Students and teachers from the 2010 Field School on board the research vessel Roper.

Things have been so busy during this year’s field season that I’ve had no time whatsoever to blog about our activities! Last week we finished a great field school, which brought 9 students eager to learn, and 4 returning students from last year who served as supervisors, for what turned out to be one of our best field school experiences to date. I’ve picked out a bunch of great photos so everyone can see what our students were up to during the four-week long period from May 31 to June 25.

All field school participants undergo an intense three-day training period, where they learn the basics of archaeology and scientific diving. Because scientific diving involves significant diver task-loading and is much more challenging than recreational diving, we follow strict training and safety standards, which mirror those developed by the American Academy of Underwater Sciences. For the students, this involves a written scuba exam and a swim test and scuba checkout in the pool. Here the students are participating in a ten minute water-treading exercise. For the last two minutes, no hands are allowed!

Part of our pool training is a specialized blackout-mask obstacle course. Student divers must navigate a very complex obstacle course with black duct tape covering their masks. There are countless entanglement hazards set in place throughout the pool bottom, in addition to staff divers mixing things up by purposely snagging the divers’ gear with bungee cords and the like.

Completing this obstacle course is a great way to prepare our students for our local dive conditions, which regularly feature poor to non-existent visibility, along with numerous real entanglement hazards. Here student Pat McGovern of Roger Williams University in New York blindly follows the guideline under simulated wreckage, while a supervising diver secretly attaches a bungee cord to his gear. Once Pat realized he was stuck, he had to locate the snag and remove it.

During the first week and a half of Field School, Dr. David Switzer, Professor Emeritus at Plymouth State University, presents a series of lectures focusing on a wide variety of shipwreck and other maritime archaeological sites, and the various techniques that have been used in different environments. Dr. Switzer is a pioneer in the field of maritime archaeology and we are so proud to have him associated with our field school. In this picture, LAMP Director Chuck Meide is to the left of Dr. Switzer, helping prepare for his next lecture.

The students are also given a behind-the-scenes tour of the St. Augustine Lighthouse & Museum’s Collections Facility, located off-site but nearby. Here they inspect a 1:12 model of the Steamship wreck, which will be their first dive in St. Augustine waters.

As safety is our number one priority when conducting scientific diving, all of our students also undergo hours of training in oxygen administration, advanced oxygen administration, first aid for hazardous marine life, marine AED administration, and diver neurological assessment. This training was taught by two industry professionals who participated in the Field School as students to learn more about underwater archaeology, Bill Chalfant and Jim Wright. Bill is an experienced PADI dive instructor and the Director of the School of Diving at the Florida Keys Community College. Jim is a NAUI instructor and diving medic, and an EMT and firefighter in Sarasota. Their combined knowledge and experience in diving first aid and accident management is very impressive, and they ran a great training program for the rest of the students. Here Bill awards student Carmeline Panico (University of Delaware) with her DAN training certificate.

The students live in dorm-style accommodations at the LAMP Field House, located a few miles west of St. Augustine. Here on the back porch the students spend their evening hours making PVC grids which will be used for mapping and excavation on the shipwreck site offshore. From left to right are Jim Wright, Alex Vidal (University of South Florida), Pat McGovern, and Katie Kelly (University of Indianapolis).

The students learn that there are many other types of maritime archaeological sites than submerged shipwrecks. Here they inspect at low tide the coquina foundations of the 18th century St. Augustine Lighthouse, which collapsed into the sea in 1877, only three years after the present-day tower was completed.

The students also participate in recording the remains of a boat landing site on the foreshore near the Lincolnville neighborhood of St. Augustine. This traditional African-American neighborhood was settled by freed slaves shortly after Emancipation. The Lincolnville Landing site consists of a series of heavy timbers laid out parallel to shore which are exposed at low tides. They created a “hard” or area in which one could easily walk or launch boats in what would otherwise be a muddy quagmire. Pictured here are, from left to right, supervisor Wendy Drennon and students Jim Wright, Alex Vidal, Pat McGovern, and Carmy Panuco. They are recording a profile view of the landing structure.

