Earlier this year, St. Augustine Lighthouse & Maritime Museum Archaeologist and Maritime Historian Brendan Burke traveled to Virginia to assist in research on a Civil War shipwreck. The following is excerpted from his report on the wreck.

Guns on the Potomac

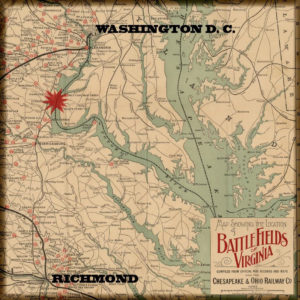

Washington D.C. was never far from action during the American Civil War. Almost immediately after war was declared in 1861, a struggle erupted between U.S. and Confederate forces to control strategic points throughout the Chesapeake Bay and its tributaries. Confederate forces quietly placed heavy artillery along the Virginia banks on the Potomac, strategically placed on commanding heights.

Washington D.C. was never far from action during the American Civil War. Almost immediately after war was declared in 1861, a struggle erupted between U.S. and Confederate forces to control strategic points throughout the Chesapeake Bay and its tributaries. Confederate forces quietly placed heavy artillery along the Virginia banks on the Potomac, strategically placed on commanding heights.

By the fall of 1861, batteries were ready for duty at Shipping Point, Possum Point, Freestone Point, and Cockpit Point. Washington was cut off by water, and the navy from one of its most important naval yards. Confederate guns controlled river line access up and down the river, only on a moonless night could ships pass the blockade.

The reality of strategic isolation and embarrassment spurred the U.S. Navy into action. Assaults were launched against the Confederate batteries In September of 1861 a battery at Freestone Point was engaged by the screw sloop Seminole and gunboat Jacob Bell but without effect.

In January of 1861, a second assault was led by Anacostia and Yankee on Cockpit Point. The action was largely inconclusive and Yankee suffered the only damage when ball passed through her hull and wounded a sailor. By March of 1862 the Potomac Blockade was entering its seventh month. A third operation was launched, again by Anacostia and Yankee, but with the addition of a landing party.

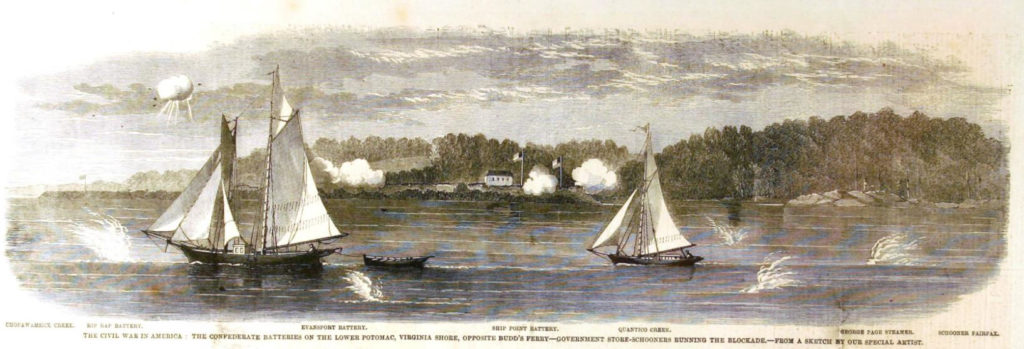

A lithograph from Harper’s Weekly depicting Confederate batteries at the mouth of Quantico Creek. Ships running the blockade of Washington D.C. are shown under fire. For five months, the nation’s capital was cut off from all waterborne access.

Confederate General Joseph Johnston was, at this time, pulling troops back due to a well-publicized and pending assault on Richmond by U.S. Gen. George McClellan. This withdrawal of forces coincided with the March assault, effectively disarming Confederate batteries along the Potomac.

During the Confederate withdrawal, two heavy cannon were loaded into a commandeered boat. Their destination was the railroad wharf at Aquia Creek, infrastructure to move the guns to another battery. However, according to John Thomas Scharf, a soldier with the 1st Maryland Artillery, advancing U.S. forces caused the Confederate troops to scuttle their vessel almost immediately after getting underway. Swimming ashore, they escaped and prevented the guns from falling into Union hands.

Departing Confederate artillerists unsuccessfully attempted to destroy one of their largest guns, a 150-lb Parrot rifle, by double charging, double wadding, packing the bore with clay, and lighting a bonfire underneath. Other heavy guns were pushed over the bluff and into the muddy riverbank. Some of the largest guns emplaced were only intimidating in size and were referred to as ‘Quaker’ guns. Hewn from oak trunks, painted black, and placed amidst real ordnance in the batteries, these guns successfully led Union observation balloons to believe that Confederate batteries were stronger than advertised.

