Mary Postell

A freed slave after the American Revolutionary War, Mary Postell was born in South Carolina, enslaved again in St. Augustine, Florida, where she and her daughter were kidnapped, and then taken to Nova Scotia, Canada, by her owner in 1786. In St. Augustine and Canada, Mary tried to prove her freedom in court houses. Her story was written below for a presentation for summer camp students at the St. Augustine Lighthouse & Maritime Museum. Documents and history accounts for this story are provided in links following the story.

#BecauseOfHerStory is a series for Smithsonian Affliate museums to share stories about women who have shaped America as we know it through their work, creativity, and resolve. Learn more here: womenshistory.si.edu/herstory

HER STORY

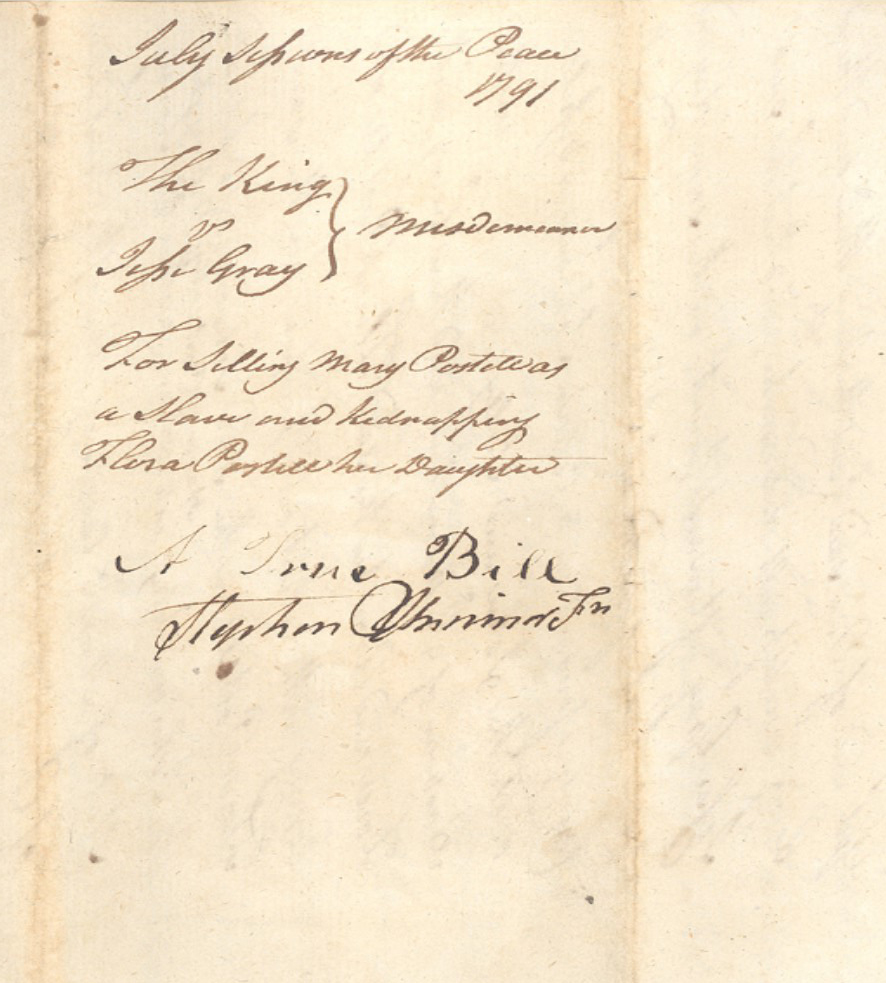

A document from Nova Scotia, Canada dated July 1971 that shows the sale of Mary Postell and the kidnapping of her daughter, Flora Postell.

They were hard times in those days and when the war for independence began, life got harder. My name is Mary Postell and I was born in South Carolina, living near the Santee River about 40 miles west of Charles Town. I belonged to a man named Elisha Postell, who believed that we shouldn’t be governed by the English King. Elisha died early in the first skirmishes and his wife remarried a Mr. Wearing, who also wanted a country free of British rule, however some of his people were loyal to the King. So, some of his folks joined the British, while some of us folks ran away to work for the British. Either way, many of us found ourselves with the British at Charles Town in 1780.

Before we ran, we heard that if we gave our time to work as laborers or soldiers, we would be considered Black Loyalists. That meant that we were to be free after the war! If we stayed put and our home was one of the rebel properties confiscated by the British, we’d be called “sequestered” and could be bought, sold, or taken away.

So, I ran! I found work under Colonel James Moncrieff, who saw over hundreds of Black Loyalists in engineering and ordnance operations, which is artillery and weaponry. My time was spent in Public Works and Forts, while my husband William Wearon was an artificer, or maker of explosive devices. When the war ended, the rebels had taken Charles Town back and all those people loyal to the British would need to evacuate. There was a British officer that gave ‘Certificates of Protection’ to those Black Loyalists that helped out. This certificate would prove their free status. I got one for myself, but a John MacDougal asked me if he could look at it and he never gave it back! After that, because I could not leave town without the paper, my husband persuaded me to go to St Augustine in the service of Jesse Gray, who was a white Loyalist. So I did. It was 1783 and I never saw my husband again.

