“After the surrender of Charleston in 1782, within two days no less than 16 vessels, bearing refugiés and their effects, went to pieces here and many persons lost their lives.”

– Johann David Schoepf, 1788

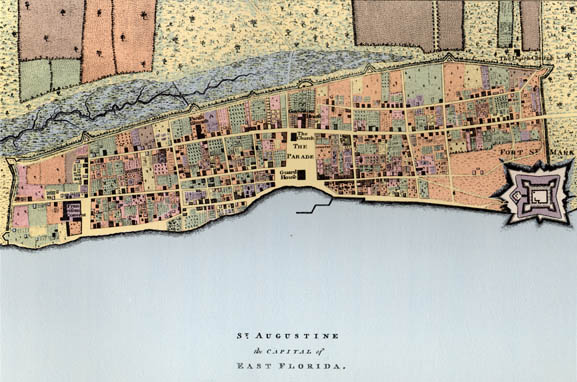

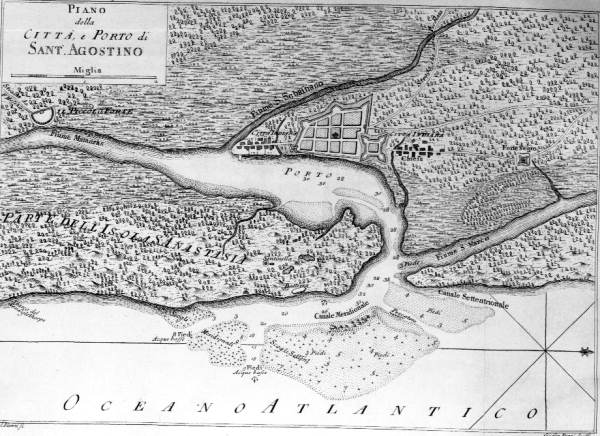

While the identity and exact date of the Storm Wreck remains unknown, the evidence uncovered to date suggests that this vessel was shipwrecked at the mouth of the St. Augustine Inlet in the late 18th century, possibly in the years immediately after 1780 when the American Revolution was coming to a close. This period was one of dramatic demographic and sociocultural change in St. Augustine, as the capital and primary port of East Florida would switch hands from British to Spanish control as a result of the war. Perhaps the most striking of these changes was a population explosion in St. Augustine due primarily to the influx of British Loyalists seeking refuge from the thirteen rebelling colonies. Archaeologists believe there is a distinct possibility that the Storm Wreck may indeed represent one of many ships full of Loyalist refugees that ran aground and came to pieces while trying to enter St. Augustine.

October 19, 1781 prompted the British government to begin negotiations

which lead to the end of the Revolutionary War. Image courtesy of Wikipedia.

After the fall of Yorktown in 1781, decisive battles gave way to backcountry skirmishes as peace negotiations influenced the remainder of the war years. The lives of British Loyalists were dominated by the question of evacuation. The British army still occupied New York City when the Treaty of Paris was initially signed in November 1782, but Savannah and Charleston were either fully evacuated or in the process. North American port cities formerly under British control emptied their inhabitants into the waters of the Atlantic, while the inland Loyalists clogged the back roads and trails near the borders of Canada and East Florida. Nova Scotia, Quebec, England, the Bahamas, the British West Indies, and Central America became ports of call for countless loyal emigrants. But many southern Loyalists looked closer to home.

Courtesy of the Florida Museum of Natural History.

In St. Augustine an unparalleled event took place during the post-Yorktown evacuation procedures. For most southern Loyalists the Canadian climate was presumed utterly unsuitable for planter society and the slave ownership that made them prosperous. Southern Tories saw East Florida as a sanctuary where they could rebuild their lives without leaving the warmer regions of the continent to which they were accustomed. In spite of this, a general pattern of evacuation after the war quickly developed as slave owning Loyalists sought the warmer climates of the Caribbean while those with few or no slaves went to Europe or Nova Scotia (Troxler 1981:21).

However, this was not the first time that Charleston and Savannah changed hands during the war. Even after Yorktown, most American Loyalists firmly believed that it was simply a matter of time before the United States became crippled economically and/or militarily. For a nation to successfully erect itself from colonial status was unprecedented in 1782. Therefore, southern Loyalists chose to remain close to their former land holdings in order to reclaim their property as quickly as possible, just as they had after previous evacuations during the war (Wright 1971:377). Most of these people had already experienced one forced evacuation—two, for those from Savannah who went first to Charleston in July 1782. The injustice that the war wreaked upon their lives took a heavy toll.

