LAMP Director Chuck Meide (center) poses with 2012 Field School students and 2013 Field School Supervisors Olivia McDonald (left) and Loren Clark (right) outside the Lamp Lighters Pub in Leicester, England, during the 46th annual Conference on Historical and Underwater Archaeology.

2013 started with a bang for me as LAMP’s Director, and for our research on the Storm Wreck, the Revolutionary War-era shipwreck that we have been excavating offshore St. Augustine. On January 8th I flew from Jacksonville to Heathrow Airport in London, from whence I would travel (along with my colleagues Dr. John de Bry from the Center for Historical Archaeology and Michael Krivor from Southeastern Archaeological Research, who arrived on a later flight) by train to the city of Leicester, in the East Midlands of England.

In Leicester this year were the meetings of the Society for Historical Archaeology, or more formally the 46th annual Conference on Historical and Underwater Archaeology. After five days at the conference, networking with archaeological colleagues from across the globe (including some of our former field school students) and hearing everyone’s latest research, I was to spend an additional four days in London, at a bed and breakfast in Kew, where I was eagerly awaiting the chance to peruse documents in the National Archives (formerly the Public Records Office), in an attempt to learn as much as we possibly could about the Storm Wreck which we have been excavating offshore St. Augustine.

The primary sponsor of the SHA conference was the University of Leicester, which provided the lecture halls for the many presentations from archaeologists from around the world.

Each day I walked from the conference hotel to the university campus. Leicester is really a lovely city, with cathedrals and medieval architecture, and the pleasant New Walk, which ironically is built on an old Roman road. Pictured above is Leicester Cathedral.

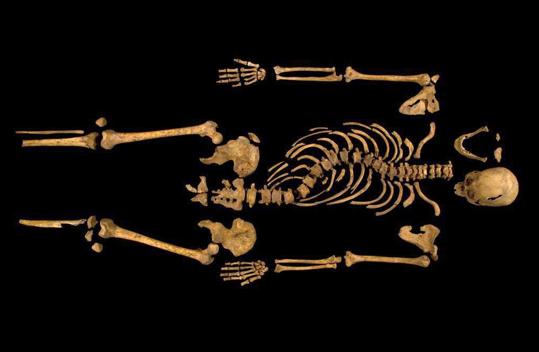

The University of Leicester has made international news lately with the announcement of the discovery of a skeleton which has been definitively identified, through osteological and DNA evidence, as the remains of King Richard III. Richard III was the last Plantagenet king of England, and met his death in Leicester at the Battle of Bosworth Field. In this last battle of the War of the Roses, Richard fell to the army of the future Tudor king, Henry VII, the grandfather of Queen Elizabeth and father to King Henry VIII.

The skeleton bore evidence of a severely crooked spine due to scoliosis. Richard III was known for this condition, and is regularly portrayed in Shakespearean plays with a hunchback. The skull displayed clear evidence of traumatic injury, including a wound which sliced off the base of the skull and exposed the brain. The King was known to have been killed by a halberd blow to the head. There were also many wounds that were clearly caused by weapons striking from behind, on the back and buttocks. These are believed to be “humiliation wounds” enacted on the body after death, and are consistent with the contemporary descriptions of Richard’s naked body being tied across a horse with his legs and arms dangling down. After the conference, in February, the University announced that DNA samples from the skeleton matched those from the son of a 16th generation grand-neice of Richard III living in Canada identified through a genealogical study. The evidence is indisputable, and it was an exciting time to visit Leicester.

After the conference I traveled back to London, and arrived at the lovely suburb known as Kew. It is famous for its Gardens, and also for housing Britain’s National Archives. I have twice before conducted research in the Archives, back when they were known as the Public Record Office in 2000 and again in 2005.

I stayed in a wonderful little Bed and Breakfast known as Maze Lodge. The owners cater to researchers coming to work at the Archives, and it was only a two minute walk from the B&B to the National Archives. That was a good thing, since it was so cold there were a few days that I had to walk through the snow! We’re not used to that in Florida.

