When we think of U.S. Naval Aviation, most of us immediately picture the mighty aircraft carriers, decks bristling with a wide array of aviation assets that can take to the sky at a moment’s notice. But aircraft carriers, as impressive as they are, are not the only vessels to launch and recover aircraft while underway at sea. In fact, they were not the first to do so either. Navies worldwide began launching and recovering aircraft from destroyer and cruiser class ships at the turn of the 20th Century, followed by, with few exceptions, the development of the first U.S. aircraft carriers in the 1920s. This article focuses on one of the mightiest “little” planes in the U.S. arsenal in World War II; the Curtiss S.O.C. “Seagull.”

CURTISS SOC SEAGULL (in seaplane configuration)

Produced by the Curtiss-Wright Corporation, the Seagull first took flight in 1934 and served not only the U.S. Navy but also the U.S. Marine Corps and U.S. Coast Guard through the end of WWII. The scout-observation plane had a crew of two; one pilot who had control of the aircraft and a forward-facing Browning M2 AN machine gun, and one observer who also served as a rear gunner utilizing a flexible-mounted Browning M2. The plane could also carry up to 650 pounds of small bombs under its wings. It could be configured with regular landing gear for landing at airfields or on aircraft carrier decks or be configured with seaplane pontoons. It had a cruising speed of 116 knots and an operational range of 587 nautical miles.

This little bi-plane, which looked as though it belonged to a bygone era, proved most useful as a seaplane. It served aboard ships that would be the last thing one would think of has having aircraft that could be launched and recovered while underway at sea. Almost all of the training for the Seagull would be done from bases here in Florida. To achieve this, cruiser and destroyer class vessels were equipped with two catapult rails to launch the small planes and utilized a ship’s crane to recover the aircraft.

TWO SOC SEAGULLS PREPARING FOR LAUNCH

When stowed and underway, the plane’s wings folded back against the fuselage, and the catapult rails, located at the vessel’s stern, ran from bow to stern in line with the vessel’s deck. The rails could be swung across the ship’s beam at an outboard angle of 30 degrees atop rotating turrets when preparing to launch. Then the plane’s wings were deployed. Four catapults were utilized, each powered by a different method; compressed air, gunpowder, hydraulics, or flywheel. Though this was easier said than done, the aircraft’s launch could be achieved by turning the vessel into the wind. The rails could be turned to 45 degrees in certain conditions, but this made launching the planes even more difficult.

Just having the aircraft aboard was fraught with danger. Storing highly flammable aircraft fuel created a much more significant fire hazard for the vessel, hence the necessity of keeping the aircraft, its fuel, and catapults in the stern and away from the larger gun turrets and shells, the ship’s primary weapons at sea. The Seagulls’ mission was reconnaissance, anti-submarine and anti-enemy spotter aircraft, and sea rescue operations. The pilots who flew these planes had to be very skilled indeed. Training took place at N.A.S. Jacksonville and N.A.S. Pensacola, while final check-out training at sea was done out of Port Everglades, Florida, aboard the U.S.S. Absecon.

Landing and recovery of the planes proved to be as challenging, if not more so. Landing on water is easy, as long as the water is calm. That was rarely the case in the open sea so that the ship would make a wide turn, or a series of turns, to flatten the water surface for the planes to land. It would then be up to the pilot to maneuver his plane alongside the vessel without damaging his wings against the ship’s side. If seas were rough, an aluminum mat with a hook could be dragged over the side, creating a smooth run-up surface for the aircraft. Once on the mat, the pilot could cut his engines, and the hook would engage as the plane slid backward. The pilot would climb up from his cockpit and attach the crane hook for a ride back aboard his vessel via a winch on the crane. It was challenging to say the least. Occasionally, seas were so rough, and the pilot would have to land in the ship’s wake before running up alongside.

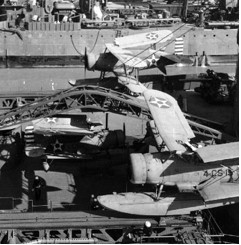

RECOVERY AT SEA (*note that the plane on the left is the larger monoplane Curtiss “Seamew”)

The sturdy little Seagull was compact, reliable, and a workhorse for Curtiss and the United States Military. But with the ongoing improvements in aviation, Curtiss introduced its next plane to replace the humble Seagull. It was the SO3C “Seamew,” a monoplane that was larger and more powerful. The Seagulls were pulled out of active service and sent back stateside to be retrofitted as trainers for young cadets learning to fly. Unfortunately, the new Seamew was immediately plagued with problems, the primary one being severe instability while in flight. Navy, Coast Guard, and Marine Corps pilots hated and dreaded flying them. While the Curtiss Corporation scrambled to make changes to improve the aircraft, the U.S. Armed Services simply gave up on the SO3C Seamew. They returned the reliable S.O.C. Seagulls to active service, where they continued to serve with distinction until the end of the war in various capacities.

A MECHANIC AND CREW TAKE A BREAK IN PORT

TWO SOC SEAGULLS DEPLOY THEIR FOLDED WINGS

The use of rail catapults aboard cruisers and destroyers, however useful, was short-lived. Patrol aircraft could be launched and recovered much more quickly and reliably from aircraft carriers. By the mid to late 1940s, catapult rails would be replaced with new helicopter landing pads, the first of such aircraft seeing action in the China-Burma-India theater near the end of WWII.

Most of the Curtiss Seagulls were scrapped as the war came to an end, but for a short time, crews of determined men were trained here in our home state of Florida and then deployed to fly some of the most challenging missions ever to take place on the world’s oceans. Many downed pilots and sailors, adrift in the sea, owed their rescue to Seagull crews. The crews either provided cover fire for protection, relayed their position to friendly ships, or simply landed their planes on the ocean surface and allowed the stranded men to climb onto the wings. They would then wait for rescue or taxi their plane back to their ship regardless of the risk to themselves or their aircraft.

The next time you are out taking a stroll on the beach, and you hear a seagull cry, look overhead and out to sea. Take a quiet moment to remember the S.O.C. Seagull and the crews who made them fly, and perhaps share their story with a friend. The service of these American heroes should never be forgotten.

U.S.S. ARIZONA, 1940, ONE YEAR BEFORE THE ATTACK AT PEARL HARBOR, SPORTING TWO SEAGULLS ON HER STERN

*all photos are in public domain