Pearl Harbor Day’s annual remembrance on Dec. 7 generally sends me searching for images from that horrible attack. Visiting the Pearl Harbor Naval Memorial in Hawaii some years ago was one of the most memorable moments of my life, as I gazed down at the hull of the U.S.S. Arizona, trying to imagine what it was like years before. I remember sitting outside by the harbor and listening intently to stories about that day from two Navy veteran survivors of the attack as smoke rose some distance behind them from burning sugarcane fields. Simultaneously, a small plane flew overhead and, added to the stories, which all worked together to take me back in time to have a glimpse into our nation’s past.

One image that I came across this year was of the U.S. Navy launches tending the U.S. Pacific Fleet’s burning wrecks on that day. These humble boats share a long and distinguished history with other workboats back through time. Large vessels have always required smaller boats to transport people and supplies back and forth between vessel and shore. The evolution of these “ship’s boats” has been long, and they have earned their place among some of the most significant vessels in our maritime history.

Photo Above: Dec. 7, 1941, in Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. Two U.S. Navy launches work near the capsized hull of the U.S.S. Oklahoma.

In 1952, four U.S. Coast Guardsmen made history when they performed a daring suicide mission in a 36-foot motor lifeboat facing hurricane-force winds and seventy-foot waves to rescue 36 crewmen from the SS Pendleton, lost off Cape Cod. It was the most incredible motor lifeboat rescue in Coast Guard history and was recently immortalized in the movie “The Finest Hours” released by Disney Pictures in 2016. The film was based on a book of the same name written by Michael J. Tougias and Casey Sherman.

Photo Above: 36-foot U.S. Coast Guard Motor Lifeboat.

A century earlier, the U.S. Life Saving Service (U.S.L.S.S.), the U.S. Coast Guard’s forerunner, would train surfmen to launch lifeboats from wagons rolled into the surf to rescue individuals trapped on sinking vessels up and down the coast of the United States. One most notable area was the Outer Banks of North Carolina, dubbed “The Graveyard of the Atlantic.” The work was so dangerous; their motto was, “You have to go out; you don’t have to come back.”

Photo Above: Two 19th Century photos of U.S.L.S.S. crews with their lifeboats.

These wooden work boat’s designs had been honed and improved over time from vessels developed in the old world and made their way to our shores from Europe, particularly Scandinavia and the British Isles.

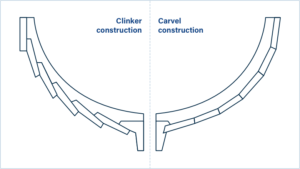

Heritage Boatworks, a Nation’s Oldest Port® program made up of a group of dedicated boat-building volunteers at the St. Augustine Lighthouse & Maritime Museum, have resurrected one such vessel. The 1760 era British “Yawl” was the 18th-century workhorse of the British Royal Navy. They were sturdy boats generally between 16 and 18 feet in length and, early on, were considered “clinker-built,” meaning that the vessel’s hull planks overlapped at the edges. Also called lapstrake planking, this technique was developed in Scandinavia. The Norwegian “Yole” was a small, sturdy fishing vessel sold in kits to the Irish and assembled by the Norwegian boat builders on arrival. The Norwegian design soon populated the Islands of Scotland and Britain in the 16th and 17th Centuries.

Photo Above Left: 19th Century Norwegian Yoles off the coast of Scotland; and Photo Above Right: Clinker vs. Carvel planking.

The English then took the design and made changes to improve cargo capacity. They replaced the sharp stern with a broader transom and made the bow blunter, increasing the number of rowers and goods that the vessel could transport. The word “Yole” morphed eventually into “Yawl,” and the lapstrake planking was replaced with an in-line method called “carvel planking.” They could be fitted with a mast and sail (as could the Yole), and sailors began to refer to their Yawls as “Jolly Boats” or merely a “Ship’s Boat.”

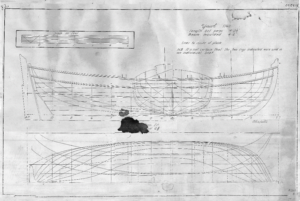

Photo Above: Plans for the 1760 Yawl discovered during research by the St. Augustine Lighthouse & Maritime Museum’s archaeologists.

Photo Above: Ship’s Boat (Yawl) of H.M.S. Victory, Lord Nelson’s Flagship, Portsmouth, England.

These sturdy boats are built on a frame called a strongback. Forms that determine the hull shape are laid out on the keel after it is set on the strongback, and the boat frames and planking are built around the forms. Planking work may be done upright with forms secured to an overhead beam as pictured below or be done with the vessel inverted (see below) after framing is complete.

Photos Above: Heritage Boat Builder Dr. Jim Gaskins lays the keel on the strongback. The Yawl takes shape at the Museum Boat Works. Note the keel that’s sitting on the strongback and forms extending down from above. This was the first of two 1760 British Yawl boats built on the Museum grounds.

The second Yawl was framed in the upright position and then inverted on the strongback for planking. The beautiful lines of the carvel planking are noted, specifically where the hull planks curve back and meet the transom at the vessel’s stern. This Yawl will soon be righted to finish its fitting for the sea. The builders of these beautiful wooden vessels are all Museum volunteers who have a deep desire to preserve this dying art and are devoted to their work of retaining our maritime traditions and connection to the sea.

Photos Above: The Yawl lines at both bow and stern are simplistic beauty and functional for a working boat. The work requires extensive mathematic calculations to achieve the desired results. This was true for 17th and 18th Century shipwrights as well.

The seams between the planking will be calked with cotton batting using a calking iron and mallet. Historically, the cotton was tarred with a pitch before calking. Pitch was harvested heavily from the pine forests of Florida, Georgia, and the Carolinas in the early history of colonists arriving in North America. Production of these “Ship’s Stores” was one of the very first industries in colonial America.

Photo Above: The launch of the first 1760 British Yawl in Salt Run below the St. Augustine Lighthouse & Maritime Museum.

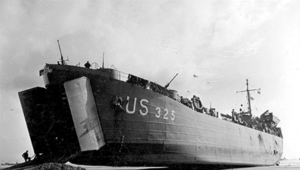

From the Navy launches at Pearl Harbor to the Higgins Boats and L.S.T.’s operating with the Allied forces at Normandy during Operation Overlord, the evolution of vessels that move people and goods, soldiers and supplies, as well as the people who build and operate them, have all contributed to our nation’s maritime traditions. Keeping these traditions alive is a primary mission of the St. Augustine Lighthouse & Maritime Museum. You may visit our Heritage Boat Builders at the Museum, generally on Tuesday, Wednesday, or Thursday mornings before noon, to appreciate the fine craftsmanship they produce every week, or you may consider becoming a volunteer yourself.

Photos Above: Higgins Boat landing craft and the larger L.S.T. delivering troops, vehicles, and supplies on D-Day, Jun. 6, 1944.

No matter how large or small, the ship’s boat, known as the Yawl, is one of a few vessels that started it all. A bit of well-crafted wood, a rigged sail, and a crew to row her is all that is needed to have a look back in time to our humble beginnings of humans working on the water.

About the Author: Rick Cain

Rick Cain has worked for the St. Augustine Lighthouse & Maritime Museum for 18 years after a 20-year career as a health care professional.

He serves on the Board of Directors of the American Lighthouse Council and is Immediate Past Chair of the Florida Attractions Association. He also works closely with the United States Coast Guard to maintain their historical ties to the Museum.