A huge truck nearly ran me off the road, whizzing past only inches away. As the horn blare tapered off, I realized rubbernecking on this stretch of road is a full-contact sport. Late September found me on one of the most industrial roads in America, yet deep in the heart of the bayou.

Highway 1 winds south from the Mississippi River, tracing through Belle Rose, Thibodaux (don’t pronounce the ‘h’), Galliano, Golden Meadows, and finally to Grand Isle. The farther south you drive, land gives way to water. The world becomes water sprinkled with dry spots and cut channels. Bayou Lafourche Canal is one of the channels and parallels Highway 1. On dry patches, only inches above the tide, are construction yards, supply depots, welding shops, shipyards, and fenced lots full of giant prehistoric plumbing components. The road is a major artery of the oil business, although a new, raised version of the road flies well above the bayou like a giant concrete millipede.

En route to Patterson, Louisiana for an oral history interview, my schedule changed and I ended up with a day in-limbo. Reconfiguring quickly, it was a rare opportunity to explore the sponge-like coast of Louisiana. I armed myself with tips and tricks from friends who knew the area, and who knew where to eat. Visiting Louisiana, especially Cajun Country, without intending to feast is like a pencil without a lead. Pointless.

Years ago, I was invited on a trip to Patterson to meet the Felterman family. Related to the Versaggi family of St. Augustine, and a dynastic family of the commercial shrimping industry, the opportunity to meet, and record Felterman family history was more than tempting.

“You’re a fool Brendan, it’s the peak of crawfish season and we’re going to be in the middle of the action.” said Grace Paaso, my invitee and one of the Versaggi family keepers of the flame.

“I know.” I muttered.

“Plus, you’re missing out on work boats, antique engines, and all the shrimp boat stories you can handle.”

“Don’t rub it in Grace, it’s a no-go.” I begrudged.

And so this couillon (koo-yon = Cajun for idiot) stuck to his desk, sorely aware of the raucous bayou boogaloo, replete with hot mudbugs, cold beer, and Cajun history flowing like crude from a gusher. Seven years later, I didn’t repeat the mistake.

In early September, my friend John Versaggi found out I was headed to Pensacola for a conference and immediately chimed “Heck, why don’t you continue to Patterson and visit Uncle Butch? It’s only a few hours west.”

He was right. I grabbed a voice recorder, notepad, and immediately started fasting.

On the Road

On my way down, and up, Highway 1, then west on State Road 182 Louisiana unrolled in front of the truck. At dawn, driving west from Houma, fog lay over giant green lawns of sugarcane. Some of the fields seemed to carry well over the horizon with cane tops nodding sleepily in the dark-pink light. From underneath the truck, a rhythmic clap-de-clap of concrete road sections whopped out a beat easily joined by fiddle, accordion, and triangle.

Where 182 cuts through Morgan City it crosses one of Louisiana’s riverine grand dames, the Atchafalaya. Serving southern Louisiana’s oil, boatbuilding, and fishing industries the Atchafalaya was once the principle mouth of the Mississippi. Were it not for the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and one of the grandest control structures ever engineered, the Atchafalaya would re-take its ancient role, steal the Mississippi Delta wholesale, cut New Orleans off from oceanic trade, and redirect the bounty of the Midwest down through the port of Morgan City. In 1963, the Old River Control Structure, a five-million ton mass of concrete and iron gates connected the two rivers through engineered diplomacy and roughly one-third of the Mississippi quietly flows through downtown Morgan City.

The first stop of the day was at one of the oldest boatbuilding yards on the Gulf Coast. Conrad Industries has built ships, fishing boats, ferries, barges, and oil service vessels in downtown Morgan City since 1948. The progenitor was J. Parker Conrad. Seven years ago, I cold-called the shipyard and by lucky chance spoke directly with Mr. Conrad. After introducing myself as a historian working on the history of building shrimp trawlers, he opened up and 45 minutes later we were well into the Conrad story.

