Lighthouses conjure up romantic images of windswept shorelines and the intrepid keepers who maintained the light through the night.

However, by the mid-20th century, technology conspired to eliminate the light keepers’ responsibilities. Electric bulbs replaced the glow of oil lanterns; electric motors made the clockwork mechanism that turned the lens obsolete. Photocells, like the kind you find on the tops of streetlights around the country, now turned the light on and off.

And in 1955, with the St. Augustine Lighthouse completely automated, there was no longer a need for nightly visits by the light keepers.

The Lamplighters

Despite the removal of light keepers, the U.S. Coast Guard still needed people to ensure the lights came on each night and perform routine maintenance. They called these people lamplighters. To fill these positions, the Coast Guard turned to those most familiar with the keeping of lighthouses: former light keepers.

The first lamplighter at the St. Augustine Lighthouse was a familiar face. David Swain had served as first assistant keeper from 1933 to 1944 before moving on to other lighthouses in Florida.

Swain was at the Lighthouse in 1936 and assisted in the electrification of the light. He also served when the keepers began assuming more responsibility for the growing number of buoys and lighted aids-to-navigation on the waters around St. Augustine. This experience with the electrified tower and buoys left Swain uniquely suited to serve as a lamplighter. In 1955, David Swain, already retired, became lamplighter in St. Augustine at the behest of an old friend who served as a Coast Guard aids-to-navigation officer in Miami.

In addition to his experience in electrified lighthouses, David Swain’s nearby home on Comares Avenue gave him a view of the light, which he checked was working from his front yard each night. He made a weekly trip up the tower to check the light and complete regular maintenance. The lighted buoys in the waters off St. Augustine also fell under his jurisdiction. He even helped paint the Lighthouse three times in those years. In 1968, David Swain’s retirement brought his role as the St. Augustine lamplighter to a close. As his last official act, he recommended his replacement, a man who had always told Swain he wanted his job, Henry Mears.

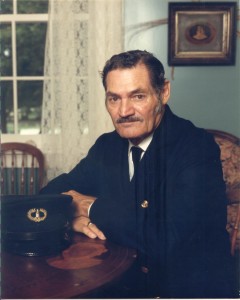

Henry Mears, clad in a light keeper’s uniform, in 1989

Henry Mears (“H.R.” to his friends) became lamplighter after a career in the Coast Guard that included service as far away as Alaska and saw him take care of the Cape Canaveral Lighthouse. His responsibilities were the same as David Swain’s before him: make sure the light is on every night, check everything once a week, and tend the buoys in the waters inland and off St. Augustine. Interviewed in 1978, for The Explorer, Mears mentioned that his job as St. Augustine’s lamplighter made his transition to retired life easier. As he said, “I didn’t miss the Coast Guard so much. I’m doing what I used to do…what I like best.”

Although he did not live on site like the light keepers did, Mears still had a few interesting incidents at the Lighthouse.

In 1986, Mears found the Fresnel lens damaged from a vandal’s bullets. He was also serving when the Keepers’ House caught fire, though he never lived in the house. Henry Mears served as lamplighter until 1989 when budget cuts forced his retirement and eliminated the lamplighter position at the St. Augustine Lighthouse.

Today, the St. Augustine Lighthouse & Maritime Museum carries on many of the activities performed by our lamplighters. We keep the Lighthouse operational, ensuring it continues to shine bright for the mariners who ply the waters off our city’s coast.

Paul Zielinski is Director of Interpretation for the St. Augustine Lighthouse & Museum. He received his master’s degree in Public History from the University of West Florida and joined the lighthouse family in 2011.