. Lynx’s investors were motivated by the clouds of war and put together a speedy ship to have it available for privateering. The US naval force was still in its nascent stage and needed all the help it could get. A civilian force, sailing under letter of marque, had been authorized to seize and harass British shipping. In order to fight what Thomas Jefferson would call the “War of Independence” ships like the Lynx were pouring out of builder’s yards and the ink on their letters had hardly dried when they were cruising the east coast and snapping up prizes. Dangerous and daring, privateering was often highly lucrative and spurred a generous growth in domestic shipping tonnage. The war afloat would largely be fought by merchantmen and by 1815 over five hundred privateers had lent their service to gain true and lasting independence.

Lynx resting at dock.

Lynx was a steed among a stable of thoroughbreds. Baltimore clippers were fast ships built with swept, romantic sailing rigs that could carry a light armament just as handily as a precious cargo of valuable French perfumes and silks. Their value was in their speedy ability to race about the ocean, taking and evading as necessary. Beyond the War of 1812, Baltimore clippers saw use in the slave trade. An infamous clipper, the Echo, was caught slaving and would later become the Jefferson Davis, ultimately wrecking in St. Augustine during the summer of 1861.

Even southerly St. Augustine was directly impacted by privateers during the War of 1812. A second, illicit war was being raged in Florida in 1812 which would become known as the Patriot’s War. Fernandina was occupied and declared to be US sovereign territory. Skirmishes erupted throughout the peninsula and Florida was on the brink of falling into total disarray. Privateers from the Chesapeake were attracted by the smell of blood and money and coursed southward to the Atlantic bight in a brief and legally-tenuous blockading action. Two privateers, the Nonesuch and the Hornet, shook Spanish dominion of the sea lanes around St. Augustine as they raided the cargo of the Eugenia, Dos Hermanos, and briefly captured the city’s guard ship, the frigate Pizarro. Fortunately for the Spanish colonists, the letters of marque held by the Nonesuch and Hornet were not valid to take Spanish flagged shipping as prizes and so each ship was released. But the point was made, American forces owned the Atlantic around north Florida. The Nonesuch, flagged out of Norfolk, Virginia was one of the ‘infernal Yankee skimming-dishes’ (USMM 2002) built by Baltimore yards and at 145 tons was a little smaller than the original Lynx.

A bronze lynx head in the main salon.

This brings us to the ‘infernal Yankee skimming-dish’ in our own harbor. As many of our readers know, the Privateer Lynx has decided to call St. Augustine her winter home this year. After a grand arrival (Read the arrival blog here) her routine has settled down into a maintenance workup. Sailing wooden tallships incurs an impressive repair and maintenance bill and so, from time to time, operations come to a slowdown so work can take place.

Replacing bungs in the decking, re-varnishing and finishing woodwork, and a thousand other tasks become the daily routine for the boat’s compliment. The lazarette is opened and from it the bosun administers tar, glue, replacement fasteners, paint, small stuff, and other sundries of wooden ship life. This may seem like a mundane life compared to dashing through blue water with a reef freshly shaken out and a seaway gurgling through leeward scuppers but is necessary to keep the boat safely sailing and in her prime. It is this period too, that a crew can get to know their vessel in the most intimate ways. Climbing down into what could generously be called a ‘confined space’ to check the lip seals on the variable pitch propeller shafting may not have the glory of firing a carronade but the process forges an acquaintance that is required from a solid ship’s company. Spending hours re-wrapping, or ‘serving’, standing rigging may seem like cruel and unusual punishment but it requires hours of staring to nurture the familiarity that only time can foster.