What unrolled from Mr. Conrad was, to me, unexpected. A Greek boatbuilder moved from my neck of the woods to Morgan City during the 1930s. Stathis Klonaris built traditional Florida-style shrimp trawlers, completely unlike Gulf boats. As shrimping put down roots along the Gulf, the need for trawlers increased. Klonaris bought land, put up a shed, and built to supply the boom. In 1947 a man with little business experience and a failed attempt as a traveling minister bought the yard from Klonaris. J. Parker Conrad knew the ‘old Greek’ was doing things right and sought to capitalize on the company’s reputation and product. In 1948 Conrad Industries Inc. was founded with the motto “Quality is remembered long after prices are forgotten!” Like few of their competitors, Conrad planked boats with mahogany and plugged-over planking nails rather than smearing the holes with putty. Any shrimp boat owner who ever tried to sand their hull can appreciate the value of this. Sanding puttied hulls removes galvanizing from shallowly-driven nail-heads, causing a dappled rust-streaking almost immediately after a fresh coat of paint.

To find where the Conrad shrimp boats were built, I pulled onto Front Street. Following the river, a 21’ concrete wall blocks all views of the waterfront and is a thread of protection for downtown Morgan City. While at first it seems such a shame to wall off a river, it must be powerful peace of mind for folks who −during pre-floodwall years−watched muddy water creep slowly into their living rooms. At intervals, open gates allow vehicular access to the real waterfront and when I got to Onstead and Front, I turned left through a wall that transformed the world from azalea beds to the Jurassic world of a shipyard replete with ships sulking on blocks, fountains of sparks everywhere, and the perpetual clanging and banging of industry.

Forklifts buzzed by, a truck bearing a fresh load of steel idled impatiently behind me as a kind-faced woman stepped from her guard shack. Thinking I was probably lost, she came close to overcome the thrum of yard activity to hear my plight. Yelling over the noise…

“I’m here to deliver a book to Mr. Conrad senior. We spoke a number of years ago and he’s not expecting it but I’d like to drop it off for him!”

“Turn around, head down that way” smiled the guardess, pointing “park in a delivery spot, and proceed up the brown stairs!”

Parked, I found the stairs and climbed to the shipyard office. It was still early in the morning and none of the family had arrived. Mr. Conrad was, to my pleasure, still very much alive although he no longer comes to the yard, I was told. His son, “Mister Johnny”, is company president and was out to a meeting. Leaving the book with his secretary, it felt nice to complete a minor loop of sharing information with J. Parker Conrad; a repayment for his time sharing company and personal history a few years prior. I don’t know if I’ll ever meet him or talk with him again but glad to have had at least one chance to share our interest for the same patch in history.

Pulling the truck back onto Front St., I turned into a waterfront reserved for fishing boats. Beneath and between two archaic iron truss bridges two skimmer boats barely surged calmly at their moorings. Netting, draped and bunched from folded butterfly skimmers, gave the boats a surly appearance like a pelican atop a piling. The brown water of the Atchafalaya, stolen from the Mississippi, flowed by giving off a reddish rusty hue complimenting the noisy iron bridges above. Traffic on the river was limited to a few logs and sticks slowly making their way downstream. Silently from the far bank, a blue and white-housed tugboat pulled into the stream, built up a white foam moustache, and headed downriver for an unseen string of barges.

Back on 182, I pulled into Patterson for my first real destination. The Wedell-Williams Aviation and Cypress Sawmill Museum is one of a network of Louisiana state museums. Split between two hangar-like buildings, the museum hosts an excellent collection of pre-war air racing planes and replicas. Jimmy Wedell, famous racing pilot of the 1920s and 30s, met Harry Williams, a local cypress/sugar/oil millionaire and the two became famous for their racing empire and started an air mail company out of Patterson. The 1930s were a time of transition for Patterson. Frank B. Williams, once known as the ‘Cypress King’, owned the largest sawmill in the world. But, by the late 1920s, cypress swamps had been cut to the last stump. Oil quickly grabbed the attention of men with money and ambition and southern Louisiana crawled with speculators and wildcatters. The big sawmills were left to rust and rot.

