Compiled by James Smith

In the closing days of World War I, the world faced one of the worst pandemics of the modern era, the Spanish Flu Pandemic. The term Spanish Flu originated largely because the United States government did not want news of the disease to diminish the war effort, since the conflict was nearly won.

World War I ended with the armistice on November 11, 1918. However, Spain remained neutral in the conflict. Therefore, the reports of the deaths in Spain reflected flu victims and not war dead. Most people assumed the disease originated in Spain since the reported numbers were much higher there than other parts of the world.

Unfortunately, World War I provided the opportunity for the disease to spread rapidly. The first reports of the Spanish Flu hitting the front lines of the war took place in spring 1918. Scientists and historians still argue over the origin of the Spanish Flu. Many believe it originated in Kansas where soldiers trained for battle. When they left the United States and headed overseas, they inadvertently carried the disease to the world. By May 1918, fourteen of the largest training camps reported cases of the disease. The flu was a common occurrence in military camps, however by the summer, a newer and deadlier strain began to emerge and alarm medical personnel.

The Spanish Flu struck in two major waves. The first wave produced mild symptoms including a slight fever. Most soldiers did not consider the symptoms too grave and remained at the front or on duty. However, when the deadlier strain emerged, soldiers sought medical attention in the field hospitals along the front. As the numbers of sick increased, the military flew the infected to bases in the United States were special wards opened. As overcrowding was a natural outcome of the war, the illness made inroads very quickly into these hospitals and camps.

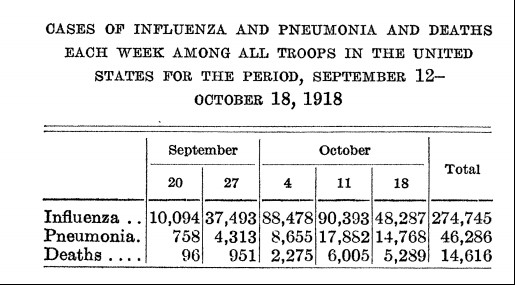

The chart above shows the speed with which the Spanish Flu spread through the American camps at home. The inclusion of pneumonia in the chart is an indication that the disease was a secondary infection of the Spanish Flu. In other words, if the Spanish Flu didn’t kill you, there was the risk that pneumonia would.

One of the other important aspects of the Spanish Flu is the average age of the victims. Normally, as with Coronavirus, those with weakened or compromised immune systems are the typical victims. However, with the Spanish Flu, the opposite was true. The disease triggered what is called a “cytokine storm;” meaning the body overreacted to the presence of a virus. In most humans, the body will direct immune cells to the areas where the virus is present. However, in some cases, the body produces an overabundance of cytokines (small proteins that are important in identifying foreign cells in the body). Overproduction of cytokines can seriously harm the patient and even result in death. The Spanish Flu produced such reactions. As a result, the largest victim demographic included people under the age of 65. Half of those affected were adults aged 20 to 40 years. The men fighting World War I fell largely into this age group, the perfect recipe for widespread death.

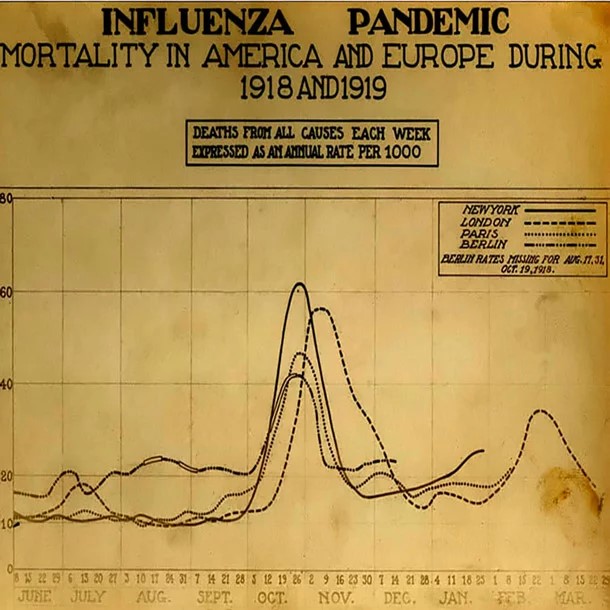

The worst months of the pandemic took place during October and November 1918 just as the war was coming to an end. As the soldiers began to return home, many of them brought the Spanish Flu with them. The disease tested not only the resolve of Americans but of the entire world as literally millions of people across the globe faced the double impact of war and disease.

(Note: stay tuned for another article focused on the impact of the Spanish Flu in America and within Florida and St. Augustine)