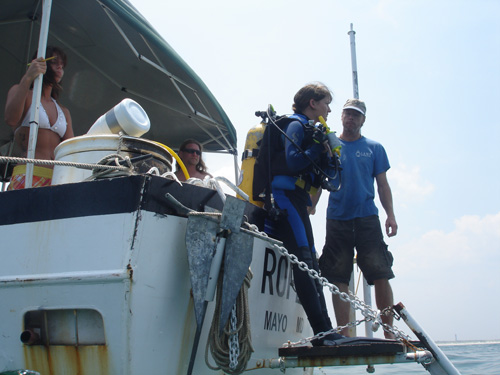

Graduate Student Supervisor Rachel Horlings, a PhD student from Syracuse University, launches herself into the water to dive on the wreck of an unknown sailing vessel. Students from all over the U.S. have traveled to America’s oldest port to participate in the 2009 LAMP Field School. Our primary objective is to excavate this sunken ballast pile in an attempt to determine if it represents the remains of the Confederate privateer Jefferson Davis.

Now that our students are out of “boot camp” the fieldwork begins. “In the field,” which in our case means in the waters offshore St. Augustine, is where they will learn archaeology by doing archaeology. Each morning begins at 6:00am when the entire crew meets at LAMP on the grounds of the St. Augustine Lighthouse & Museum. The first task is to load all of the gear that we need into trucks. Here LAMP volunteer and Field School student John “Tank” Brunswick helps load the truck with tanks–his specialty. We usually have two separate teams go out every day–a survey team to search for undiscovered shipwrecks, and a diving team to dive on and excavate the particular shipwreck site we are currently interested in.

While the tanks, dive gear, and other safety and archaeological equipment is loaded onto trucks at LAMP, we send a two-person team to go fetch the Roper, our diving vessel. Roper is kept at a private dock owned by local residents Bill Hutcherson and his family. They have generously allowed us to use their dock, which would cost us in the neighborhood of $1000 per month at a marina. Their dock is very close to the public dock at the Lighthouse boat ramp, which is where all of the students, gear, and boats meet for loading each morning. Here is the view of Salt Run looking south from the public dock, with Roper on its way.

One of the nice things about waking up so early are the sights which we normally sleep through. Here are some great early morning images of the Lighthouse taken from the boat ramp.

Once the Roper has arrived at the Lighthouse boat ramp dock, the loading begins–tanks, bags of dive gear, dredge pumps, dredge hose, the crew box full of archaeological supplies, jugs of water, line, buoys, all are passed over the gunwale in a mostly well-coordinated effort.

With lots of students in the field school there are many hands and the loading goes relatively fast. Some items, like this 40′ length of dredge hose, are large and unwieldy . . .

. . . which can lead to some interesting maneuvers on the dock and boat.

Once all the gear is loaded, Roper departs the dock. It doesn’t take long for the students to find one of the more enjoyable places to stow themselves away for the hour-long ride to the site. From left to right is Kaia Brown, Megan Staley, Honora Sullivan-Chin, Wendy Drennon, Chris Borlas, and Shelly Gray. Visible inside the cabin at the helm is Sam Turner, LAMP Director of Archaeology and our captain for the day.

Because the survey team is not going out today, due to a problem with our sub-bottom profiler, we have requested that LAMP’s newest vessel, the recently donated RV Desmond Valdes, join us for an hour or two to help us set our three-point anchoring system (and to bring us some extra fuel for the dredge motor, which we forgot to load).

In a three-point mooring system, we are anchored by our bow anchor as usual, but also use one anchor of the port stern and one off the starboard stern. Three anchors holds us pretty well in one place, despite winds and tides which change throughout the day. This is critical when we have hoses (hookah hoses, dredge hose, water pump hose) from the boat going down to the divers below. We direct the Desmond Valdes to take and anchor out and guide them as they position it for us in an appropriate spot.

Each of the students gets a “fam dive” on the site. This is a familiarization dive, necessary in order to orient themselves to what is a new site in dark, low-visibility conditions. Here Shelly prepares to enter the water for a dive. Sam is assisting her on the swim platform, while Chuck (who is serving as Dive Supervisor for the day of diving) and Kaia (who is acting as Timekeeper) look on.

