This fourth installment in our ongoing series on the history of the St. Augustine Lighthouse focuses on the tenure of Joseph Rantia and the arrival of our longest serving head keeper Peter Rasmusson.

Click the links below to read previous posts in the series:

- Lighthouse History Pre-1874

- Lighthouse History 1874-1894 (Part I)

- Lighthouse History 1874-1894 (Part II)

1894-1914

Promoted from 1st Assistant upon William Harn’s death, Joseph Rantia (often spelled Ranty) served as head keeper of the St. Augustine Lighthouse from 1889 to 1901, a span almost as long as Harn’s 14-year term. Rantia was a descendant of the Menorcans of New Smyrna like the Andreus and many other St. Augustine lighthouse keepers before him.

Rantia Family Tragedy

At 9:00 p.m. on September 23, 1894, tragedy struck the Rantia family when Joseph’s wife Mary died. Joseph carried on working at the lighthouse and the Keepers’ Log records the continuous labor required to keep the lighthouse maintained and operational.

The log is filled with reports of the keepers painting some part of the light station. The lighting and clockwork mechanisms often required repair and maintenance. This was, of course, in addition to the nightly duties required to keep the light operational.

Keeper Swap

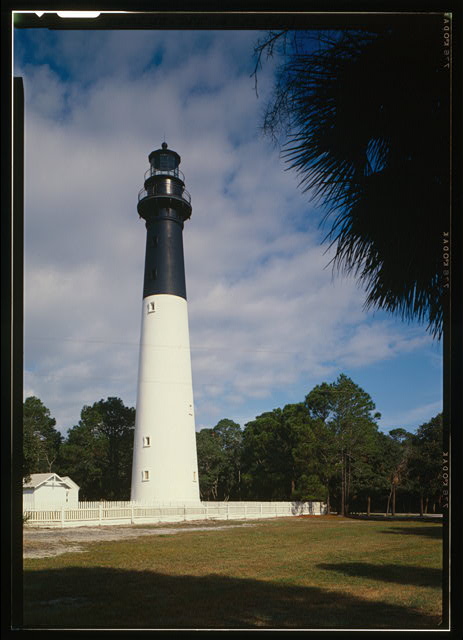

In 1901, after 12 years at the St. Augustine Lighthouse, Joseph Rantia transferred to Hunting Island Lighthouse outside Beaufort, SC.

Rantia took the place of Peter Rasmusson who in turn transferred here and began the longest tenure as head keeper at the St. Augustine Lighthouse, staying 23 years in the position. When he arrived, Rasmusson was making $720 a year.

Lightning and Lighthouses

Unaffected by the changes in personnel, natural forces continued to impact the light station, this time in the form of lightning strikes.

Between 1898 and 1908, the keepers recorded four lightning strikes, three of which struck the tower while the fourth hit the new Navy Wireless Station built in 1905. Though physical damage from the strikes was limited, they often affected the electrical wiring in the tower.

The 1906 lightning strike on the Wireless Station “did much damage,” according to the Keepers’ Log, although the brief description does not expound on the type and extent of that damage.

On August 11, 1908, a lightning strike hit the tower and ran along the call bell wires used to communicate between the tower and the house, which in turn “tore out part of [the] front door frame and casing in [the] Assistant Keepers quarters,” though they recorded no damage to the tower during the hair-raising incident.

The lighthouse is still a frequent target of lightning strikes, and during stormy weather we ensure the safety of our visitors and staff by restricting access to the tower.

Improvements bring relief for keepers & their families

Peter Rasmusson served during a time of great change for the light station, though most of those changes focused on making his daily life more enjoyable. On June 20, 1907, he recorded that they had “commenced installing bathtubs, closets, and lavatories” in the keepers’ house and that by August 3, “Mr. J.C. Libby finished plumbing on [the] dwelling.” These no doubt greatly improved the keepers’ quality of life, no longer having to rely on cisterns and privies.

Improvements to the station continued in 1909 with the installation of a new incandescent oil vapor lamp, which increased the intensity of the light while reducing the need for constant cleaning of the lenses and lamps. A 1908 report on Great Lakes lights states an expected brightness increase of between sevenfold and tenfold due to the installation of the new technology.