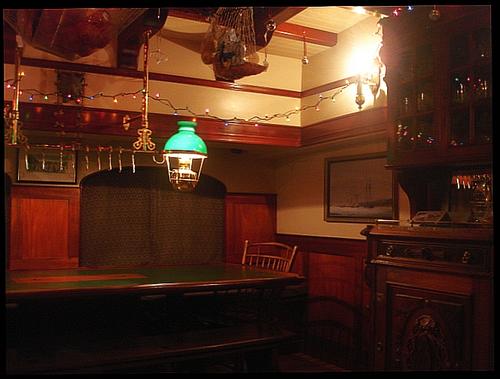

And so during this re-work phase, Cpt. LeeAnne Gordon invited me on board to meet the crew and tour the boat. I had been on board previously but this time I was armed with a camera and a scant familiarity of my surroundings. My first time belowdecks was for Lynx’s Christmas party. On a cold and blustery Winter evening we had comfortably sat belowdecks to enjoy the wooden warmth of Lynx’s main salon. Matt Mills, ship’s cook, had prepared a hearty meal for us and plenty of appetizers went round the table to keep us appropriately stuffed. For the festive occasion a little rum and eggnog was shared to knock the edge off. With each Alberta blast, the bare rigging howled in protest and Lynx took a subtle roll, shaking off the assault. The exquisite beauty of the salon and warmth of the mahogany, brass, and leather added to the special occasion and the lubber in me was particularly jealous of these posh surroundings.

But I will depart the Christmas Party and the salon for this afternoon and let me lead you on the tour so kindly offered by Cpt. Gordon. I arrived a little before sunset to enjoy the afternoon light and Lynx was sitting pretty, as usual, flying her colors. I noticed too, that on the ship’s starboard halyard the US Lighthouse Service pennant was flying. While the USLHS pennant hasn’t flown over a government vessel since 1939 we like to present our maritime friends with a pennant symbolizing our mutual interest and common goal.

The USLHS pennant flying proudly.

Pennant aside, I climbed aboard and began my tour aft at the wheel. The ship’s steering gear is a little more sophisticated than an original 1812 privateer. Lynx’s bronze and teak wheel are nonetheless gorgeous and connect to the rudder via a leadscrew and sector gearing. This system eliminates lash from the rudder and is no new system in itself. The foundry in Lunenburg, Nova Scotia who cast the steering gear has cast this gear since 1891. Lynx’s binnacle, or compass, is well surrounded by protective wood, but with a hinged glass top by which the helmsman can steer. On the davits, Lynx carries a ship’s boat not unlike that being built at the LAMP Boatworks. In the days of privateering, this launch would have carried the proud prize crew to the catch of the day and often acted as a sentry boat ahead of the ship to sound a channel, locate a reef, or bring provisions aboard. Cpt. Gordon mentioned the possibility of taking the ship’s boat out for a sail one weekend, something I hope to see!

Strong stuff stored in here, the ship’s powder locker.

A 6lb carronade, one of four on deck.

One of the swivel guns.

I noticed in the starboard quarter a locker with ‘Explosives’ painted on it. Lynx’s guns do fire and so her store of powder is carried here. During days of earnest conflict, where gunfire as often signaled a naval duel as salute, powder was carried belowdecks in an protected locker where it could be kept dry, secure, and out of harm’s way until needed. Moving forward along the starboard rail we come to one of the ship’s four swivel guns. If you have visited the Lighthouse Museum, then you may remember the swivel gun recovered from the sloop Industry, a 1764 wreck offshore St. Augustine. Lynx’s swivel guns are very similar and, like the originals, can be quickly loaded and trained to pacify the decks of an unwilling prize. To back up the little bark of the swivel guns, Lynx carries a compliment of four carronades. These short, businesslike guns harken back to 1770 when it was discovered that short range blasting guns, able to throw a heavy projectile with great smashing force often outweighed having heavier, longer cannon. Many privateers also carried one or two pivot guns, cannon mounted on a trackway and able to spin in 360 degrees. The longer range of these guns often acted as a ‘greeting’ and persuaded the victim to haul sail and heave-to. Lynx’s guns are fully operational and last heard during the Regatta of Lights when she saluted the city and regatta guests. After touring this far we began to move forward and the gauntlet was thrown down. “Do you want to go aloft?” Cpt. Gordon asked.

“Yes” I answered.

“The foremast or the mainmast?” she asked

“Which one is cooler?” I blundered.

“The foremast is.”

“So it is, lets go!”