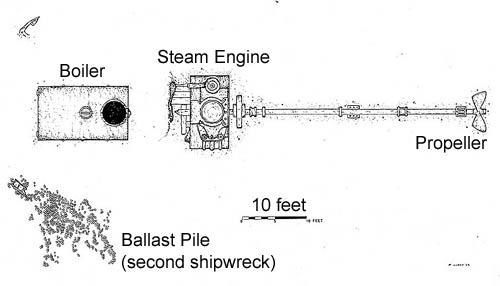

The site we are diving on is unique in that it is the final resting place of two individual shipwrecks. The more prominent of these is a massive steamship, with its boiler, engine, and propeller protruding up from the seafloor. In addition, there is a small ballast pile located just west of the boiler. This pile of rocks, and the wooden timbers preserved beneath it, is all that survives of a sailing ship of unknown date and identity. It is this vessel which we are postulating may be the Confederate privateer Jefferson Davis, lost in 1861 on the “North Breakers.” The North Breakers were located just north of the 19th century channel entrance and these two wrecks (undoubtedly along with many others) lie within the right spot. In 2007 LAMP and Flinders University investigated this double shipwreck site and you can read more about it here. This year’s strategy will focus on a meter-wide excavation trench that will cut across the ballast pile from one side of the hull to the other. We have laid in a gridded trench which will served as a guideline for our excavating divers and we plan to first remove exposed ballast from each 1 meter by 1 meter unit, and then excavate sediments using a suction dredge.

We are not the only ones interested in this shipwreck site. A sea turtle has been hanging out with us for a few field days. On the other hand, maybe he’s more interested in us than the wreck, and he does seem to like to inspect our anchor line in the water. Notice that in addition to the barnacles on his back, he has a wad of mud on his head. Like our divers, his activity on the bottom sends up plumes of mud visible to us on the surface. Also like our divers, activity that stirs up the mud fluff layer on the bottom decreases our visibility, which doesn’t seem to bother him at all. The vast amount of mud on our site and the surrounding seafloor is a by-product of the extraordinary torrential rains we suffered through in May of this year. They flushed an immense quantity of mud from the inland waterways out through the inlet.

Honora waiting for her buddy on the surface before her next dive.

Wendy is serving as safety diver for this dive. As such she is ready to enter the water at a moment’s notice if the Dive Supervisor commands her to do so. We follow strict scientific diving safety guidelines on every LAMP project.

On the subsequent dive, Wendy switches from safety diver to working diver. The visibility has steadily improved over the first three diving days of the field school. Today it is what we would consider exceptional, though only on top of the boiler and steam engine, which are of course higher above the muddy bottom. On a site like this, whenever you have a bit of visibility it is important to take advantage of it to check your air gauge. Over these first three days, our student divers have successfully oriented themselves to the wreck site, learned to deal with a low visibility working situation, recorded a profile or cross-section shape of the ballast pile directly along our excavation trench, and have begun to remove ballast stones from the trench.

Things have also been busy on the surface. Since we will soon be dredging we want to deploy and troubleshoot our dredge. Here the dredge hose is being lowered into the water.

This dredge is powered by a 9 horsepower water pump. This particular dredge system, along with a second powered by an 18 horsepower pump, is on long-term loan to LAMP by the Archaeological Research Cooperative. Maintenance on machinery that operates seasonally in a salt water environment is always problematic, which is why we are so excited that upon assembling the various hoses and running the motor that everything works!

Another motor that will be droning on for much of our time offshore is the hookah. This is a low-pressure compressor that can send air down to 1 to 5 divers at a time via a long flexible hose and standard scuba regulator. Our system is an Air Line by Joe Sink and as a rugged, reliable hookah for working divers we find it to be a fine system. One great advantage of the hookah for our divers is that even in the low visibility waters where gauges cannot be read, air management becomes much less critical, as each diver has an unlimited source of air as long as the hookah is running. If the hookah fails or runs out of gas, the diver simply switches to a scuba tank on his or her back.

