It all started with a phone call on Tuesday May 29 from the Jacksonville newspaper, the Florida Times-Union, asking for a comment on the discovery on Vilano Beach. The find was a partially intact chainplate assembly, part of the rigging hardware, from what appears to have been a 19th century shipwreck in the vicinity.

We hadn’t yet heard about the find, which had been made just a day or two earlier by former LAMP Director Billy Ray Morris as he was out surfing. We quickly realized that it was historically significant and in danger of damage or theft by looters. After a call to Billy Ray, who shared the information he had gathered with us, Sam and I set out for a look ourselves.

On route we met up with one of our most valuable volunteers, Tim Jackson. Tim lives in the immediate area and we invited him to tag along. With Billy Ray’s directions it was easy to locate the wreckage. It took only a glance to confirm Billy Ray’s identification of the objects as part of the chaining plate assembly.

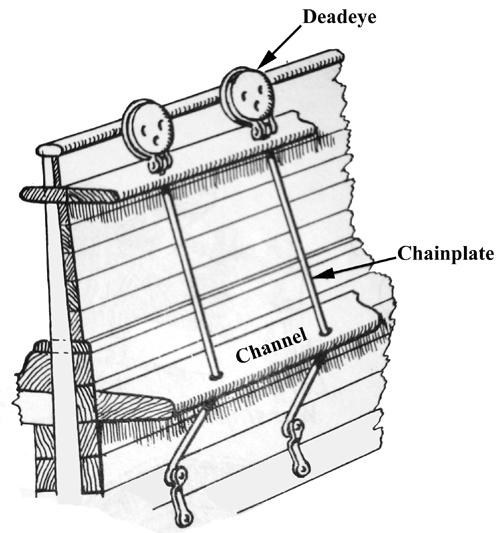

Here is a close-up of the wooden deadeye, which is encircled by the iron strap known as the chainplate. Deadeyes were round, flattish blocks of hardwood—often elm or lignum vitae—pierced with three holes. These holes made them look somewhat like skulls; hence their macabre name.

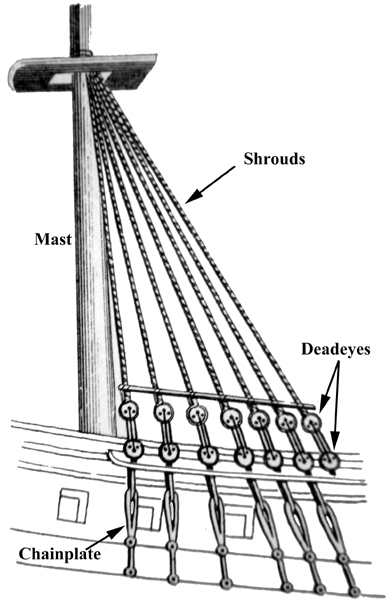

The chainplates and deadeyes were part of the standing rigging of a sailing ship. These were for attaching the lower ends of the shrouds to the side of the ship, and for tightening the shrouds. The shrouds were the ropes that steadied the masts and held them tightly into place, and also allowed easy access for sailors to climb up to the mast tops. When we picture a pirate ship, the shrouds are the spiderweb-looking ropes, or net-like ropes, stretching from the tops of the masts down to the sides of the ship. Here is an 1819 diagram of a ship’s side and mast, showing the location of the mast, shrouds, deadeyes, and chainplates.

The ropes of the shrouds went through the holes in the deadeyes. This way they could be periodically tightened without letting up the strain on the masts.

Here is another diagram of a 19th century ship’s chaining plate assembly:

Here is an actual 19th century ship’s chainplate assembly–this is a picture I took of the USS Constellation, built in 1854 and still afloat in Baltimore.

And here is an earlier version of the standing rigging components, from a model of the English 90-gun warship St. George, built in 1701. This model is on display at the Annapolis Naval Academy.

The wreckage on Vilano Beach consists of an entire intact chainplate, complete with deadeye. Also there is a significant fragment of the lower part of a second chainplate. The bolts which were driven through the hull are also intact, which will give us a good estimate of the thickness of the hull at this point (allowing for an estimate of the ship’s size).

Billy Ray meets us on the beach and tells us that these pieces have been moved from their original location by beachcombers, and that some other pieces he had witnessed are now missing. While the chainplate is heavy, maybe around 100 lbs, it is still portable, and it is likely that someone simply picked up and walked off with this piece of history. This is unfortunate, as it will probably end up in someone’s garage where it will likely rot away into a pile of rusty fragments.

Billy Ray also tells us that more components are still in the sand, but hidden by the waves because it is high tide at the moment.

In hopes of saving these exposed artifacts, we call Dr. Roger Smith, the state underwater archaeologist. Upon hearing the situation, he gives us verbal permission to recover the artifacts and store them in a vat of water at LAMP’s headquarters, where they will eventually be stabilized by our conservator, Kathleen McCormick.

