Just after dawn the morning of 6 July the crew of Cruise 1 loads the Roper for a four day expedition to search for shipwrecks off Jacksonville.

There’s no rest for the weary at LAMP! Just three days after wrapping up our annual field school, which focused on the excavation of the late 18th century Storm Wreck (including the raising of two cannons!), we’ve already switched gears from a local, day-trip excavation to a remote, liveaboard survey operation. During the month of July LAMP’s research vessel Roper (on loan from the Institute of Maritime History) will remain out at sea (other than brief visits to shore to re-fuel and switch out crews) conducting almost continuous survey to search for shipwrecks. This entails a much smaller crew (we’ve gone from often more than 20 on the boat to just 4) and it involves overnight stays on research cruises lasting four days at a time. We have adopted this new methodology to most efficiently survey in areas more remote from our traditional stomping ground of St. Augustine. For the first three cruises we will be conducting sonar and magnetometer survey off the St. Johns River and Fort George Island Inlets (off Mayport and Jacksonville, Florida) some 40 miles north of St. Augustine. Then for the final three cruises we will be targeting the area surrounding the Matanzas Inlet, 16 miles south of St. Augustine, and the traditional “back door” to the nation’s oldest port.

The purpose of this expedition is discovery, and we think it is likely that we will discover one or more historic shipwrecks in these two areas.

We are underway by 0710, out the St. Augustine Inlet with nothing ahead of us but the vast blue sea . . .

Lizz Zieschang, an undergraduate student at State University of New York at Potsdam, takes the helm on the cruise up the coast.

Because we are staying overnight on the boat for four nights at a time, we have sharply reduced our crew size. The team for Cruise 1 (July 6-July 9) consists of LAMP Director Chuck Meide, LAMP Archaeologist and Logistical Coordinator Brendan Burke, LAMP Intern Archaeologist and recent Flinders University Masters graduate Matthew Hanks, and SUNY Potsdam undergraduate student Lizz Zieschang.

Matt Hanks relaxes on deck during the cruise from St. Augustine to Mayport.

As we approach Jacksonville, the marine traffic increases noticeably. Mayport, the fishing port at the mouth of the St. Johns River, is a well-known center for shrimping, and there are still around a dozen or more shrimp trawlers operating out of Mayport today. Also seen in this picture is an example of the commercial traffic operating out of the port of Jacksonville.

This large container ship is one of many that travels to and from the port of Jacksonville on a regular basis. While St. Augustine is the birthplace of commercial shipping in the U.S., Jacksonville surpassed St. Augustine in the 19th century as a commercial shipping center, and it remains a major commercial port today.

Jacksonville, like colonial St. Augustine, is also a military port. Naval Station Mayport is within view of our survey areas. Here is a cruiser making its way out the inlet, which is bounded on either side by rock jetties.

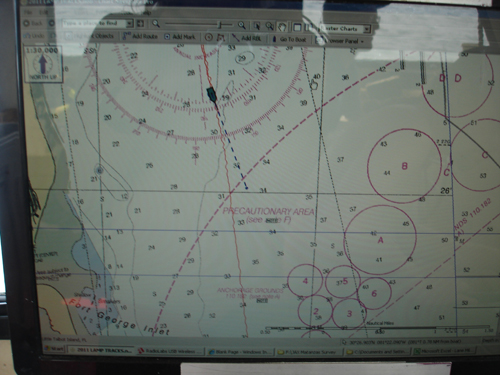

Once we have arrived at the mouth of the St. Johns River, we prepare for our first survey work. We are going to tow our remote sensing equipment in a back and forth pattern over a survey block designated Fort George Survey Block. This stretches from the jetties at the mouth of the St. Johns four miles northward, across the mouth of the Fort George Island Inlet and terminating at the northern end of Little Talbot Island. We believe this is a high probability area to find historic shipwrecks. Jacksonville was a heavily trafficked port from the 19th century onwards, and it is likely there are wrecks on the periphery of its inlet (though the inlet itself has been heavily dredged, probably destroying many wrecks). Fort George Island Inlet would have served plantations,.such as the early 19th century Kingsley Plantation, and should also feature shipwrecks. In the late 18th century, during the American Revolution, there was a sizable settlement of British loyalist refugees at the mouth of the St. Johns River. The Mayport area was settled as early as 1562 by the French, and thus there is some potential for earlier wrecks as well. The entire crew is excited at the prospects of this survey.