I grabbed a harness from the bosun’s locker and strapped in. After feeling like a complete goober for trying to wear the harness around my waist and legs (I should have known better since I’ve worn the things but apparently the moment seized me and subdued logic) I began my ascent up the starboard shrouds. My climb was not the sprint of a jack tar, but the stunted grabble of a landsman. Nontheless, I was successfully gaining altitude and Lynx grew smaller. From the docks, the height of the foremast does not appear to be approximately one-mile high but once up to the yards, I seemed to detect lesser amounts of oxygen. It was at that precise moment that I remembered among my toolkit of fears, heights is low down on the list, but present. Fortunately the reality of the moment and lust for the experience took over and I managed to stand in the completely still upperworks and gaze out over our fair city. This time I did not ‘lay out’ on a yard, which means to climb out on the footropes hanging under the boom and lean over onto the boom for sailhandling, but will save that for my next venture aloft as I will see to it that the exhilaration of being aloft in a tallship undoubtedly outweighs any measly quirkitude of heights. In other words, I just need to find my inner squirrel.

Cpt. LeeAnne Gordon supervising my ascent.

A view from aloft.

Our lighthouse from Lynx‘s rig.

Down to the deck.

After the excitement aloft, I resumed a more benign altitude and moved forward on deck. Lynx’s bell, cast out of ‘bell metal’, a beautiful bronze-like copper alloy, is affixed to the foremast and has the ship’s name cast into it. During the days of the original Lynx, a ship’s bell would often be used to strike the watches as well as sound out during times of fog. Just forward of the bell is the entrance to the fo’c’sle which traditionally serves as crew quarters. Down a steep companionway are berths on either side of the ship which the ship’s company calls home. Anyone familiar with Richard Henry Dana’s “Two Years Before the Mast” will know that the fo’c’sle is traditionally stationed in this part of the ship. Forward of the foremast, this is the wildest and sometimes wettest place to reside. While in their berths, the crew can literally hear the water passing over the hull, be it a smooth lapping from a bluebird day or the coarse and untimely beatings of a gale. This is also the only place in the ship that a captain cannot roam without permission from the crew. A courtesy of the sea, a crewman can expect to find scant privacy only here.

Back on deck I am invited to the main salon by enticing wafts from the Charlie Noble (a fancy word for saying ‘stove chimney’) and open salon hatch. The ship’s dinner is about to be served and I’ve been invited to join the crew. The evening victuals are cheeseburgers and coleslaw, expertly prepared by Matt Mills, ship’s cook. Inside an area about the size of a walk-in closet, only more cramped, Matt performs his magic. To sample this life, just take half of your kitchen, throw it away, put the remaining half into a minivan, and then have someone rock it back and forth while trying to fry an egg. Since we were in harbor everything was dutifully staying put but imagine a good rolling sea swishing the soup around precariously in its pot! In heavy weather, Matt’s job is further complicated by the fact that appetites may come and go with the mal de mer, and thus the ration sizes will change accordingly.

The main salon.

Eating cheeseburgers on tallships is something I rarely do but eating a cheeseburger in the salon of an 1812 privateer on top of a priceless mahogany table was a first for me. The main salon of Lynx is a work of art. Paneled in mahogany and maple, the cabin reeks of splendor and grace. The original Lynx would have had no such thing. Built fast and thriftily, opulence had little place in the first wave of 1812 Baltimore clippers. But here, this opulence celebrates the victory these ships achieved for our country and is not out of place. On the bulkheads are placed etchings of other famous 1812 naval scenes and the ship’s launching plaque, bequeathing good fortune and fair seas to all who sail aboard her.

I left the main salon to visit the engine room and machinery space. Lynx may be a 19th century ship but she has to meet 21st century expectations to some degree. Part of this means she has to stay on schedule and being a week late because you were becalmed in the horse latitudes doesn’t carry the meaning it once did. Similarly, the ship can use her engine to maneuver out of dangerous situations and traverse waterways, such as canals and locks, that don’t lend themselves to sailing. Powering Lynx is a Caterpillar 3306B diesel engine churning out 290 horsepower. To put the power in the water, a Hundested variable pitch propeller is controlled from deck and can be feathered when sailing to minimize drag. The space is clean and well-organized the big yellow Caterpillar is flanked by two Northern Lights generators, which power the ship’s electronics when underway. Propeller control, dewatering pumps, lube oil, electronic distribution panels, and tools all call this space home. Managing the compartment is Dylan Leach, the ship’s engineer.

Lynx‘s aft cabin. Not too shabby!