Patterson has done a fine job of remembering those days, when time and wealth were measured by the million-board-feet. Located on the south side of highway 90, the Aviation and Cypress Sawmill Museum is a branch of the Louisiana State Museum. Within its elegant hangar-style complex are exhibits on the Wedell-Williams Air Service, air racing, and the cypress industry. Sitting in wooden stadium-style seating, the visitor is immersed in a 1930s air race, projected across three screens with a reality-enhancing wind – blown from hidden fans that mock the prop-wash of a radial engine.

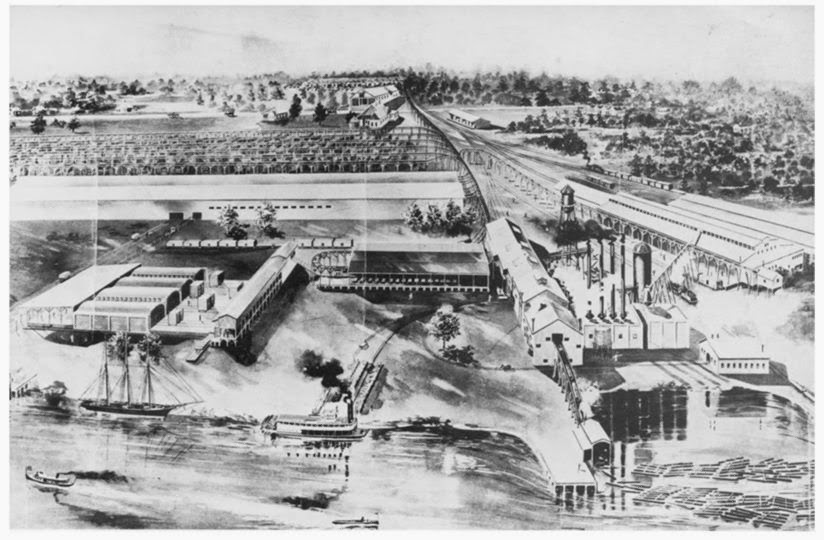

An image appearing in American Lumberman in 1911, this bird’s eye illustration of the F.B. Williams Cypress Company shows the magnitude of the cypress industry, and its effect on the Patterson waterfront. Image courtesy of Albany Woodworks.

Across the foyer an exhibit hall pays tribute to the cypress industry, a part of Louisiana’s fabric as intrinsic as gumbo and muddy water. Mammoth saws, oil soaked winches, and a titantic stump silently testify to the woodsmen, and women, who turned cypress swamps into billions of board feet of lumber. For over a generation, rhythmic blows of felling axes, grating of saws, and the wet thuds of cypress trunks sounded through the bayous as the engine of American industrial destiny fed its esurient maw.