On a subsequent day, a second group of students works at Lincolnville. Here are students Devin O’Meara of Grand Valley State University of Michigan and Katie Kelly of the University of Indianapolis.

But the students are eager to get offshore, to use the diving skills they have honed during the first week of training and to experience working on sunken shipwreck sites associated with America’s oldest port. Conducting diving and archaeological operations offshore is an equipment-intensive endeavor, as can be seen by our fully loaded truck waiting at the Lighthouse Boat Ramp Dock, where we depart every morning around 0700. We meet at the Lighthouse every morning at 0600, as it takes about an hour every day to assemble and load all of the equipment.

Here the students load 40′ or so of dredge hose, which will be used to excavate a newly discovered shipwreck site offshore.

Our primary research vessel is the Roper, a 36′ steel dive boat and former shrimper, seen here making her way out the St. Augustine Inlet into the Atlantic Ocean. The Roper is very generously on loan to LAMP by the Institute of Maritime History, one of our partners who has helped make this such a successful Field School. Her home waters are the Chesapeake region.

Joining the Roper is the RV Desmond Valdes, LAMP’s primary research vessel, which was donated to our program last year by the Valdes family. The Desi is a 23′ Grady White and a fine vessel for survey or diving operations. On our first day out, she is skippered by LAMP’s Director of Archaeology Dr. Sam Turner, with Field School Supervisor Megan Staley serving as first mate. Megan, who will graduate from Kansas State University later this summer, was a student in last year’s Field School who has returned to work as a Supervisor this year. She will also be joining LAMP as an intern after her graduation.

Field School students Carmy and Pat relax on route to the site . . .

. . . while Field School Supervisor Wendy Drennon takes a turn at the wheel of the Roper. Wendy is a recent graduate of Florida State University, and she has been accepted for the master’s program in maritime archaeology at Flinders University in South Australia. Wendy was a student in LAMP’s 2009 Field School, and returned this year to work as a supervisor.

Our primary shipwreck site this year is a newly discovered wreck known as the “Storm Wreck.” It is located off St. Augustine Beach, about a mile or so offshore in around 25-30 feet of water. It was found after a LAMP magnetometer and sonar survey conducted in the summer of 2009. LAMP at that time made one dive on the site, which is completely buried in the sand, and located an iron cauldron, a wooden plank, several iron concretions, and a few ballast stones. This mix of material culture strongly suggests a shipwreck site, and possibly an early one dating to the colonial period. As it was discovered during the last week of last year’s diving season, nothing beyond this initial probing and observation was accomplished. We are planning on re-locating the wreck site and excavating several square meters of it in order to better understand its nature, extent, condition, age, nationality, and function. The first step is to find the wreck again. We documented its position with a sophisticated GPS which records geographical locations with sub-meter accuracy. Here the GPS antennae, with a long cable payed out from the boat, is passed to student Devin O’Meara in order to pinpoint the wreck location as accurately as possible.

Devin, following directions from staff on the Roper, moves a buoy to the exact location provided by the GPS. Afterwards divers conduct a circle search underwater and relocate the submerged marker left in place the year before.

The next step is to set out permanent mooring anchors. We place two of these anchors, and record their locations with a handheld GPS, well beyond the site boundaries. Once in place, we can moor our boat over the site using three anchors, which allows us to stay in place over the wreck or adjust our boat placement as needed. This is important as there will be multiple hoses running from the boat to the wreck, and if we were to drift with the tide we would have to re-deploy the vessel constantly. Here Field School Supervisor Chris Borlas and student Katie Kelly swim out the anchor using a float before dropping it in place. Chris, who graduated from the University of Florida, was a student in last year’s Field School who returned to work as a Supervisor this year.

