Friday was an exciting day! LAMP archaeologists joined a team of St. Johns County scientists to recover a 20-ft long, 100-year old historic dugout canoe from the alligator pit at the St. Augustine Alligator Farm. The boat had been sitting on the ground, exposed to the elements and to the activity of large alligators (one of which made her nest against the boat) for several years. We visited the boat the Monday before, and observed that it was clearly suffering heavy deterioration, which is why Alligator Farm officials were happy to trade it to the St. Augustine Lighthouse in return for another boat, a historic flatboat replica made by the volunteers at LAMP Boatworks.

Accompanying us was a reporter and photographer from the St. Augustine Record, which ran a great front-page story on the boat rescue the following day.

St. Johns County Archaeologist Robin Moore and LAMP archaeologist and conservator Christine Mavrick spent some time recording the boat several days before the move.

The story of this boat began back in 2005, when the owners of the Alligator Farm discovered it in a St. Augustine antique shop. They thought it would lend a great “Old Florida” look to the alligator pit, and also serve as a barrier from the gators which their trainers could use during the daily shows that take place in the pit. At that time, Alligator Farm staff contacted St. Johns County Archaeologist Robin Moore, a former LAMP archaeologist and current LAMP Research Associate. Robin very enthusiastically investigated the boat, quickly realizing that this was a one-of-a-kind St. Augustine treasure and worth spending some time to properly record–even if that did mean braving the dangers of an alligator pit!

This photograph was taken around the turn of the 20th century somewhere in the vicinity of St. Augustine. It shows two shapely dugouts, one of which appears to be virtually identical to the Alligator Farm Logboat. Compare the central boat in this picture with the Alligator Farm logboat in the picture above. Photograph courtesy of the St. Augustine Historical Society.

During his research, Robin came across the historic photograph above, which depicts a St. Augustine logboat which bears an uncanny resemblance to the one he was studying. This suggested to him that this boat represents a style unique to St. Augustine and dating to the late 1800s or early 1900s. In fact, this boat may be the only one left of its kind, and is thus very significant to the maritime history of our nation’s oldest port.

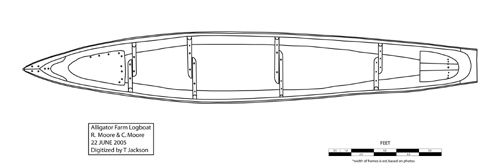

Plan view drawing of the Alligator Farm Logboat by Robin Moore (digitized by Tim Jackson).

The hull of this boat was carved out of a single cypress tree trunk, hence the names “logboat” or “dugout.” This type evolved from the Native American dugout which was universally used throughout the Americas, and also from a long-standing tradition of dugout boatbuilding brought to this area by enslaved Africans. The third element to this boatbuilding style are the techniques introduced by European colonists. This mix of styles modified a design that was thousands of years old through the use of iron tools and introduced features such as frames, oarlocks, thwarts, and a breasthook in the upper bow. The flat bottom of this boat, along with the squared off stern (with its hydrodynamic “wineglass” shape) and high sides created a swift, maneuverable vessel with increased stability and capacity. Without the need for sawn hull timbers and using minimal metal fasteners, this type of vessel was convenient to build in a colonial or frontier situation, very durable, and well-suited for river traffic. Widely used for transportation of people and goods, logboats such as this were common in St. Augustine from the earliest Spanish colonization through the dawn of the 20th century. The fine shape of this hull along with the ancillary features such as the railings, stern cap, interior frames, and breasthook indicate a highly refined St. Augustine logboat building tradition.

But this boat was in immediate danger–its contact with the wet ground and exposure to sun and rain caused severe deterioration and damage from insects and mildew. Each end displayed large gaping cracks that were rapidly getting worse. This unique vessel deserved to be cleaned up, conserved, fully recorded, and eventually put on display, and with the help of the Alligator Farm and St. Johns County staff, we intended to make this happen.