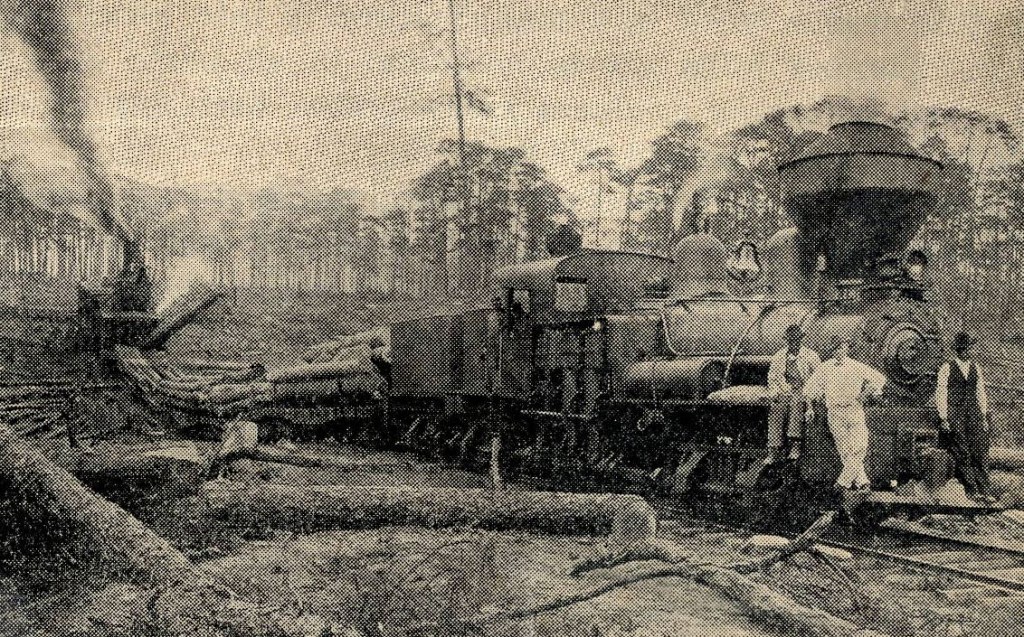

Taken in a Florida cypress swamp, this photo shows a boiler and two winches on the left, one used as a skidding engine to pull logs to a railhead, and the other as a loading engine to lift logs onto special railcars.

When the northern virgin forests of Maine, New York, Pennsylvania, and Michigan were felled timber companies moved like a great threshing machine into the southern swamps. American railroads needed cypress tanks along the railroads, dumping immeasurable quantities of water into hungry locomotive tenders. Pullman railway cars were extensively built from cypress; municipalities used cypress for planking roads, building tramway systems; and American roofing was primarily wood shingle, a perfect application for hardy virgin cypress – indeed billed as an ‘eternal wood’. The need for trees was enormous and logging crews chewed their way through forest after forest, swamp after swamp. With little care for the land, or the locality, many of the lumbering companies were distantly owned by industrialists who boasted their ‘cut out and get out’ practices.

This locomotive, seen in a freshly logged area, is typical of the logging locomotives maintained by F.C. Felterman, Butch’s father. Driven by a side-mounted engine these locomotives were robust and easily adapted to rough logging roads. Photo courtesy of the Louisiana State Museum.

In Louisiana’s rural backwaters, cypress lumbering brought a different mode of life to the people of Cajun country. People of Acadian, African, and German descent found themselves wrapped into an industrial system that created towns where none had existed. The industry also brought trainloads of machinery to the bayous, machinery that was worked to the bone and in need of constant repair. F.C. Felterman Sr. was one of the men who kept the mechanical juggernauts in motion, repairing everything from locomotives to steam winches. A Patterson native, Felterman moved his family to a company camp on the shores of Lake Verret during the mid-1920s. F.B. Williams Cypress Co., based in Patterson, ruled millions of acres of cypress swamps, spattered across the Atchafalaya basin. Thousands of company employees and their families lived out of floating towns and camps that moved with the harvest. Men like Felterman, adroit with head and hand, found valuable niches that could support a family and offer a future for the next generation.

This scene, taken in the southern cypress swamps, is typical of an early logging camp. By the time F.C. Felterman moved his family into the logging scene, lumber companies had moveable structures to create mobile towns, complete with schools and churches.

The next generation’s problem came when the cypress ran out in 1928. Out of almost merciless coincidence, the financial woes of 1929 pulled a dark and smothering blanket over lower Louisiana, pushing many Louisianans into cities or back to a less-industrialized life. Through the next decade, the crushing weight of the Great Depression challenged every city, every town, and every American citizen in an economic struggle for survival.

Fortunately for Patterson, the vacuum created by shuttered cypress mills was partially filled by a spanking-new industry. Among the few American economic sectors expanding during the Great Depression, the little-known southeastern shrimping industry flourished. Born in Florida during Theodore Roosevelt’s presidency, the industry spent its infancy in Fernandina and a boisterous adolescence in St. Augustine. Driven by immigrant initiative, namely Greek boatbuilders and Italian fisherman, the business developed a vitality supporting local stability and extra-regional expansion.