Archaeology On-Site

During a multi-year search for and recordation of the Confederate gunboat City of Richmond (ex George Page), the Institute of Maritime History (IMH) deployed a sidescan sonar survey in Quantico Creek to help locate wreckage. As part of the 2011 survey a target was identified outside of the creek’s mouth that was not the City of Richmond but appeared to be historic. No further investigation was possible at the time due to time constraints.

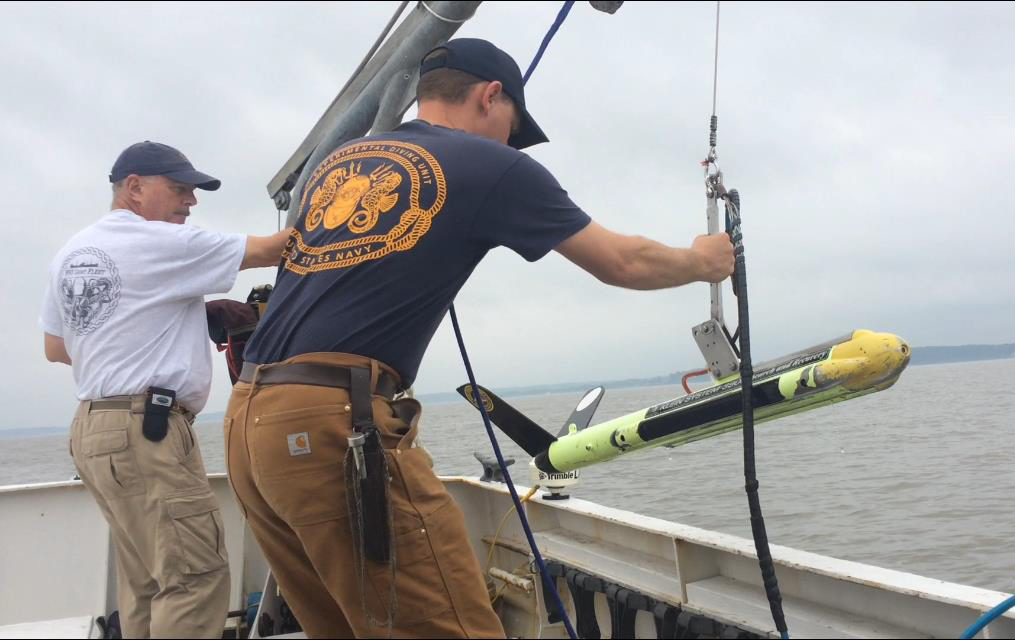

During the spring of 2016, IMH teamed with the Lighthouse Archaeological Maritime Program ( LAMP) to return to the unidentified target located in 2011. In late May, a survey team departed Tall Timbers, Md., aboard the Institute’s research vessel Roper for a three day survey and diver investigation.

Working closely with the Maryland Historic Trust (MHT) and the Naval Historic and Heritage Command (NHHC), the IMH team deployed a marine magnetometer and sidescan sonar over the target as the first phase of investigation.

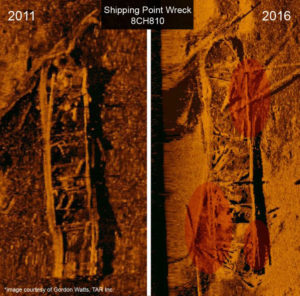

Above: Sidescan sonar images from 2011 and 2016 show areas of significant deterioration, overshadowed in red. Below: The magnetic signature of the wreck is plotted over the sonar image.

Results of the remote sensing survey indicated that wreckage was still largely intact, exposed on the river bottom, and had magnetic characteristics indicative of a large ferrous mass. Magnetic contouring also indicated the location of the magnetic source in relation to the wreck, enabling dive teams to pinpoint search areas.

Diving took place over two days. Conditions for divers were poor, with less than one foot of visibility at most times.

The wreck is situated in more than twenty feet of water, a depth at which all ambient light was lost during the survey. Prior to diving, the region had experienced over two weeks of continual rain, which added to visibility problems on-site.

However, dive teams were able to establish the exact location and orientation of the wreck, take basic measurements of timbers and determine integrity of the hull structure.

