Keepers of the Light

Alphonso Daniels, 2nd Assistant Keeper, 1928 St. Augustine Lighthouse

When you think about lighthouse keepers, what comes to mind? Maybe it is long, lonely nights dutifully keeping the lamps burning for ships unseen. Alternatively, perhaps it is a long day spent painting the lighthouse tower. Lighthouse keeping meant a hard life, especially as we think about it today. Who do you imagine did these tasks?

During the lighthouse boom of the 19th century, jobs requiring a rugged self-reliance would have been male dominated endeavors. While both sexes had worked equally hard on the frontier during the 17th and 18th centuries, the Industrial Revolution cemented for the next 200-years western views of men’s role as the worker and women’s role in the house. The Lighthouse Service was no exception to this rule. Even though entire families worked from dawn until dusk at light stations across the country, males made up the overwhelming majority of government appointed lighthouse keepers, who received pay for the work they performed.

It was often necessary for women to serve too even though many were not rewarded officially. When conditions permitted families to live on a light station everyone helped. Keepers’ wives assisted their husbands in critical capacities. They tended a garden, fed livestock, managed supplies, and inventoried equipment including household goods. Women helped pass the white glove inspections when supply ships carrying inspectors visited. If a station won an efficiency pennant from the Lighthouse Service, then it was because of everyone’s effort. With a mandate to keep the light on no matter what, wives and daughters no doubt lit the lamps as well. Nothing about this was uncommon.

In some instances, women became official guardians of the light. The 1883 United States Treasury Register lists the nation’s lighthouse keepers. Treasury agents provided salaries to several wives and daughters who were assistant keepers. In the Sixth District, which included the St. Augustine Lighthouse, agents noted three women keepers. Bridget Conner was the assistant keeper to her husband, Patrick at the Daufuskie Island Range Light in South Carolina, making $400 a year. Patrick made $560 or about $12,430 in today’s dollars. Sophronia Bradwell was the assistant keeper to her husband, John at the Wolfe Island Range Light in Georgia. The Bradwells earned the same respective pay as the Conners. At the St. Johns River Light, Francis McDonald served with her husband, Alexander. She made $400 a year, and Alexander made $600 or about $13,314.00 today. Keeper’s families,

of course, had housing, fuel oil and other necessities provided.

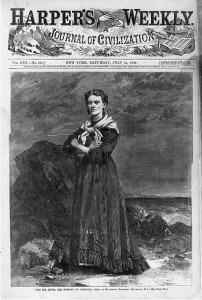

In some cases, keepers’ wives and daughters took over for husbands or fathers no longer able to perform their duties. Ida Lewis is the most famous example. Her father had a stroke not long after moving to the Lime Rock Light Station off Newport, RI. Ida’s heroism in rescuing people from the sea earned her national fame. Ida was also among the most well paid head Lighthouse keepers at $750 per annum. She even appeared on the cover of Harper’s Weekly in 1869 (right).

At the St. Augustine Lighthouse, Head Keeper William Harn passed away in 1889 from tuberculosis. Harn probably contracted TB while he was a Union officer in the American Civil War. His military records list many health problems. Harn’s wife Kate Skillen Harn became Second Assistant Keeper after his death. She almost certainly helped him throughout their 14-year tenure. Serving as a second assistant keeper allowed Kate to support her six daughters until she received William’s pension. Kate was supremely qualified to step in, and did so for six months. She then moved her family to town for a few years before moving back to her home state of Maine.

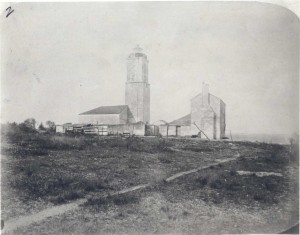

Before Kate Harn, another woman served as head lighthouse keeper at St. Augustine. Her name was Maria De Los Delores Mestre Andreu. Maria became keeper at the first St. Augustine Lighthouse, (sometimes called the Old Spanish Watchtower) in 1859 after her husband Joseph Andreu fell to his death while whitewashing the tower. The local newspaper carried a graphic account of the accident. Maria then waited several weeks for the government to appoint her officially, but as far as we know, the light continued to shine.

Maria Andreu was keeper at the Old St. Augustine Lighthouse; it was from this tower that Arnau and Nelligan removed the lens during the Civil War

Widow Andreu served in this capacity until the American Civil War, when Confederate sympathizer and fellow Minorcan, Paul Arnau hired a man named Nelligan to remove the fourth-order Fresnel lens from the tower. Arnau hid the lens and clockworks, temporarily decommissioning the light. Maria must have at least known of the planned removal, and she probably provided access to the lens room. After the Union had taken over St. Augustine peacefully, Maria moved to Georgia to be with family. Union forces arrested Arnau and held him aboard a gunboat until he finally gave up the stolen equipment.

As with many other keepers’ wives, Maria was completely qualified. Given her Minorcan heritage, the United States Coast Guard has recognized Maria as the first Hispanic-American woman to serve in the United States Coast Guard or its predecessor services. She was also the first to command a federal shore installation.

In whatever way women came to tend the light, they proved to be every bit the equal of their male counterparts. Many, like Kate Harn and Maria Andreu, supported their families through times of great stress and hardship while working to keep their communities safe.

Paul Zielinski is Director of Interpretation for the St. Augustine Lighthouse & Maritime Museum. He received his master’s degree in Public History from the University of West Florida and joined the lighthouse family in 2011.