The Storm Wreck is a very exciting find, in part because it is completely buried by sand. This made it more difficult to locate, and will make it more challenging to excavate, but it also suggests that it has remained hidden to local divers and potential looters, and so most likely represents a pristine time capsule. Before we disturb the site any further, we have decided to conduct a hand-held magnetometer survey over a ten meter square area centered on the known location of the cauldron. This is done by establishing a non-magnetic grid over the area, and sending divers in to record magnetic readings every meter within that gridded area. Here Field School Supervisor Kaia Brown passes the handheld magnetometer to LAMP Archaeologist/Logistics Coordinator Brendan Burke and student Bill Chalfant. Kaia is a returning student from last year’s Field School who recently graduated from the University of Minnesota, and will be attending graduate school at Cranfield University in England to study forensic archaeology.

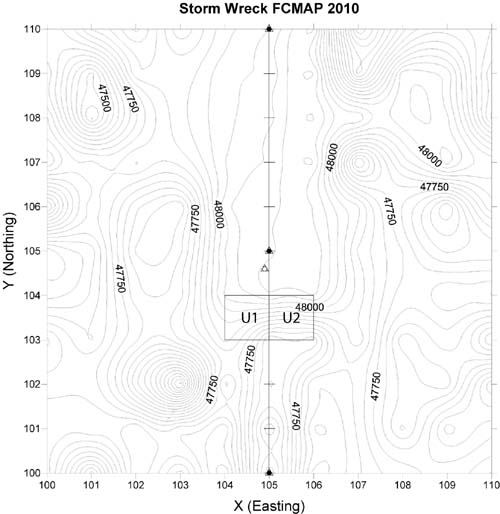

A total of 121 readings are recorded for this survey, and after the readings are typed into a spreadsheet LAMP’s trusty volunteer Tim Jackson processes the data using a contouring software. The resulting magnetic contour of the site is shown below, superimposed with the first two planned excavation units. This map suggest there are numerous other “hot spots” in the area, a pattern consistent with a wrecked ship buried beneath the sand.

Our next task is to prepare for excavation by laying out the two excavation units, to be labelled Units 1 and 2, which are shown on the map above. These will be defined by a one meter by two meter PVC grid, attached to the seafloor by two ten meter long segments of polypro line. Here Dr. Sam Turner, LAMP’s Director of Archaeology, prepares to dive to deploy the grid on the seafloor. We hope to place the grid directly over the location of the cauldron which was briefly exposed by LAMP divers last year.

We have had a few VIP visitors to the site during this Field School. Here Lighthouse Board member Captain Ray Hamel chats with LAMP archaeologist Brendan Burke. Ray is a very experienced boat captain who occasionally volunteers his time and expertise to assist in LAMP’s operations.

At this stage we are ready to begin excavation on the wreck. Not surprisingly, we are all very excited at this prospect, as we are all dying to know how old this newly discovered wreck its, and what artifacts lie preserved beneath the sand. Enhancing our excitement is the uncharacteristically good visibility on site. During our several days of set-up, divers have been able to see as much as one to two feet underwater, which is pretty darn good for St. Augustine waters.

But, as these things often go, we face unexpected hardships which cause a rapid change in plans. Roper has suffered an uncharacteristic engine problem, and it will take a week for a diesel mechanic able to handle the problem to travel to St. Augustine, remove the faulty part, repair it in the shop, and return to re-install. In the meanwhile, we cannot get all of our students offshore in our smaller boats, so we switch to an alternate inshore site in St. Augustine’s harbor. As it turns out, this is also an exciting site, a recently discovered possible shipwreck site, and for the next week we benefit from working on a different site in a very different environment, with its own challenges and rewards. You can read all about our work on the Bayfront Ballast site, and our return to the Storm Wreck, in the second installment of this blog entry, coming soon . . .

Click here to read Part II of the 2010 Field School blog post

Coming soon! Part III