Sliding along quietly through the marsh we inspired nothing more than nonchalant looks from bankside egrets. Looking like a routine fishing boat, the marsh waders and herons went about their day and life seemingly went on as normal through the tidal flats. However, the scene underwater was much busier. A constant and rapid pinging sound was emanating from the boat, one gathering historical data and ‘seeing’ Robinson Creek’s bottom for the first time.

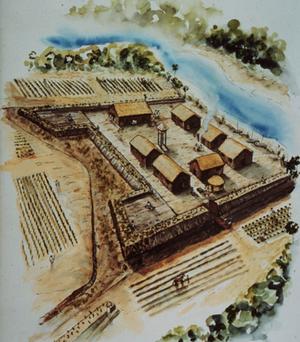

An artists depiction of Fort Mose. (Image courtesty of the U.S. National Park Service)

As part of the First Coast Maritime Archaeology Project, marine survey plays a vital role. Recently, archaeologists from LAMP have been working with two creeks to capture images of the creek bottoms in the search for historic sites, debris, artifacts, and other unknown anomalies. St. Augustine’s waterways have absorbed much of its material history as trash was discarded, items were lost, and even sometimes intentionally hidden in out of the way places. For centuries, waterways were open receptacles for refuse and can contain an astounding collection of well-preserved material culture. The two creeks we have started with are Pancho Creek and Robinson Creek.

Aerial shot of Robinson Creek with the Fort Mose location. Occupants of the fort would have used the creek for transportation, harvesting oysters and fish, and as a defensive barrier.

There has been a focus for each creek, aside from the ongoing need to know as much as we can about the First Coast’s waterways. For Pancho Creek, there are the remains of a historic railroad grade through the marsh and crossing the creek as well as the Tolomato (North) River. Robin Moore, Historic Resources Specialist for St. John’s County, had asked us to look into this railroad grade and so while there, we surveyed all of the navigable creek. However, the focus here is Robinson Creek. The creek begins as a series of tributaries emanating in north St. Augustine neighborhoods. They quickly form a headwater at the edge of the tidal zone where marsh meets dry ground and then begins to flow in a northeasterly direction. The creek is not noteworthy for its excessive length, breadth, or depth. But it flows by the site of Fort Mose, one of the earliest free African American communities in North America.

To understand the levity of this community we need some quick context. Beginning in earnest during the early 18th century British dominion over the Carolinas quickly established a thriving industry in indigo, rice, and much later, cotton. Plantations often measured in the tens-of-thousands of acres and were their own communities. The intensive labor to plant crops, harvest them, dig irrigation and drainage ditches, as well as support the ancillary needs of the community was exclusively supplied through captive labor. Slaves brought from the Carribean, the Bight of Biafra (Africa’s slave coast), and other British colonies formed an expansive labor force, eventually turning the southeast into the world’s leader in rice and cotton production. Given the nature of enslavement and its horrible bedfellows such as malnutrition and torn families, escape was common. In the words of Kenneth Stampp (1989), slavery’s grandfatherly chronicler, “slaves longed for liberty and resisted bondage as much as any people could have done in their circumstances”

For an enslaved individual, especially during the early decades of chattel slavery, escape was often the only means of freeing ones self from the condition of bondage. Scholars who have studied enslavement often refer to escape as ‘maroonage’ and have well documented its elaborate and pervasive existence within and without enslaving societies (Aptheker 1943, Price 1996, Sayers 2006) The process of running away, then, takes on manifold meaning, primarily based on situational context. Maroon communities existed as outposts in the hinterlands of colonial settlements, as far flung towns, and even as camouflaged enclaves inside urban centers. The earliest documentation we have of African American maroonage in St. Augustine dates to 1687 when a group runaway slaves from northern English colonies seeks refuge in town. The Spanish Governor, Juan Marquez Cabrera, refused to hand over the escapees after English attempts at extradition. They ended up being put to work on the Castillo de San Marcos for wages after agreeing to convert to Catholicism. By 1738 the number of freedmen in Spanish Florida had grown to such a number that laws were in place to grant them amnesty and citizenship after conversion to the Catholic faith and having served four years of indenture to the Spanish crown. Gracia Real de Santa Teresa de Mose, soon to be know as Fort Mose, was founded as an isolated outpost to house the burgeoning community of maroons. It took the form of a four-sided fort and was to serve as an outer defensive mechanism for St. Augustine. As Spain’s northernmost outpost on the Atlantic coast, the town figuratively rubbed shoulders with British interests to the north. Colonial tensions constantly kept the two colonies at odds and in need of military protection. For Spanish purposes the influx of maroons was a windfall. They provided cheap labor, even when paid wages, and could be used to help fend off British assault. Not long after the fort’s formal inception would it prove to be vital in defending the gate to Philip V’s empire.

