People have hunted whales around the world for thousands of years, primarily for meat and blubber. In America, the practice really took off in the colonial 18th century and hit its peak in the mid-19th. The most lucrative product at this point was whale oil, derived from boiling down blubber or harvesting the head of sperm whales. As the American industry grew and expanded, so did the whaling practices and technology, which is where our conservation topic comes in today.

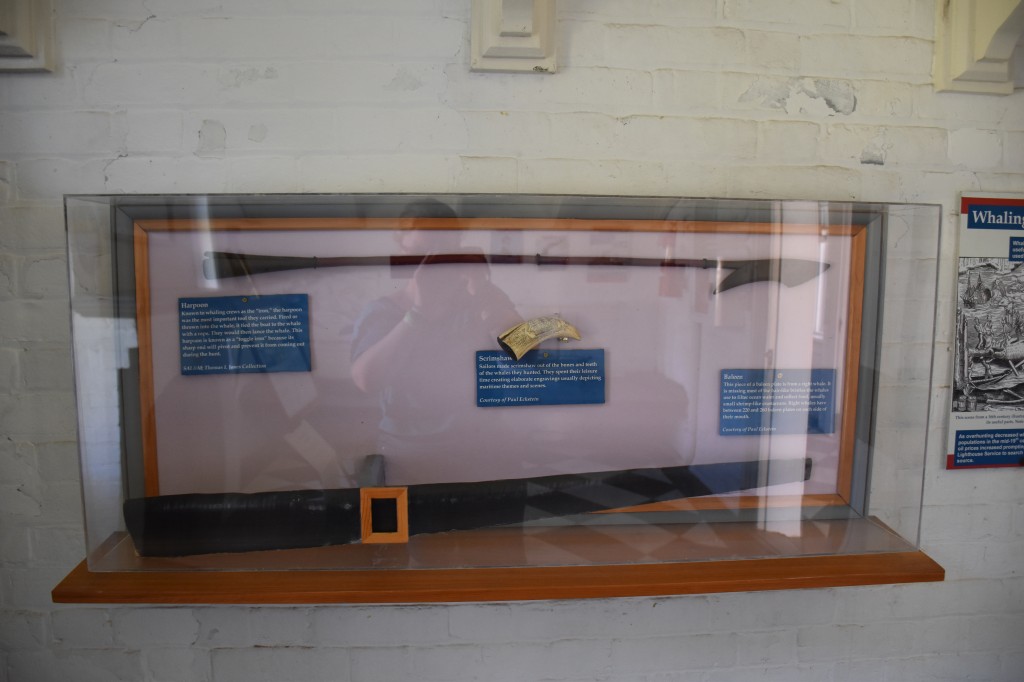

There is a harpoon that is part of an education collection in the oil house. While the whaling industry was never directly involved with the St. Augustine Lighthouse and Maritime Museum, it was still a part of the lighthouse world. The refined whale oil was a highly sought after commodity used for lantern fuel and many lighthouses were lit in such a manner.

In order to get the whale oil, crews had to somehow hunt and harvest them. Early harpoons were made of wood, bone and stone. They were thrown or shot into the whale and attached to a floating object. The idea was to tire the whale out until the hunters could finish it off. Eventually, as larger whale species were targeted, larger, deadlier and more durable harpoons were created. Our particular artifact is an interesting variation that became a gold-standard for harpoons. The style is referred to as a “standard improved toggle” harpoon. It is credited as being designed by Lewis Temple, a freed slave and blacksmith. He opened a shop in the whaling community of New Bedford around 1845 and his style became incredibly popular, partly because he never patented the design and since it was so effective. This does make it difficult to definitively identify our harpoon, though, as many manufacturers made and sold them.

The small head is designed to cut and penetrate deep into the whale skin easily. The rear of the head has a sweeping barb that holds the harpoon in place. The ingenuity of Temple’s invention, though, is a pivot in the center of the head. When the harpoon is pulled back, the barb turns outward and rotates the head into a T-shape, locking it in. Another clever bit of engineering is the long, skinny shaft. The cast iron used in the harpoon is strong, but flexible, so that it can twist and bend after insertion and during the pursuit.

The conservation for the harpoon was very easy and unobtrusive since the artifact does not actually belong to the St. Augustine Lighthouse and Maritime Museum. I did not want to add any chemicals or sealants that would be difficult for a future curator or conservator to remove, should the need arise.

Overall the condition of the metal was pretty good. There were a few spots here and there on the bare cast iron that showed signs of corrosion. These were exclusively on the head and base of the shaft. The paint on the shaft of the harpoon, however, looked good and did not need any treatment.

I started by carefully brushing off the rust and corrosion product from the iron using a toothbrush. For the more stubborn spots I used a small wire wheel and bit of steel mesh. When the metal was clean, I then covered the exposed parts with a light coat of air tool oil to penetrate and prevent additional oxidation. The oil has few additives that would strip the iron or gum up the surface while it dried. After the oil, I then sealed both ends of the harpoon using heated microcrystalline wax. The molten wax is able to seep into all the pores of the metal and seal the surfaces from exposure to the atmosphere.