During the 1930s, fleets steamed out of St. Augustine to hunt valuable new shoals of shrimp. One such fleet was that of Felice Golino. Born in Italy in 1896, Golino immigrated to the United States, winding up in northeast Florida. Little is known about his early days but by the early 1930s Golino owned a small fleet of shrimp trawlers in St. Augustine. Felice was a flashy entrepreneur who nobody forgot. He was a shrimp boat captain, a fleet owner, a company manager, was most often seen wearing a pinstripe suit and fedora, an inveterate gambler, and despite the nature of his business, rarely got dirty; he was one of the most unindicted men in the south. Despite his reputation, he was a ruthless entrepreneur and many fishermen sailed profitably in his wake.

The Benito Mussolini, owned by Felice Golino, is seen here in an unidentified location. She was one of the largest shrimp trawlers during the 1930s and represented a state of the art fishing vessel.

By the mid-1930s, the Patterson waterfront was emaciated and economically threadbare. F.B. Williams Cypress Company cut their final log in 1934. For once, the giant blades of the empty sawmill traded their polish for rust. The quietude of economic depression becalmed Patterson for the first time since the 1880s. On an unrecorded date in 1937, Felice Golino’s fleet steamed up the Lower Atchafalaya and into Patterson. Acting on a rumor that good shrimp were to be found along the Louisiana coastline, Golino chose Patterson as his base of operations. The Gulf Coast Fishermen and Trappers Union had denied Golino membership, a prerequisite to unload in Morgan City or Berwick, two towns on the Atchafalaya about eight miles closer to the Gulf. However, Patterson’s aldermen were eager to attract business and so built Golino a packing house on top of a public wharf at the end of Catherine Street.

Golino’s flagship was the Benito Mussolini. Fifty-five feet long, the Mussolini represented the company’s interests and intents. Large, powerful trawlers emerged during the 1930s in response to distant fishing grounds and longer offshore trips. By 1940, the St. Johns Shrimp Company boasted a fleet of over fourteen trawlers and their Patterson fish house unloaded eight other privately-owned boats. After Pearl Harbor, the Benito Mussolini and a sister ship, the General Badoglio, were renamed to save their hides and so emerged the Enterprise and Gulf Clipper.

Taken in St. Augustine during the mid-1930s Felice Golino stands at the bow of his flagship, the Benito Mussolini. Many of these trawlers steamed to Patterson, Louisiana, to begin the commercial shrimping industry there.

The first shrimp company in Patterson, Louisiana was the St. Johns Shrimp Company, a satellite office of Felice Golino’s fishing company based out of St. Augustine, Florida. Note the wooden shrimp boxes ready to hold about 100-lbs of shrimp and ice. Trucking lines connected the Louisiana docks with New York, Boston, Philadelphia, Atlanta, and other burgeoning markets. Photo courtesy of the Felterman family.

Processing millions of shrimp, this photo was taken during the 1950s in the St. Johns Shrimp Co., owned by Felice Golino. The task here is peeling, deveining, and butterflying the shrimp tails. A trough down the center carries a stream of water to wash shrimp heads and peels into the river.

Fishing off Timbalier light, the log of trawler Joan Dora, records on May 15th, 1942 that fishing ceased and the trawler ran for home at 8:10pm in order to avoid danger from German U-boats. Shrimp boats, fishing under the protection of sunlight, and some armed with marine radios to report sightings, were often the first to respond to torpedoed merchantmen; for mariners, World War II combat was only a torpedo away, whether off Long Island or Texas.

A rare shot of shrimp boats coming to the aid of a torpedoed merchantman during World War II. Photo courtesy of the Felterman family.

F.C. Felterman Sr.’s third youngest child, and namesake, joined the Army Corps of Engineers during the war. A missing index finger on one hand prevented military service but young ‘Butch’, as he was known, did his best to make a meaningful contribution. When the war ended, Butch returned to Patterson and like many young men, needed work. In high school, Butch periodically worked aboard shrimp boats, learning how to handle nets, make repairs, and operate winches. The experience proved a natural calling after the war and he returned to fishing.