An 18th century depiction of freedmen in militia uniform.

Saving St. Augustine from attack, while meritorious and noteworthy, isn’t Fort Mose’s real claim to fame. While historians and archaeologists have documented the presence of maroon settlements and colonies throughout the New World this particular settlement was one of the first in North America to have an established and formal presence tied to a colonial power. Simply put, Fort Mose was a legitimized settlement of self-emancipated slaves, the first of such in what would become the United States. No such entity existed in the adjacent colonies to La Florida and nothing similar would occur until well into the 19th century and an international war on slavery had begun in earnest. Maroon settlements north of Fort Mose were illicit communities of runaways scattered throughout sea islands, swamps, mountain ranges, and other less-inhabited landscapes. While little is known about the social structures of these particular settlements, many of which have likely faded into the oblivion of history, it is known that they were looked upon by colonial leaders as pariahs to an economic system heavily reliant on forced labor. Thus, maroon settlements existed under a constant threat of attack and return to enslavement. For the inhabitants of Fort Mose the price of religious conversion and indenture was minimal, considering the benefit of protection from a colonial power. Catholic conversion for freedmen may well have been paying lip service to a colony offering protection. Surely, the chance to pick up arms in the Spanish militia may have also offered incentives to exact revenge upon British oppressors. Whatever the motivation for the individual, Fort Mose thrived until its Dunkirk in 1740 when British General Oglethorpe attacked St. Augustine.

Artist’s rendition of the 1740 fight at Fort Mose.

Acting as the first line of resistance, Fort Mose sapped energy from the British attacking forces and slowed their advance on the city. When it finally fell, the militiamen and citizenry of the fort withdrew to downtown St. Augustine. Oglethorpe briefly took the town but was repulsed with much help from the black militia. Until 1752 the fort stood empty and freedmen lived freely in St. Augustine. But after a twelve year period the fort was reestablished and once more St. Augustine has a separate hinterland for its maroon community. In 1763, when the British were finally successful in throwing the Spanish out of East and West Florida as a result of the Treaty of Paris, Fort Mose’s inhabitants moved with the rest of St. Augustine’s population to Cuba. This would be the last of the freedmen’s communities in St. Augustine since slavery was once again encouraged and the city’s Negro community was owned, not free.

Leonard Parkinson, a well known maroon captain in Jamaica during the Second Maroon War of 1795, following the First Maroon War of 1728.

Taking a slight diversion and without going into great detail and discussion I do suggest a re-visiting of the interpretation of Fort Mose’s place within the Spanish colonial world. Division along the color line undoubtedly existed within Iberian America but how was this manifested in Fort Mose? I believe that popular interpretations of the fort allow celebratory tones to mask a deeper understanding of race and colonization. This does not necessitate overshadowing the proud history of what historical archaeologists Kathleen Deagan and Darcie MacMahon call “Colonial America’s Black Fortress of Freedom”, rather, ensures a more composite image of Fort Mose’s real role in Spanish St. Augustine. Why was the fort physically segregated from the city center where commerce and politics were most active? Doesn’t its role as a ‘sacrificial anode’ for St. Augustine, combined with its spatial separation, provide rich commentary on new forms of racial marginalization and exclusion? How ‘inclusive’ was Spanish colonial praxis? These questions, any many more, I believe, keep the importance of Fort Mose alive. The site isn’t simply a monument to extraordinary human endeavor but a place for us to reinvestigate our understandings of how the past has impacted today.