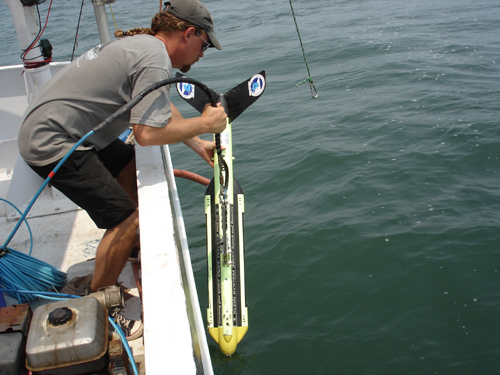

Brendan deploys the side scan sonar “fish” by carefully lowering it into the water. It will be towed directly from the smaller lifting arm on the Roper’s stern. LAMP owns a Klein 3900 side scan sonar system.

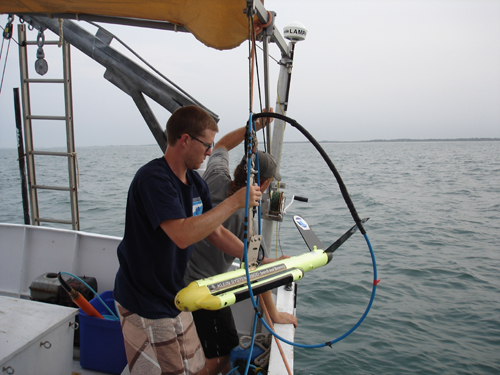

Next in the water is the magnetometer. Like the sonar, its sensor head is a torpedo-like device known as a “fish,” but it must be towed much further behind the Roper since our boat is made of steel and the mag acts as a metal detector. Our magnetometer is small and lightweight, and is manufactured by Marine Magnetics in Canada.

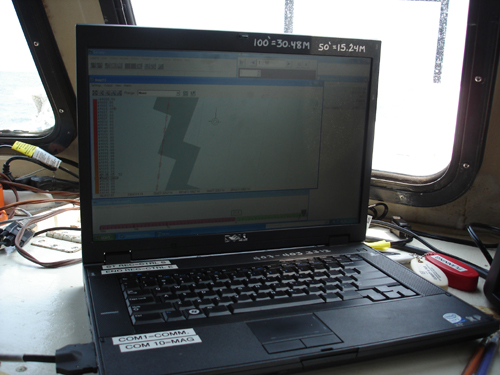

Inside the Roper‘s cabin, the brains of our remote sensing system are operating (and I don’t mean Brendan and Matt! Just kidding . . .). Both the magnetometer and the side scan sonar feed data to computers which are constantly monitored by LAMP technicians.

The sonar laptop displays a visual representation of the seafloor, generated by the acoustic signals that the sonar fish sends out and interprets as they bounce back from the seafloor. We can see sand ripples, scars from shrimp trawls, and other bottom features, including any ship wreckage that might be protruding from the seafloor.

The magnetometer fish feeds its signal to a second laptop, which also features the navigational software allowing the boat operator to follow pre-determined survey lanes. This laptop also provides constant readings of the earth’s magnetic field in gammas, as recorded by the magnetometer fish. This lets LAMP technicians know if the boat has driven over an area containing ferrous material (iron or steel). Even if a historic wreck is buried, its magnetic signature can be detected with this sensitive device.

We survey for around six hours, from around 2 pm to 8 pm, and finish seven of our survey lanes for a total distance of more than 30 linear miles. That is a good day’s work, considering our four hour commute from St. Augustine, so we expect to get even more work done tomorrow. That is a good thing, since in this survey block alone there are 150 planned survey lanes! But it is a great start to the project, and at the end of the day the equipment is brought back onto the boat safe and sound.

With the final glow of the sunset fading behind the shore, the crew relaxes as the Roper gently sways on her anchor line. Survey is harder work than it looks, especially for the boat operator who really has to put some muscle into handling the helm and keeping the boat on course to its tracklines. As we all take shifts performing each required job–boat captain, equipment technician and screen monitor, on-deck cable watcher–we are pretty tired after our 15 hour work day. After a meal of cold but delicious jambalaya (featuring St. Augustine shrimp spiced by St. Augustine datil peppers and Minorcan sausage) its time to relax and get a little fishing in, while also taking the time to finish writing and uploading this blog. And perhaps ponder what sunken vessels lie beneath, awaiting discovery.