John Santos, a Patterson fleet owner and St. Augustine native, offered Butch a job aboard one of his boats, the Papa Joe. Not long thereafter, another fleet owner, Bright Kornegay, offered the young Felterman his first command. The skinny skipper and his brother took the trawler Bill Kornegay down to Morgan City to pick up a deckhand for a trip out to the Gulf. A block off the waterfront was the First & Last Chance Bar, a watering hole from which captains regularly filled-out crews. Butch opened the door on a dark, smoky room where men sat with their backs to him. Announcing in a clear voice his need of a deckhand, Butch remembers the men swiveling to meet his face, and going right back to their beers. On his way back to the boat, the crewless Capt. Felterman met a tall, skinny fellow who said he was looking for work on a shrimp boat. His name was John Susky and had never been to sea. The Felterman brothers gladly took in their raw recruit and slipped lines for Ship Shoal.

For the next several years Capt. Butch Felterman built his fishing reputation and a fleet. By the early 1950s three boats fished under the Felterman name. In 1958, Butch was named the King of the Fleet, also known as a ‘highliner’, for having caught the most shrimp during the previous season. During the early 1960s, one of the company’s best boats, the Courageous, sank in a ‘norther. Her crew survived on an unmanned oil platform for a week before rescue. With insurance money from the loss of the Courageous, Butch contracted the construction of a 72’ steel hull in nearby Raceland. When a bare hull was finished, he towed it to Patterson and installed the engine, rigging, and pilothouse himself. She was named the Galaxie and may be the only shrimp boat built to have only completed one fishing trip. When she returned from her maiden voyage Butch received an offer from Geophysical Services Inc. to charter Galaxie out as a ‘shooting’ boat for a geophysical survey. With the prospect of ready money, he took the contract and prepared for the trip. In the early days of offshore oil exploration, a phalanx of boats would systematically cover the sea. Loaded with tins of explosives, one boat would periodically deploy a timed-charge to create a sound wave that ‘listening’ boats would record. Creating a map of the earth’s layers, geophysicists could locate anticlines holding vast pools of oil.

This scene from the 1930s shows boat crews taking a moments rest. Note the wooden A-frames used to handle nets, the large coils of trawl line stowed on deck, and the winch. These boats were likely built in St. Augustine and Fernandina. Photo courtesy of the Felterman family.

Butch remembers loading his boat with explosives as a touchy issue. More than two tractor trailer loads of Nitromex were loaded into the fish hold and secured on deck. Each can of explosive contained 50-lbs and two were routinely tipped overboard per ‘shot’. The Galaxie may have been a floating bomb, but she was making more, and more regular, money than fishing. During the late 1950s, the Felterman family divested themselves of shrimp boats, and constructed oilfield service boats to supply a booming industry. By the 1990s, Galaxie Marine Services had grown to a fleet of 22 boats, all over 100’ long.

Despite his departure from the shrimp industry, Butch never turned his back on its history. Almost single-handed, he has worked to reassemble the pieces of a now-defunct industry in his native town. Patterson no longer supports a blue water fishing fleet and the few surviving fish houses haven’t seen a shrimp in decades. But, along the Lower Atchafalaya, Butch has built a monument to historic shrimping. In a building replicated after the Roanoke River light station in North Carolina, Butch has created a fisherman’s museum. This private collection of artifacts, pictures, stories, and memorabilia documents Patterson’s fishing heritage.

The inside of the Fishermen’s Light is a private museum dedicated to the shrimping industry of Patterson and all of the people who made it possible. Butch Felterman has collected and curated photographs and artifacts from a bygone era and they are well-displayed and interpreted in this elegant exhibit.

At first, I was there to learn about Patterson’s history, an obvious mission. But, what confronted me was quite unexpected. The sheer amount of interaction between my town, St. Augustine, and Patterson – especially during the 1930s and 40s – was profound. I was aware of the connection but did not realize the scope. Almost every name that Butch has in his collection was originally from the Ancient City, had a cousin there, or had close business ties there. It was as if Patterson had formed as a type of colonial outpost in the world of shrimping expansionism. This was, I would find out, to be very true. Not only did Golino bring a fleet and start the first fish house, a true royal family of shrimping dropped anchor in Patterson.