The increased flow of refugees from southern back-country fighting swelled the white civilian population of the colony to approximately 4,500 by late June 1782. The majority of this group came first to St. Augustine to register their presence with Governor Tonyn and receive their 500 acre homesteads. The Menorcans now living in St. Augustine (presuming no natural increase from 1777 to June 1782, for the purpose of erring on the side of caution) tallied at approximately 600. The majority of the black population of East Florida—approximately 4,000 total—were on the plantations, but many free blacks were living in St. Augustine (del Campo 1783). These numbers, though relatively small in appearance, were the measure for overcrowding mentioned up to this point. The dam was about to burst.

Courtesy of the State Archives of Florida.

From July 12–25, a deluge of over 7,000 Loyalists from Savannah and Charleston sailed into St. Augustine (Siebert 1929:7). Another 3,826 Loyalists came from Charleston by sea in late December (Siebert 1929:7). The overwhelming crush of humanity that befell the tiny capital of St. Augustine in short bursts is staggering, and yet the numbers listed here consist only of those refugees who arrived by ship. There is no means of knowing the number of refugees who drifted into the province on foot after June 1782, or the number of black refugees who sought shelter with the Seminoles and were never counted. This does not include the military or Indians who frequented the town.

With the entrance to St. Augustine impeded by a notorious sandbar, which gave the port its reputation as the most dangerous of all Britain’s Atlantic colonies, it is no surprise that a significant number of these incoming refugee vessels were wrecked. Indeed, in one incident in December 1782, sixteen ships loaded with Loyalists from Charleston came to grief while trying to enter St. Augustine (Schoepf 1911[1788]: 227-228). In another example that same month, Rattlesnake, the military escort for a fleet of at least 8 ships bringing Loyalists to St. Augustine, also ran aground and wrecked with four lives lost (Singer 1992:169). It seems quite likely that the Storm Wreck, which appears to date to this period, could represent one of the many refugee ships lost in conjunction with St. Augustine’s Loyalist influx at the end of the Revolution.

References Cited:

del Campo, Bernardo

1783 Observations on East Florida. Inclosure No. 1 in letter to Conde de Floridablanca, 8 June. Archivo Historico Nacional, Madrid. Estado, leg. 4246 Ap 1. In East Florida, 1783-1785, A File of Documents Assembled and Many of Them Translated, Joseph Byrne Lockey and John Walton Caughy, editors, 1949, pp. 117-127. University of California Press, Berkeley.

Schoepf, Johann David

1911 [1788] Travels in the Confederation (1783-1784). William J. Campbell, Philadelphia.

Siebert, Wilbur H. (editor)

1929 Loyalists in East Florida: The Narrative, vol. 1. Publications of the Florida State Historical Society No. 9, Deland, Florida.

Smith, Roger C.

2011 The Fourteenth Colony: Florida and the American Revolution in the South. Doctoral dissertation, Department of History, University of Florida, Gainesville.

Singer, Steven D.

1992 Shipwrecks of Florida: A Comprehensive Listing. 1st ed. Pineapple Press, Sarasota, Florida.

Troxler, Carolyn

1981 Loyalist Refugees and the British Evacuation of East Florida, 1783-1785. Florida Historical Quarterly 60(1):1-28.

Wright, J. Leitch

1971 Lord Dunmore’s Loyalist Asylum in the Floridas. Florida Historical Quarterly 49(4):370-379.

This essay was written by Dr. Roger Clark Smith and Chuck Meide in 2012. Other than the introductory and closing paragraphs, written by Meide, it is largely based on Dr. Smith’s doctoral dissertation (2011:271-280). Dr. Smith is a professional historian and LAMP Research Associate, whose research interest focuses on the history of East Florida during and immediately after the Revolutionary period.

All text and images, unless otherwise noted, are copyright Lighthouse Archaeological Maritime Program, Inc. We extend permission to scholars, students, and other interested members of the public to use images and to quote from text for non-commercial educational or research purposes, provided LAMP is acknowledged and credited. If there are any questions regarding the use of LAMP’s work, please inquire at LAMP@staugustinelighthouse.org.