During a reconnaissance dive, I was able to see hull timbers during brief periods of clear water. With the aid of a powerful light, timbers in almost perfect condition appeared out of the black gloom. Fasteners, pieces of chain, and even tool marks were readily apparent.

During a reconnaissance dive, I was able to see hull timbers during brief periods of clear water. With the aid of a powerful light, timbers in almost perfect condition appeared out of the black gloom. Fasteners, pieces of chain, and even tool marks were readily apparent.

Groping my way slowly along the hull in the pitch black, I was excited to feel the hull’s exterior planking, a cap rail still in place, the boat’s frames and ceiling timbers. Rarely does an archaeologist get to work with such an intact vessel. Slowly working my way over tangled planks, timbers, and debris, I remained vigilant to not disturb the wreck and also not get tangled in it.

Recovering data from the wreck was a slow task. We were not permitted to perform excavations or sediment disturbance. Similarly, the project operated under a voluntary non-recovery agreement with MHT and so no artifacts were disturbed in the course of our fieldwork. Nonetheless, by the end of the day, despite a strong current and almost no visibility we had some basic measurements and estimations of the vessel.

More and more, our findings pointed towards the hypothesis that this was a Civil War-period canal boat used to evacuate Shipping Point batteries. During the second day of diving, project divers encountered similar underwater conditions with the addition of a gale warning.

For a while it looked like the project would have to be cut short due to weather. However, a final dive team was deployed to measure the hull width. I joined them to investigate the area where the magnetometer and sidescan sonar showed a cannon-like target. Descending once more into the ink I turned on my light. Covered in a fine mud, any movement near the bottom stirred up a thick cloud of sediment that would take minutes to dissipate.

Expecting no visibility, I stuck to my dive plan, which was based on one compass measurement and two measurements that I could easily estimate with my arms. Once on the bottom, I felt around in the dark, feeling for the wreck. Finding it quickly, I followed a series of timbers and figured out where I needed to go to reach my destination.

Working in the dark, you have to periodically stop and think about where you are, re-checking your surroundings by braille to make sure you are where you think you are. Almost immediately, my left hand felt an upward-protruding cylinder about one hand long and almost as thick. Following it down, it connect to a much larger curved surface.

Following outward with fingertips only, the convex surface curved gracefully away in two directions. My brain told me to jump to conclusions but my training told me to learn more. Taking out a folding-rule, I measured the initial cylinder at 7.5 inches in diameter and 8 inches in length, the perfect dimensions for a trunnion on a large cannon, specifically a IX (9”) Dahlgren.

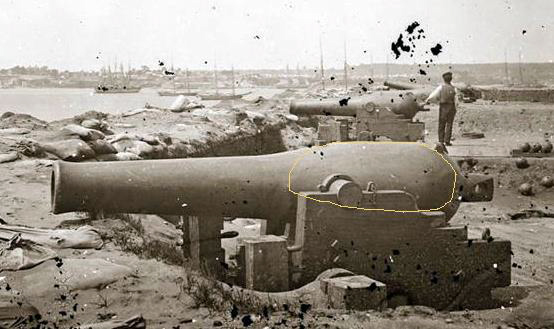

This IX (9”) Dahlgren was a type of heavy cannon commonly used for coastal defense. Note the orange oval superimposed on the gun’s barrel, showing what was exposed on the Shipping Point Wreck’s ordnance during the 2016 survey. Images courtesy of the Library of Congress.