The entrance to the National Archives. Researchers from around the world come here each day, and in fact during the days I worked here I ran into three colleagues, two Canadian friends and one American.

In fact it was so cold, I saw something unheard of in Florida . . . seagulls on ice!

Once entrenched in the Archives, I was hard at work each day. From start to close I spent the day searching through records looking for any trace of our shipwreck, including any information on the evacuation of Charleston at the end of the Revolutionary War, and of the 71st Regiment. We believe our shipwreck was in the final fleet to leave Charleston at the end of the War, and that at least one member of the 71st Regiment (Fraser’s Highlanders) were on board.

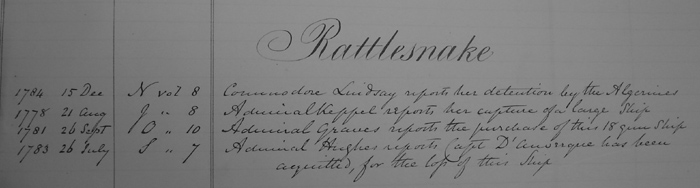

One loose end I wanted to follow was the ship Rattlesnake. We know that the galley Rattlesnake was one of the vessels lost in the wrecking event off St. Augustine that took place around 31 December 1782, and that it appears to have been the only naval ship lost in the incident. As the Royal Navy kept meticulous records, I thought there was a chance of finding the ship’s log or documents related to the captain’s courtmartial. Unfortunately, while I found a number of records related to naval ships named Rattlesnake, none of them appeared to be the Rattlesnake that was lost off St. Augustine in 1782.

One thing I did find records of was a sister ship to the Rattlesnake, the Viper. The old, leather-bound book pictured above is the muster roll and paybook for the galley Viper. This is an interesting document, as it provides details on the crew of this galley, which like Rattlesnake was used by the British to patrol the waters of Northeast Florida during the Revolution. It tells us the compliment of men, and in many cases where each was born, how much they were paid, or whether they died on duty or deserted the ship.

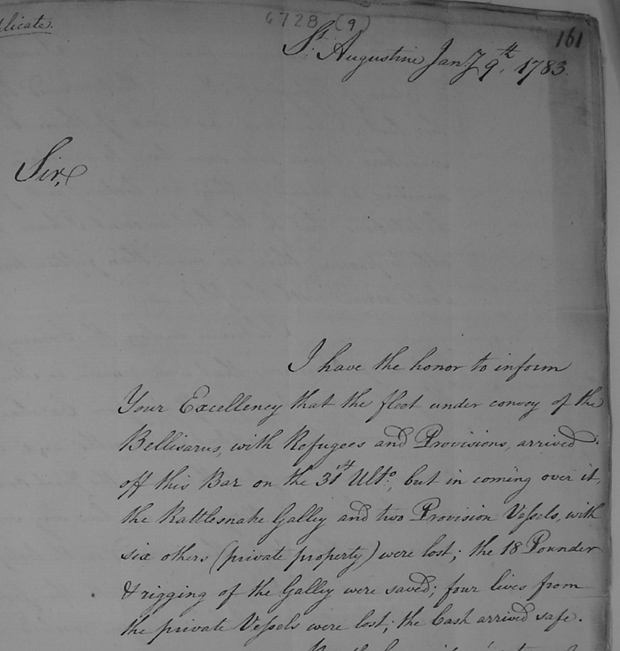

Pictured above is a key document that I was able to find. This was the letter dated 9 January 1783 from East Florida’s British Governor, Patrick Tonyn, to the British Commander in Chief Sir Guy Carleton in New York. In it Tonyn reports the loss of the Rattlesnake, along with two victualing ships and six private vessels. There are still some discrepancies in our understanding of the wrecking event, as Tonyn lists nine ships lost, while the Loyalist Elizabeth Johnston writing on 3 January 1783 mentions that sixteen ships were lost on the sandbar, and another six or eight wrecked on the beach. The German surgeon Schoepf, who visited St. Augustine a year later, corroborated Johnston’s account as he mentioned sixteen ships lost on the bar.