The first step was to dig out the dirt which had built up outside the hull, as well as the dirt accumulated in the interior. We did this very carefully with shovels and trowels, making sure not to add any modern tool marks to the hull which might hamper our later analysis of its construction. We also slid a series of bedsheets under the hull at evenly spaced locations, which we would use as lifting cradles to raise and move the boat when the time came.

All the while, of course, we had to keep our eyes open for alligators. Whenever any became too frisky, Alligator Farm Director and General Manager John Brueggen was there with his big stick to ward them off.

Under the direction of Lighthouse Director of Collections Kathleen McCormick and LAMP archaeological conservator Christine Mavrick, the stern end of the vessel was bound up with strapping and foam to protect it during the move. The extreme cracking here made it considerably fragile.

Once the logboat was stable and ready to be moved, we brought the new replacement boat into the pit.

This vessel is a replica of a barca chata, Spanish for “flat boat,” which the volunteers at LAMP Boatworks built and launched almost exactly one year ago. This type of vessel, commonly called a flat or flatboat, was–like the dugout–very common throughout the colonial and later historical periods.

It is also an appropriate “Old Florida” boat for the Alligator Farm, as evidenced by this turn of the century engraving showing a similar flatboat being used on the St. Johns River for alligator hunting.

Finally it came time to move the logboat. With many hands–LAMP staff and volunteers, St. Augustine Lighthouse & Museum staff, and St. Johns County staff–the boat lifted easily enough.

We carefully made our way to the exit gate . . .

. . . and pass the boat to those waiting up above . . .

. . . while those still in the pit lift the hull up in order to pass it through the gate . . .

. . . and place it safely on the walkway outside. Job well done! We even got a round of applause from the crowd of enthusiastic visitors.

Back in the pit, we arrange the barca chata in place, just in time for the 11:00 alligator feeding. Good thing we made it out in time!

Meanwhile, outside the Alligator Farm’s service gate, we successfully load the logboat onto a trailer (on loan to us from the Guana-Tolomato-Matanzas Research Reserve).

The boat is carefully wrapped in sheets to protect it from direct sunlight, and secured on the trailer with foam, towels, straps, line, and supporting lumber underneath the protruding end. Once safe and secure, we proceed in a slow motorcade from the Alligator Farm to LAMP’s Field House outside of town. In addition to student housing during our field school, this property has several outbuildings, including a large barn which serves as our Conservation Annexe.

The trailer is parked underneath a tin roof overhang outside the Annexe to keep the logboat in the shade while we build several sawhorses. These will be used to store the boat off the floor so that we can fully access it on all sides during the cleaning, conservation, and recording process.

Once they are ready, we move the boat one last time.

And finally the boat is safe on its new sawhorse supports.

Now we can for the first time observe the condition of the flat bottom of the hull . . .

. . . while at the same time access the interior with relative ease. LAMP archaeological conservator Christine Mavrick begins the cleaning process immediately.

And of course how could we end such a day without a group photo? Pictured here, starting on the left and moving clockwise, are Lighthouse Director of Collections Kathleen McCormick, LAMP archaeological conservator Christine Mavrick, LAMP volunteer Lindsay Jones, LAMP Director of Archaeology Sam Turner, LAMP remote sensing technician Kendra Kennedy, LAMP Director Chuck Meide, Lighthouse human resources specialist Kyle Worrell, LAMP archaeologist Brendan Burke, and LAMP volunteer John “Tank” Brunswick. Not pictured are LAMP volunteer Debbie Cox (the photographer), LAMP volunteer Nick McCauliffe, Lighthouse maintenance director Bruce, LAMP volunteer boatbuilder Jim Gaskins, St. Johns County Archaeologist Robin Moore, St. Johns County Land Manager Amy Gilboy Meide, and Alligator Farm Director and General Manager John Brueggen. Thank you to everyone for all of your hard work!