Located in New Jersey, at the mouth of New York Harbor, the Sandy Hook Lighthouse was visible to immigrants on their way to Ellis Island (courtesy of the Library of Congress).

The connection between lighthouses and immigrants to the United States is inescapable. Dotting the coastline, the bright beacons were often the first sight of land for many people hoping to find opportunity and freedom in a new land. For some of these immigrants, their chance at a new life was closer than they may have thought. The ranks of lighthouse keepers saw a steady increase in foreign-born keepers through the 19th century.

Though subject to peaks and valleys, immigration into the United States steadily increased through the 19th century, peaking in the early 1880s. Immigrants in the second half of the 1800s arrived primarily from Europe, with Germany, Ireland, the United Kingdom, Sweden and Norway leading the way. Some immigrants to the United States in the 19th century found jobs doing the same work they did in the maritime industries of their home countries. Many had experience as sailors, fishermen, and harbor pilots.

The Official Register of the United States

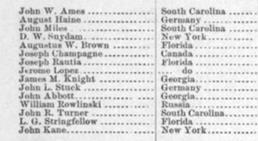

By the 1880s, many of these foreign-born maritime workers had joined the ranks of US lighthouse keepers. Starting in 1816, the US government began publishing a yearly Official Register of the United States, which listed all employees and agents of the federal government, including lighthouse keepers. Later volumes decline to include a full register of US lighthouse keepers, due to the large number of keepers. Early volumes, however, list all keepers, their post, salary, where they joined the Lighthouse Service, and the country in which they were born.

The lists in each volume of the Official Register serve as a kind-of microcosm of American immigration and lighthouse proliferation. The 1819 volume, one of the first published, lists only 57 keepers in the entire country, owing to the relatively few lighthouses at the time. Among this number, there appear no foreign-born keepers, also in keeping with the low number of immigrants at that time. From here, the number of lighthouses and immigrants grew steadily throughout the 19th century.

The 1889 volume of the Official Register shows where these European immigrants found the best opportunities to break into the business of keeping lighthouses. US lighthouses were separated into geographical districts. The Official Register lists keepers by district, showing some interesting patterns regarding immigrant keepers and geography. Some lighthouse districts, especially those in the Southeast, Great Lakes, and West Coast had a much larger percentage of keepers who were born outside the United States than others.

In 1889, Official Register lists 63 total keepers in the Sixth District of the Lighthouse Service. 31 of these keepers were born in a foreign country. Almost half of all keepers from the Cape  Fear area of North Carolina to Jupiter Inlet Lighthouse halfway down Florida’s Atlantic Coast were immigrants. This district includes the St. Augustine Lighthouse. The Sixth District appears to have one of the highest percentages of foreign-born keepers, though they are also well represented in other districts as well.

Fear area of North Carolina to Jupiter Inlet Lighthouse halfway down Florida’s Atlantic Coast were immigrants. This district includes the St. Augustine Lighthouse. The Sixth District appears to have one of the highest percentages of foreign-born keepers, though they are also well represented in other districts as well.

The breakdown of immigrant lighthouse keepers in the Sixth District in 1889 is as follows:

- 8 from Sweden

- 5 from Ireland

- 4 from Norway

- 4 from Germany

- 2 each from Denmark, Canada, and the West Indies

- 1 each from England, Prussia, Russia, and Austria

In the 1889 Official Register, the keepers listed at the St. Augustine Lighthouse, Joseph  Rantia and Jerome Lopez, were from Florida. Although they were both born in Florida, as we’ve discussed before, they were descendants of Menorcans brought over to British Florida as indentured servants in the 1760s. The list of Sixth District keepers also contains a few foreign-born men who eventually would make their way to the St. Augustine Lighthouse during their careers.

Rantia and Jerome Lopez, were from Florida. Although they were both born in Florida, as we’ve discussed before, they were descendants of Menorcans brought over to British Florida as indentured servants in the 1760s. The list of Sixth District keepers also contains a few foreign-born men who eventually would make their way to the St. Augustine Lighthouse during their careers.

Immigrant Keepers at the St. Augustine Lighthouse

William Rowlinski was head keeper at the Mosquito Inlet Lighthouse (now known as Ponce Inlet Lighthouse) at that time. Rowlinski was born in Russia and began his lighthouse career as Second Assistant Keeper at the St. Augustine Lighthouse in 1883 before moving on to several other lighthouses including ones at Cape Romain and Georgetown, SC in addition to Mosquito Inlet.

The 1889 Official Register also lists Peter Rasmusson, born on the island of Falster, in Denmark, as First Assistant Keeper at Tybee Island Lighthouse outside Savannah, Georgia. Finding his maritime beginnings as a sailor at a young age, Rasmusson eventually became the longest tenured lighthouse keeper at the St. Augustine Lighthouse. He arrived in 1901, taking over for Joseph Rantia, and serving for 23 years. In 1924, Rasmusson retired, paving the way for another foreign-born keeper to take his place.

John Lindquist was born in Sweden and became a globetrotting sailor at the age of 15. After circling the globe twice, Lindquist jumped ship during a voyage to Galveston, Texas and swam to shore. From then on, in his words, “I was American.” He spent about eight years as First Assistant Keeper at the St. Augustine Lighthouse during his career then took over for the retiring Peter Rasmusson in 1924 and served for a little over two years as Head Keeper. Upon his retirement in 1926, the St. Augustine Evening Record reported that Lindquist “received the distinctive honor of being the keeper of the finest station in the lighthouse district, for which he has received the efficiency pennant and star of efficiency…given only to those who have the best kept station.”

Just as they have to the entire nation, immigrants contributed to the successful operation of US lighthouses, including the St. Augustine Lighthouse. They carried oil, trimmed wicks, and polished lenses alongside American-born keepers. They made sure ships of all nations could navigate US shores safely. And they kept the coastlines safe for their fellow immigrants’ arrival to their new home.

Paul Zielinski is Director of Interpretation for the St. Augustine Lighthouse & Maritime Museum. He received his master’s degree in Public History from the University of West Florida and joined the lighthouse family in 2011.