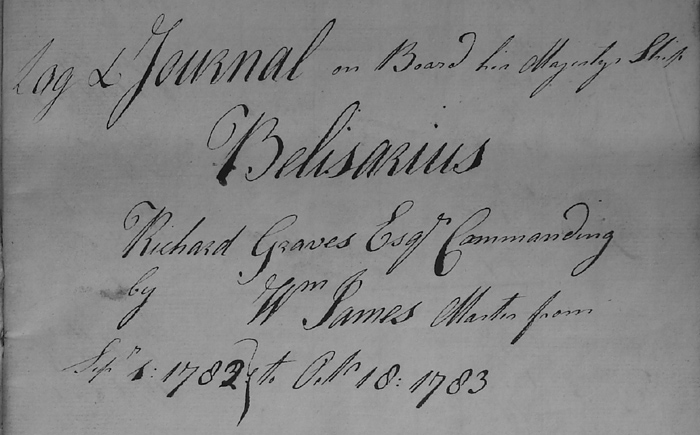

Above is the title from the ship’s log of HMS Belisarius, the naval vessel that Tonyn mentioned as escorting the fleet from Charleston bound for St. Augustine. I actually found two logs, that of the captain and that of the master, and they confirm that Belisarius was the vessel protecting the portion of the evacuation fleet bound for East Florida. While we are still going through these logs, we expect to find some key information related to our shipwreck.

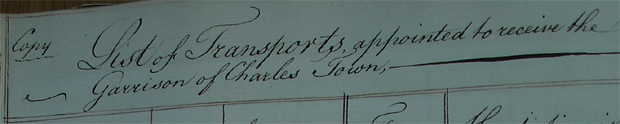

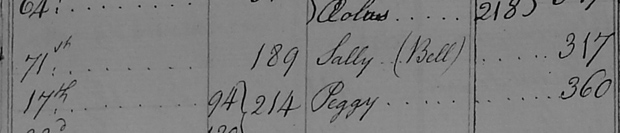

Another key document discovered was a list of the vessels used by the Army to evacuate Charleston. This one, dated about a month before the fleet departed Charleston, details which squadrons were going to which destination, including Jamaica, St. Lucie, England, and Halifax. While we know some vessels ended up going to East Florida and St. Augustine, they are not listed separately on this list, unfortunately.

But, on the other hand, it does provide a vital new piece of information. The surviving troops of the 71st Regiment, which numbered only 189 men, were to be loaded onto the ship Sally and bound for Jamaica. At least one of the members of the 71st never got there but was instead shipwrecked at St. Augustine, as evidenced by the 71st regimental button recovered from the wreckage. We don’t know if our Storm Wreck is that of the Sally, who perhaps for some emergency tried to enter St. Augustine, or if some of the soldiers of the 71st were on other ships, perhaps to provide armed protection from predatory privateers. We know there were soldiers from a provincial unit also on board the Storm Wreck, evidenced from the Royal Provincial button also recovered from the wreckage. According to this document, the provincial troops were on other vessels, so we don’t quite yet have our smoking gun, and aren’t ready to say definitively if we have the shipwrecked Sally or another vessel, but we are one step closer to the truth.

All in all, I recorded over 1000 pages from more than 100 documents related to the evacuations of Savannah, Charleston, and New York, including several other lists of transport ship names, along with letters from the colonial office and commander in chief’s office and records related to the 71st Regiment. Right now we have volunteers who are perusing the documents, which have all been sorted and are safely stored on our computer server. Our volunteers have begun the slow process of transcription of what is often pretty awful handwriting. Stay tuned to the Keeper’s Blog to learn the latest discoveries from the documents!