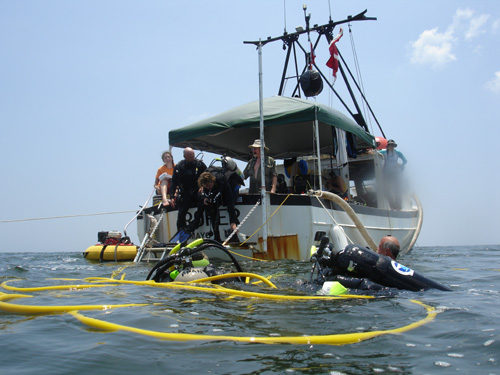

A potential disadvantage of the hookah is that the divers are tethered to a fixed point and are therefore less mobile. This is not necessarily a disadvantage if your divers are meant to be in one spot the entire dive such as during an excavation, and the tether also means that they are directly connected to the boat (a nice benefit when in low vis waters). On the other hand, this system does entail lots of hoses in the water, which can always constitute an entanglement hazard. It is usually easiest to have two divers in the water on hookah, and any additional divers working on scuba.

A multitude of hoses and lines in the water, along with the constant loud drone of machinery on the surface, are simply occupational hazards for the underwater archaeologist. Tending a line in this picture is veteran science diver Steve Resler, an underwater videographer from Pepe Productions here to help shoot a documentary on our search for the Jefferson Davis.

Another task that occupies our divers for the first few days of diving is the making of ballast lift boxes. We construct these by lining a standard milk crate with window screen, attaching a lead weight to the bottom to prevent them from floating when empty, and attaching two polypro line lift handles. These are used by divers on the bottom to fill with ballast stones recovered from a particular unit in our excavation trench.

Once a diver has completely filled a crate with ballast stones on the seafloor, he or she uses a lift bag (like the one pictured here behind Rachel) to help move the heavy box. A full box of rocks might weigh between 70 and 90 lbs or so. The diver attaches the empty lift bag, and slowly fills it with air. Too much air may cause the bag to skyrocket dangerously to the surface, so this is a delicate operation, and our lift bags have dump valves so it is easy to vent air from the bag if it is providing too much lift.

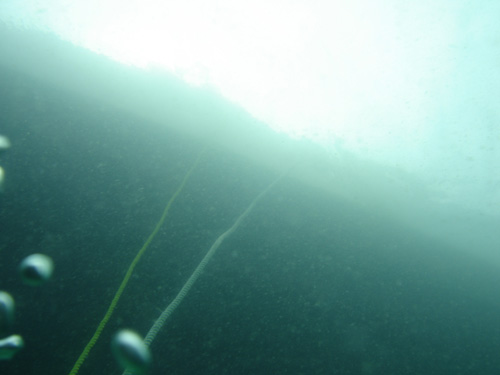

When the bag and rock box are close to neutral buoyancy, the diver swims it along a travel line on the seafloor to the pre-arranged lift station. This is directly below the side of the Roper at which we have attached a line and pulley to the mast, so its position changes slightly every day and has to be re-established each morning. A buoy has been dropped here, and the lifting line along with empty boxes can be attached to the buoy line and thus dropped down to the divers so that it lands at the same spot each time. The diver deflates and disengages the lift bag, attaches the box of rocks to the dropped lifting line, and then signals with two mighty tugs on the buoy that another load of rocks is ready to be hauled up. This is a view looking up at the buoy line and lifting line from below (not on the bottom where it is too dark to see, but from mid-way in the water column).

Up above, Megan and Sam haul on the pulley line . . .

. . . while Tank and LAMP Archaeologist and Logistical Coordinator Brendan Burke haul the box up . . .

. . . and over the gunwale.

Each box of rocks is tagged so that we can keep track of which meter square unit it was retrieved from. We will be transporting all ballast stones back to LAMP headquarters where they will be counted and weighed. A sample will be taken of these for analysis, and then the vast majority will be used to re-bury the site when we are finished with our excavation and need to fill in the trench.

At the end of our first week of diving, we have a special treat lined up for our students. We have been invited by fellow archaeologist Mike Murray for a special field school cruise aboard the schooner Momentum, docked here in St. Augustine. What a fabulous way to spend a Friday evening! The students have a chance to learn the ropes or just enjoy a beverage, dinner, and the sunset over the water.

What a great way to end the first week of Field School!