St. Augustine Cousins

The Versaggi family first caught shrimp in Fernandina, Florida during the late 00’s of the 20th century. Related to the Salvadors, another progenitive family of the industry, the Versaggis built a modest business catching and selling shrimp around northeast Florida. In 1923, the family moved to St. Augustine, expanded their fleet, and set up a fish house trading with the largest fish exchange in the world, New York’s Fulton Fish Market. Five brothers, John, Manuel, Virgil, Joe, and Dominic became the core of the Versaggi establishment after their father, Salvatore, died unexpectedly in 1925. Salvatore’s wife, Vincenzina, determined to continue the family shrimp business and enlisted her oldest son, John, to help run the operation. At 19, John took his father’s role and led their enterprise into the next generation and a new period of dynamic growth. As each brother came of age, they filled a role in the company –Virgil explored for new fishing grounds, Joe moved to New York to manage sales, Manuel shuttled between the Gulf and New York, and Dominic returned to the business after attending the Naval Academy and spending World War II in the South Pacific.

Not long after Golino’s gold strike in the Gulf, John Versaggi brought a fleet of boats over from St. Augustine. While setting up on the Patterson waterfront, John fell in love with a young lady born in Napoleonville. Mary Felterman, hereinafter known as ‘Hon’, married John Versaggi in 1947. Hon’s brother was Butch. The marriage bonded not only John to Hon, but two respected families and cities.

Making the Connection

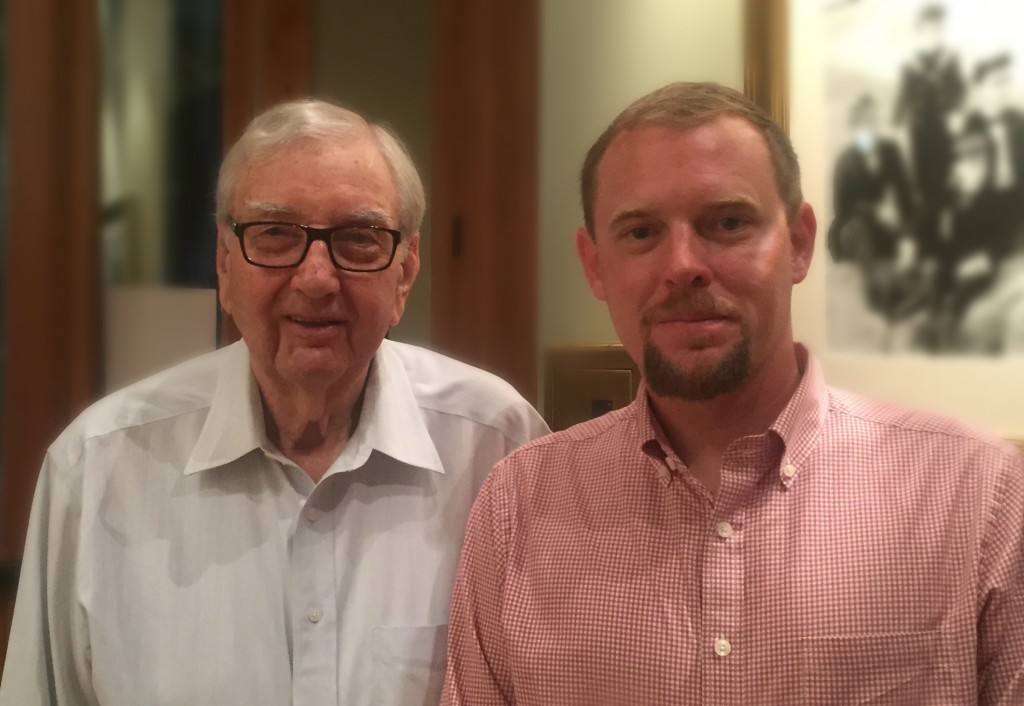

At the hospitality of the Felterman family, I stayed in their museum/lighthouse. On Friday morning Butch knocked on the door for our appointed meeting. With a full shock of white hair, a gentle face, his stature hints of his days as a tall, skinny captain. Raconteur of Atchafalaya history, his dialect has been polished by the bayou – not quite Cajun or Creole – and softly staccatoed with gentility. Butch has spent most of his life on the Lower Atchafalaya, a river for which he has great respect and admiration. A twinkle lights his eye when he hears its name and is quick to correct a speaker that the river is the beautiful Lower Atchafalaya.