I was in St Augustine and had gone to the State House hoping to get help with proving my freedom without a certificate. Jesse Gray found me there and took me and my 2 year old daughter, Flora, off to his Brother Samuel’s house. He lived around Saint Johns Bluff away from town near what is now the Georgia border and he was an outlaw. Both the Grays were part of rough bandit gangs that stole horses and cattle, robbed people, and destroyed property. No one was safe! My daughter and I were with Samuel for about 2 years and I could find no one to help me get away in the lawless area. I had my second child, Nelly, during this time.

With the end of the war, Britain gave Florida back to Spain and those still living there had a few choices to make. You could stay, give an oath to be loyal to Spain, and convert to the Catholic faith; or you could leave by ship and go to a different British colony, where you could receive land. Most everyone opted to leave on the British supply ships that were sent to move folks out of St Augustine. Although it would be hard for Spain to enforce their laws in our parts, Jesse decided he would go. He took me and my children and put us on a transport ship in July of 1785. Samuel stayed put.

Our ship, called the Spring, was the last non-military ship to leave St Augustine. Jesse forced us to stay in the cargo hold for the 25 days it took to sail to the Bahamas and then to Shelburne, Nova Scotia, in Canada. It was dark and stifling hot with no air movement. It was also difficult to stand with the ship’s motion whether it was swaying to and fro, or heaving up and down. Sleep was impossible and many weary tears were shed by my daughters and I was hard pressed to find the strength to comfort them. We landed in January of 1786.

I did not trust Jesse on wit, so at the first possible chance I ran away with my children. Jesse had gone to survey land in a different county. I grabbed my girls and took what we could carry. I found work as a laundress and a house to rent a little to the north. After about 3 months, Jesse came back and found me. He needed me and my daughters in his home because the more people in your household, the more land you were given. We helped raise Jesse’s land allotment from 100 to 200 acres.

In my short time in Nova Scotia, I had seen many Black Loyalists, free folks, being held as slaves or indentured servants and they were no longer free. Some of those folks filed court cases against their captors. Even though Jesse had listed us as servants in his land allotment paperwork, I was afraid that he would say I was a runaway slave and sell myself or my daughters. I filed a challenge against Jesse with the Shelburne County Court and he was charged with kidnapping. Unknown to me, Jesse had a bill of sale from his brother, Samuel, and 3 people to testify that the signatures were real. John Fanning, Samuel Andrews, and William Mangrum also swore that it was commonly known that I was Samuel Gray’s slave in Florida. I denied that there was any purchase for me and told the court my story. The court decided in Jesse’s favor, although he would not be allowed to sell or send me anywhere during the next year. I was outraged and disheartened! The witness, Samuel Andrews, had already been to court where his servant challenged Andrews for his freedom, too. The other 2 witnesses were part of the bandit gangs that were in Florida. How could the court be tricked like this?

I t was about 16 months later that Jesse sold me to William Mangrum for 100 bushels of potatoes, which would be about $2,500 today. I was glad to be away from him as he used me in such an ill manner, but my heart broke to be away from my girls. I worked for Mangrum for about 3 years when my worst nightmare comes true. Jesse sold my oldest daughter, Flora, to a Scottish trader named John Henderson. Henderson wanted to take her with him to Wilmington, North Carolina in America. Now I would never see her again!

I decided to challenge Jesse Gray in court again. This time, I had my own witnesses! I had to prove that I was free and therefore, my daughters were too. This time, Jesse told the official he had originally purchased me and Flora from Joseph Rea at the State House in St Augustine in 1783. He said Rea brought me to St Augustine from Charles Town. Jesse then claimed he sold us to his brother and then repurchased us along with Nelly before coming to Nova Scotia. I told them how I went with Jesse from Charlestown to St Augustine and I never knew of any sales. My witnesses, Scipio and Dinah Wearing, attested that I was free and had worked alongside them for the British. Scipio and Dinah were part of the household I originally fled from. Surely the court would listen to my witnesses. While they were in court testifying, their house was set on fire and my friends lost their home, furniture, clothing, and one of their children. It was heart-wrenching!

Sadly, in the end, it did not matter. Jesse was found not guilty, no one gained their freedom, I lost my Flora, and eventually my Nelly. I was inconsolable!

DOCUMENT LINKS

Mary Postell legal documents

https://novascotia.ca/archives/africanns/archives.asp?ID=46&Page=200402069&Language

Mary Postell’s husband named

http://www.royalprovincial.com/military/civil/rar/rarretn2.htm

Brief Summary

http://blackloyalist.com/cdc/documents/official/postell_case.htm

Black Loyalists in Canada

Black Loyalists

https://blackthen.com/mary-postell-escaped-slavery-took-refuge-within-british-lines/

Mary Postell – poem

https://journals.lib.unb.ca/index.php/acadiensis/article/view/11149/11872