Recovery is simple enough–we simply pick up the artifacts and walk them down the beach to the nearest beach access point. They get pretty heavy and our arms are tired by the time we finally load them into the car.

Once back at LAMP headquarters, we store the artifacts in our secure outside conservation area, covered in wet rags. The storage and treatment vat is much too heavy for just two of us to move. First thing tomorrow morning we will prepare the vat to ensure they remain wet.

This turns out to be a complex process involving lots of people, but it is actually a pretty exciting morning. We’ve got the Lighthouse maintenance workers (Rich Mikola, Ray Caron, and Heather Puhl), the education guys (Andy Magee and Jeff Wessel), our PR coordinator Beau Phillips, our conservator Kathleen McCormick, and Sam and I all working together to make it happen. The first step is to partially disassemble the fence in order to make room for the vat’s removal.

Meanwhile, Beau makes sure that the chainplate stays watered down and in the shade. Drying out can irreversibly damage both the wooden and iron components of this artefact.

Next step—heave, ho, we all lift the vat, and muscle it out of the enclosure and onto a small trailer behind our little tractor. The back of the vat rests on a small hand-pulled cart. Its not pretty, but we think it’ll get the job done.

The next step is to prep the ground where this vat is going to be placed. It will be sitting on cement footers supporting two 2 by 4’s, and this entire assembly will be placed right in front of the Keeper’s House, right by the Lighthouse. This way a maximum amount of visitors will be able to see the artifacts, and view the entire conservation procedure. This is an important part of our public archaeology mission.

Then, slowly and carefully, we ease the vat forward using the tractor to pull it and the hand-cart to support its rear. I won’t tell you how many times it fell off, but in the end we got it there safe and sound.

Almost done . . . again it takes teamwork and muscle-power to lift the vat up, set it down, roll it right-side-up and into place.

Job well done!

We finish the vat preparation just in time. Beau has been doing his public relations job well, and we have reporters from the local newspaper, the St. Augustine Record, as well as from Channel 12 First Coast News. Again, this kind of public outreach is part of our mission, and an important component of public archaeology. What plays in our favor is that shipwrecks are exciting to most folks, so its easy to get the press interested. The end result is education for the public, conveying the message that archaeology and maritime history are not only interesting but relevant and important parts of our heritage.

In this picture, I show First Coast News reporter Jessica Clark how the chainplate would have attached to the hull in its upright position. This is a good view of the size of this artifact, as I am just about 6 feet tall.

They film their interview with the Lighthouse in the background.

Now its time for Sam and I to carefully carry the artifact past the Keeper’s House to its resting place in our storage vat.

By the time we get there, a crowd has gathered. Looks like our plan of attracting attention by placing the vat in front of the tower worked. This is one of many school groups that come to the Lighthouse on a regular basis, and they want to know what’s going on. Another great public archaeology opportunity! When I explain what shrouds are using Captain Jack Sparrow’s pirate ship as an example, everyone knows what I’m talking about.

So we have quite an audience by the time we finally get the artifact into its water. We have also added a rust inhibitor (sodium carbonate) to the water, to prevent further oxidation.

One final job in this busy but exciting day, and this is the best part. We get to go to the beach! Since Billy Ray told us about more wreckage that should be exposed during low tide, we have planned a trip back to the scene of the crime at 2:00 pm, when the tide is out its furthest. So we follow the Channel 12 news van, with the Record reporters in tow.

We are joined by several other professional archaeologists from local governmental organizations. This includes Marty Healy, Coastal Training Program Coordinator for the Guana-Tolomato-Matanzas National Estuarine Research Reserve (pictured above at left) and Robin Moore, the Historic Resources Specialist for St. Johns County (below, on the right with Sam Turner of LAMP).

We don’t see anything exposed on the beach, which is a bad sign. It is very possible that someone has made off with these pieces, as we know someone has stolen at least one other piece of the chainplate assembly. We decide to do a quick walking survey in the surf zone, in case there are more pieces hidden by the waves, just out of sight. This is a simple procedure; we simply position ourselves in a line extending from the sand into the surf, spaced just a few feet apart, and walk parallel with the beach for a few hundred feet or so. We’ll stub our toes on anything as large as the chainplate that was recovered.

But, no more luck today. The artifacts are either re-buried, or have been taken by beachcombers. You have to be quick on these beaches if you want to beat the looters. We know that one brass bolt or fastener has also disappeared. But the good news is that we have one entire chainplate intact, which will make a great museum display and provide us clues as to the nature and size of the vessel that shipwrecked here over a century ago.

All in all, just another exciting day working for LAMP, promoting public archaeology, and preserving history here on Florida’s First Coast!

To see the online video of the First Coast News clip, click the link below:

http://www.firstcoastnews.com/news/local/news-article.aspx?storyid=83100

To read the article that appeared in the St. Augustine Record, click the link below:

http://staugustine.com/stories/053107/news_4628148.shtml

Channel Four News also did a story on this–if anyone finds the video online, please post a comment and tell us where to find it.