According to a 1915 report filed once the adoption of oil vapor lamps became more widespread, the…

“…vaporized kerosene under an incandescent mantle [gave] a much more powerful light with little or no increase in oil consumption.”

This was the last major improvement in lighting before the introduction of electricity. The cleaner burning lamp decreased the amount of effort the keepers put into maintaining the lamp during the night and did not replace that work with an increase in oil consumption.

Increase in light station guests

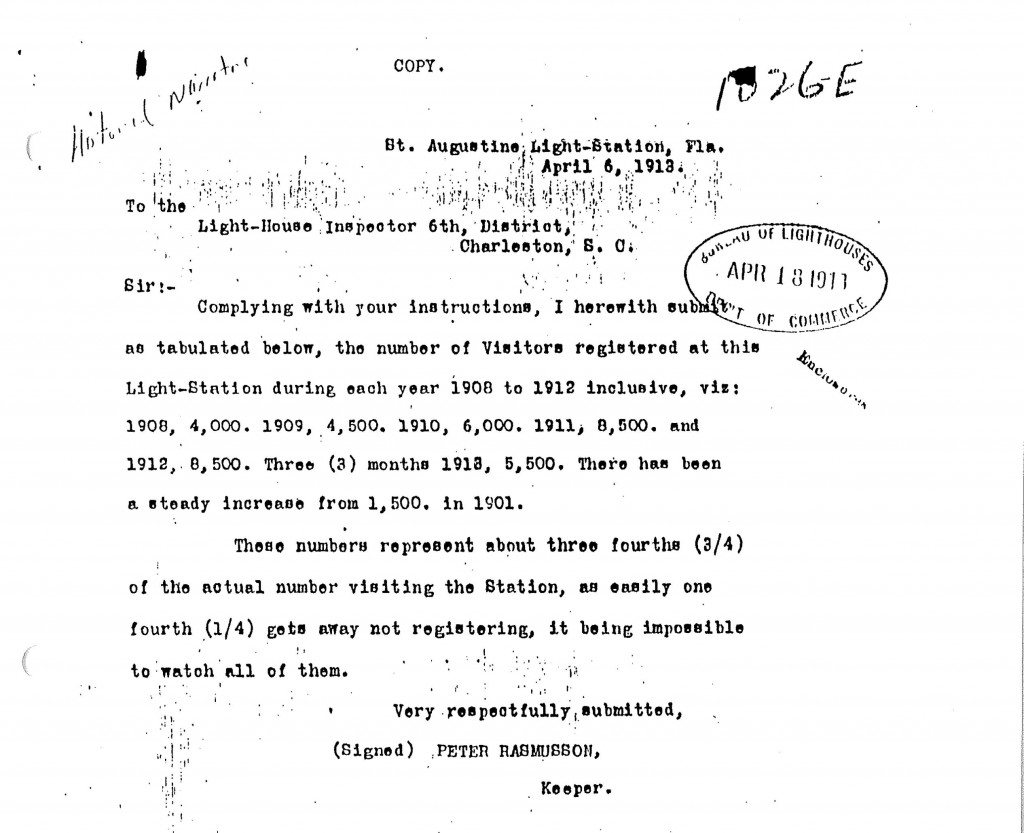

During the late 19th century and into the 20th century, St. Augustine grew as a tourist destination and the lighthouse became increasingly popular among the city’s visitors. In a 1913 report, Rasmusson reported a total visitation of 8,500 in 1912, with 5,500 visitors already in the first three months of 1913.

He noted, “there has been a steady increase from 1,500 in 1901” when he took over a head keeper. He even concedes that these numbers are likely inaccurate “as easily one fourth (1/4) gets away with not registering, it being impossible to watch all of them.”

Despite some moments of excitement, much work, and many visitors, some days the keepers log simply reports “nothing of interest to record,” a testament to the often monotonous duty of a lighthouse keeper.

Visit the St. Augustine Lighthouse & Museum and take a Behind the Scenes tour to learn more about the light station and the families that lived and worked here!

Paul Zielinski is Director of Interpretation for the St. Augustine Lighthouse & Museum. He received his master’s degree in Public History from the University of West Florida and joined the lighthouse family in 2011.