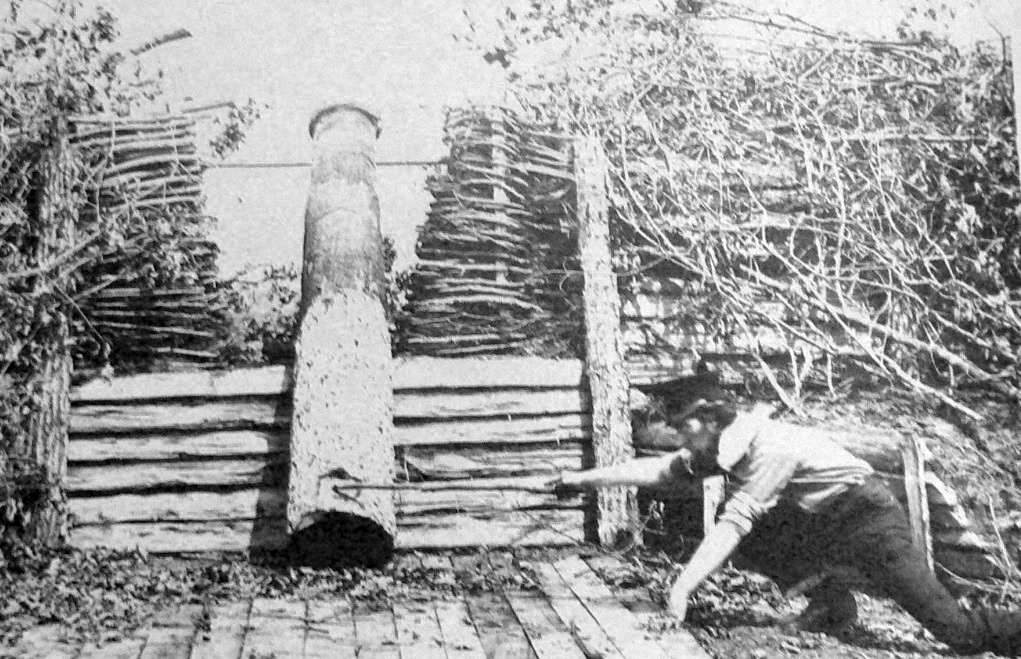

Taken after the capture of Confederate batteries along the upper Potomac, this U.S. Soldier ‘fires’ a Quaker gun. Carved from tree trunks, the ruse tricked Union intelligence balloons in to overestimating the size of the batteries.

Just to be sure, I felt around more exploring the surface of the gun and took a length from the trunnion to the extant breech, a distance of 37.5 inches. The shape and dimensions were too strongly cannon-esque. Armed with this knowledge, I had to do the last thing I wanted, abort the dive and surface.

The research agreement between IMH and MHT specified that any discovery of ordnance on the site would terminate diving. The presence of the cannon also pointed towards the vessel’s role in the Civil War and not just a canal boat sunk in the river. Under the Sunken Military Craft Act of 2004 (SMCA) this vessel is still government property. The SMCA act clearly stipulates that any and all vessels ever owned by the U.S. Navy, or caused to be sunk by the U.S. Navy are still legal property of the Navy.

Thus, without a permit, it is not legal to disturb or remove anything from the wreck. Working closely with MHT and NHHC, we immediately informed them of our findings and hauled down the dive flag.

Taken in April of 1865, these two canal boats are loaded with furniture from destroyed houses in Richmond, Virginia. The boats are typical of canal boats used on the James River & Kanawha Canal and elsewhere along inland waterways on the east coast. The Shipping Point wreck is very similar in construction and size to these boats. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Leave only Bubbles

Shipwrecks in this condition are rare. Wrecks in this condition intact with their wartime cargo are even rarer. The discovery of such a high degree of preservation is tempered by the knowledge that since 2011, the site has suffered some major deterioration. While diving the wreck, I was able to observe timbers pulled out of place, likely snagged by fishermen’s anchors.

Similarly, divers found monofilament line of all sizes tangled over the wreck, a hazard to divers as well as the wreck. Inadvertently, the wreck is being pulled apart. As recreational boating traffic increases, so too does the chances that it will be discovered by someone who is unaware of laws protecting submerged archaeological sites.

Through efforts of each partner organization involved with this project, we seek to increase public awareness of the fragility of archaeological sites. A site looted is a site that no one can enjoy, a site lost to science and humanity.

Similarly, we want to share the stories of our submerged history. People can best understand, appreciate, and steward something they are connected to. Understanding history, using the tools of archaeology, is an exciting way to explore our past and make that connection. IMH and LAMP encourage people to get involved with maritime history, to explore the silent world, to connect, and remember to take only pictures and leave only bubbles.

Special thanks to IMH volunteers Earl Hemminger, Todd Hutchings, Bill Isbell, Dan Lynberg, Vinnny Mallardi, Lee Nelson, and Charlie Reid for their support. Additionally David Howe (IMH), Dr. Susan Langley (MHT), Dr. George Schwarz (NHHC), and Dr. Gordon Watts (TAR Inc.) contributed significantly to the organization and success of this project. Last, but not least, thanks goes to the staff of the St. Augustine Lighthouse & Maritime Museum for helping make all of our research projects a success.

Brendan Burke joined the St. Augustine Lighthouse & Maritime Museum in 2007 as an archaeologist for the Lighthouse Archaeological Maritime Program. He holds a graduate degree in Anthropology from the College of William & Mary.