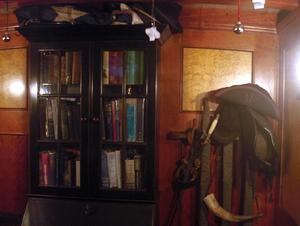

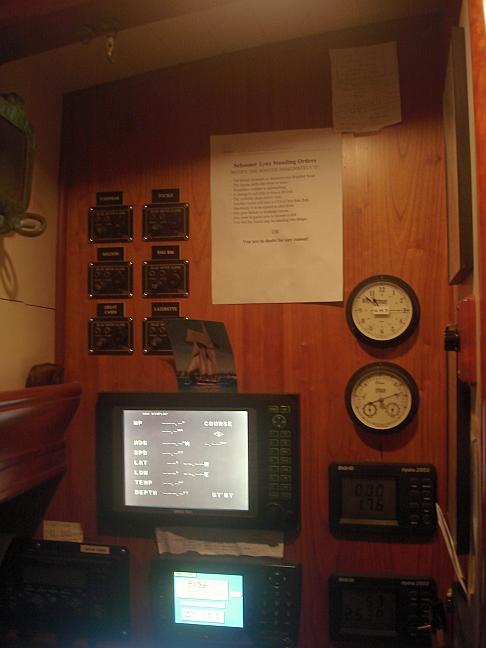

The next space I visited rivaled the main salon in beauty. The after cabin is home to the ship’s navigational station, instrumentation, flag locker, library, small arms, and officers berthing. After descending the salon ladder the after, port quarter of the space is occupied by the flag locker. Signal flags, national colors, and honorary pennants get stored here, for deployment to halyards. When Lynx leaves St. Augustine, the pennant of the US Lighthouse Service will join this locker as a memento from the St. Augustine Lighthouse and Museum. Forward of the locker is the nav station, where everything from the ship’s barometer to chart plotter are mounted. When underway the captain spends many hours here, checking communication with shore, monitoring the weather, watching the radar, and updating the ship’s plotted position. Next forward is a small cabin for the ship’s chief mate, small and confined but enough to make do. The forward bulkhead in the after cabin has a bookcase attached to it, the ship’s library. Host to a rabble of famous authors, it is here that crew and visitors may read about Baltimore clippers, the War of 1812, and other traditional seagoing tomes. Snugged between the bookcase and starboard bulkhead is the ship’s collection of smallarms. Cutlasses, pistols, muskets, and accoutrements of combat rest here along with what is cordially called the ‘Taco Hat’. Command of a ship in 1812 not only brought great responsibility but great headgear. Known as a bicorn, as opposed to a tricorn, these chapeau naval were de rigueur among the command afloat. Cpt. Gordon let me try the taco hat on for size, and its harsh contrast against my overalls was a stark reminder of my status as landsman, nay lubber. The starboard side of the compartment is made up of two more cabins, one for the captain, and one for the bosun. Similar to the mate’s cabin, they are small, sparse, but serviceable. For the ease of the occupants, a head, or bathroom, is built into the after-bulkhead. Quite literally a water closet, the head is complimented with tilework, mahogany, and stainless fittings. A small stove sits outside the head to heat the compartment during cold weather and is surrounded by beautiful brass piping to keep burns to a minimum!

A place to read, or arm yourself for a fight.

The nav station.

Returning to deck, my tour was complete. While I had absorbed much from the tour, much is left to be known about Lynx. A sailing vessel like this requires years at sea of handling in good weather and foul to fully get to know it. To feel her handle underfoot, to eye the rig and know where tension and force can be most efficiently applied, to keep together this little world of wood and men takes a professional mariner. Sitting still at the dock, Lynx appears graceful but her true beauty and style emanates from her sailing form. Striding across Atlantic rollers with full sail set the imagination isn’t pressed hard to picture an original 1812 privateer hunting British prizes. If you get a chance, take a trip down to the municipal marina to see Lynx, a tribute to our War for Independence and a proud maritime past. Check out too, her ship’s boat, which is now at the St. Augustine Lighthouse and Museum undergoing refurbishing and repair at the LAMP Boatworks.

The pin rail. Each one of these stout wooden ‘pins’, called belaying pins, holds a line. Each line has a name and lives on a specific pin. This is one of the control points for the ship’s sails.

Flag locker.

A view from the headrig. Imagine a good rolling sea underfoot.

The cabin sole has been redone since this photo was taken, and looks beautiful!

On deck.

The Lynx’s Christmas party. (Photo courtesy of Elizabeth Foretek)