The building on the left is a warehouse saved by the Felterman family and is one of the only surviving fish houses in Patterson. Today, it has been restored and is used as a place for the family to host reunions, parties, and events. The lighthouse museum serves as a memorial to the shrimping industry in southern Louisiana and has accommodations for family and guests upstairs.

First things first, I was taken on a tour of their marine facility where today the Felterman family operates a ship custodial service. Laid-up oilfield service boats lined their dock, waiting for a higher oil price to stir up activity in the Gulf of Mexico. Opening the large overhead door to one of their warehouses, Butch and his son unveiled one of their collected jewels, a 10-ton diesel engine. The Feltermans rescued the engine from a sugarcane field where it had sat for more than 50 years powering a mammoth water pump used to drain fields. Today it is part of an engine collection regularly shown, and run, at the Patterson Cypress Sawmill Festival. About running the behemoth, Butch quipped ‘We can’t run it more than a slow idle or the booger to walk off with itself.’ – nodding at the multi-ton steel trailer bolted to the engine.

Weighing in at 10 tons and built in 1923, this engine pumped sugarcane fields dry for years in southern Louisiana. Called a ‘heavy fuel’ engine, it is an early type of compression-ignition engine we now call diesel. With a single cylinder, it produces 100 hp.

Returning to the museum, Butch and I sat down for an interview. He recounted much of what has been told here, a history of two connected cities unrolled. Tapping the table as if to recall certain faces, events, and names he unrolled the history of Patterson shrimping like a tapestry, pointing out each character and event with clarity and order. The tapestry had a lot of familiar names, many from St. Augustine.

Cortez, Florida has fishing roots in the Inner Banks of North Carolina, specifically Carteret County. Despite an intervening century since their migration, the connection is still alive in Cortezian memory. The difference between the cities is that Cortez is still an active fishing community. Patterson is not. The little town and wasn’t a major fishing port, but it played an important role in the diaspora of commercial shrimp fishing from northeast Florida to a very wide world. That same wave of energy expanded throughout the Gulf of Mexico across to Campeche’s azure banks, down through the Caribbean to the mouth of the Essequibo River in Guyana, and finally to the mouth of the Amazon. Through each campaign, St. Augustine was directly involved; at the height of the shrimping boom St. Augustine provided more than one brand new boat per week to the fleet, often headed for international ports.

By 1990 the party was over. The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, UNCLOS, created Exclusive Economic Zones for every maritime country within the United Nations. This process took over a decade but helped protect fishing rights within 200 nautical miles of a country’s coastline. Guyana nationalized the fleet within its harbor overnight, effectively trapping and seizing some U.S.-owned trawlers. Changing political seas, compounded by increased fuel/labor costs and a flood of cheap farmed shrimp from Southeast Asia, put the last nail in the coffin. Big shrimping was dead.

For the people who were a part of it, the rise and fall of commercial shrimping was a dynamic force that changed communities noticeably. Many are now gone, taken with them stories and knowledge of a unique American enterprise. Butch is one of the standard bearers for that history and wants to see it survive. Pointing to a board in his museum that has names of industry participants, he says “Look there, I only have his name, no face. I try and find a picture of every one of them but so many have passed and no-one is left who knows who they were and what they contributed.”

Thanks to Mr. F.C. ‘Butch’ Felterman Jr. and his family, especially his daughter Lisa Kornegay, for warm and generous hospitality. Thanks also, to John Versaggi and his cousin Grace Paaso, for their constant prodding to make time for Patterson, our Gulf Coast cousin.

Brendan Burke joined the St. Augustine Lighthouse & Maritime Museum in 2007 as an archaeologist for the Lighthouse Archaeological Maritime Program. He holds a graduate degree in Anthropology from The College of William & Mary.