Trelawney Town, a maroon settlement of reknown in Jamaica during the 18th century.

However, I don’t want to spend too much time here and return to Robinson Creek. After seeing what the sonar could do in Pancho Creek, I wanted to get as much of Robinson as I could. Dr. Sam Turner and I headed out in the LAMP vessel Nickerin one cloudy and windy afternoon. Arriving at the mouth of the creek we rigged the boat for survey, deploying the sonar towfish off of the boat’s bow. Survey in shoal water, especially creeks like this takes vigilance to watch for hidden mud bars, oyster reefs, crab pots sitting just beneath the surface waiting to foul a prop, and all kinds of debris that make you stay on your toes when deploying expensive instrumentation. On the previous creek survey I was lucky enough to have three people on the boat and while I was adjusting the towfish position off the bow one person was piloting and the third was counter-balancing my weight up front by standing at the transom. This way I was able to achieve a good set of the towfish immediately below the bow of the boat. Unfortunately, on deployment in Robinson creek the towfish wasn’t adjusted far enough below the boat so that one of the fins was riding on the port side of the cutwater the whole time, ultimately affecting the quality of the data. This can be fairly routine for marine survey, having everything set up, running and then finding out later that one little parameter was fouling a good data return throughout the survey.

Osmond, a maroon living in the Great Dismal Swamp of Virginia and North Carolina. His existence was documented by a traveller to the swamp, Porte Crayon (nom de plume of David Hunter Strother) in 1856.

Fortunately, the sonar data we retrieved was good enough for post-processing analysis (for a description of sonar use and post-processing see some of my earlier Sidescan sonar blogs) Getting all of the creek in a pass required running the sonar up to the highest possible navigable waters and then a parallel offset course back down. We managed to capture approximately 85-90% of the creek bed and got it towards high tide.

We took a couple extra passes along the Fort Mose area, hoping we might be able to identify possible targets that could relate to the fort’s occupation period. I was quietly hoping we would see lines of submerged pilings or wharfage such as that we identified at the Tolomato site further north. But, no such luck. At least on the passes we took nothing in particular stood out as a ready candidate for further investigation. I do hope to return to the creek with our smaller 14’ boat and re-survey the area in the vicinity of the fort to make sure our towfish deviation didn’t hide anything. Robinson Creek would have, during the period of Fort Mose’s occupation, served as a primary access route to the Tolomato River and therefore has every reason to contain historic debris. Finding it, however, given the centuries of erosion, creek bed shifting, looting, and general site decay may have buried any tangible surviving remains. It is quite possible that the fort maintained a small fleet of fishing smacks, a wharf for these boats, or ‘hards’ used to built, launch, haul, and repair watercraft.

As part of our archaeological marine survey of St. Augustine’s waterways, I hope to soon get out on Hospital Creek. Like Robinson Creek, it was located close to town and has been known for years to be filled with historic debris. Stay tuned as we keep searching the waters of the First Coast!

Bibliography:

Aptheker, Herbert 1943. American Negro Slave Revolts. Columbia University Press: New York.

Deagan, Kathleen and

Darcie MacMahon 1995. Fort Mose: Colonial America’s Black Fortress of Freedom.

University Press of Florida: Gainesville, FL.

Price, Richard 1996 (1973). Maroon Societies: Rebel Slave Communities in the

Americas. Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, MD.

Sayers, Daniel O. 2006. “Diasporan Exiles in the Great Dismal Swamp”.

Transforming Anthropology, 14(1):10-20

Stampp, Kenneth M. 1999 (1989). The Peculiar Institution; Slavery in the American

Ante-Bellum South. Vintage Press: New York.