In the story of the founding of Rome we hear much about Romulus, the progenitor of the ancient city, and little about his brother Remus. Last heard from when passed by a flock of birds doing the god’s bidding in chosing the nascent city state’s king, Remus went underground and was never heard from again. On October 22nd, I met Remus.

(Some images are thumbnails, click on them to see the larger image.)

Heading out the inlet in some moderate chop.

Arriving at the dock at 6:00am I saw the Peter Pirate riding in her slip, waiting to take us out. Our compliment was:

-Cpt. Pierre Pierce and his wife Anita

-Dr. Mike De Luca, Director, Jacques Cousteau National Estuarine Research Reserve

-Dr. Joe Dobarro, Marine Scientist, of the Rutgers Marine Research Institute

-Dr. Rick Gleeson, Research Coordinator, GTM-NERR

The day’s objective was to launch and retrieve an autonomous underwater vehicle (AUV) in order to retrieve data from the sea and sea floor off of the GTM-NERR. The event was a much-anticipated opportunity to explore a partnership between the Rutgers University Marine Science Station, the GTM-NERR, and LAMP. Dr. Gleeson has been coordinating this effort for some time in order to gather biological and environmental data about the offshore waters of the GTM-NERR. The REMUS (Remote Environmental Measuring UnitS) is perfect for this and its class of AUVs has been in service for defense and biological purposes for almost a decade. Recently, a sister REMUS to the one we used on Wednesday was deployed to detect mines in the Persian Gulf after an inbound British cargo ship detected the presence of mines in the shipping lane.

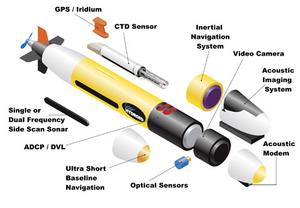

Meet REMUS, our underwater robot.

Instrumentation aboard REMUS.

The REMUS vehicle is capable of surveying 60 nautical miles on one deployment at an optimal operation speed of 3 knots for 20 hours. If sped up to 5 knots its operational timeframe if decreased to 9 hours but can still cover 45 miles of survey line. Instrumentation on the REMUS includes: acoustic Doppler current profiler, conductivity temperature and depth sensors, light scattering sensors, and a 600kHz sidescan sonar. Rutgers has additional instrumentation that can be added such as a plankton sampler. The vehicle design is very adaptable and the manufacturer, Hydroid, tailors each AUV to the client’s specifications based on their needs.

To an archaeologist most of the instrumentation on the vehicle speaks lingua incognitos, since salinity and particulate suspension mean very little to us (with the exception of the decreased visibility!) However, the sidescan sonar attracted our attention very early on since we will be able to compare it to our own Klein 3900 system. One main difference I wanted to investigate is the AUV’s autonomous nature and how this is reflected in the quality of the image. When we went out the St. Augustine Inlet very early on Wednesday morning as usual we hit some standing waves formed by the outrushing tide but the sea state was less than calm once we arrived at the deployment site. We had been following the weather very closely for the week prior to going out and were expecting for the seas to get rougher as the day wore on but the forecast and conditions would have kept us at the dock had we been using a towed instrument. Running the LAMP sonar we require calm seas since we are currently limited to a 21’ boat (soon to be replaced by the 28’ Island Fever once she is re-launched). The more wave action we encounter the rougher the image looks since the fish gets jerked around by its tow cable and a bucking boat.

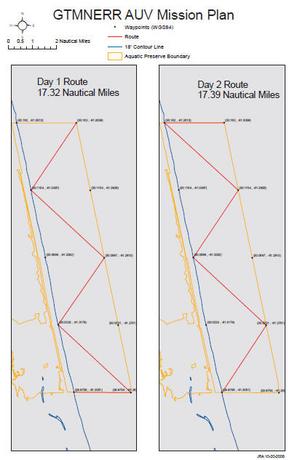

Click on this thumbnail to see the plan of the day. We operated under the “Day 1” plan

On deployment day REMUS was pre-programmed to run transects that were 3 meters above the sea floor keeping it from being submitted to the wave action on the surface. Joe had connected to the machine the day before using a laptop and programming software. He is able to plan out the survey and program it into the machine so it essentially has its ‘orders’ when launched. Our zig-zag survey would begin at the southwest corner of the search area with the fish (slang for the AUV or any other instrument in the water) first completing an easterly course. Upon reaching the southeastern corner of the survey block it would turn from its 90° heading and come to a new heading of 315° (NW). This course, when it finally intersected with the western survey boundary, was then changed to a northwesterly course in order to achieve the ‘zag’ of the ‘zig’. At the northern end of the survey area the fish swam to the center of the northern boundary and then turned south to run a course straight down the center of the survey area. Surveying every square inch of the whole survey block would take a huge amount of time so the project heads designed this survey pattern to maximize time and sample from all areas of the GTM-NERR’s northern waters. Despite the irregular nature of the survey track, scientists refer to it as a non-random systematized search pattern and are commonly used when there is not enough time or resources to cover an entire area.

Programming REMUS for the operation.

The GTM-NERR biological scientists organized the mission in order to begin learning more about their offshore holdings. Data recovered by REMUS allows the scientists to determine water current and velocity, temperature, salinity, bottom types, and particulate content. LAMP is interested in the sonar imagery since this is the first time that area of St. Augustine’s waterways has been investigated by this method. We knew that the survey would be very different than our normal transects which cover 100% of the targeted area but were nonetheless intrigued by getting such a large sample of the sea floor in an area that has never been archaeologically surveyed.

To complete the mission we headed out in the Peter Pirate, a boat owned by Peter Sabo of Camachee Cove Yacht Harbor. Beating our way out the inlet right before sunup we turned north and headed for waypoint #1, the southwest corner of GTM-NERR’s waters. When we reached the spot a buoy way deployed to mark the spot while we readied REMUS. Taking the fish out of its travel case it was hoisted into a specially designed cradle that is used to deploy and launch the vehicle. St. Augustine had already place its mark on the cradle since it had been crushed in shipping but was fixed by Aaron at B&B Welding, also our source for nail rod for the forge.

Deploying REMUS

Pierre sidled the boat up to the buoy and we were ready to deploy the fish. I was standing by with the Ranger, a tracking device designed by Woods Hole Institute and the Navy. The Ranger also acts as a basic control unit, sending simple acoustic signals that can trigger REMUS to begin the mission, abort the mission, come home, go into standby mode, or come to the surface to await further instructions. Joe told me how to toggle the instrument to make REMUS begin its op and as soon as I did so, the propeller began to spin and off the torpedo-like instrument swam. We stood off from the launch area and watched REMUS do its thing. First, it swam three large circles on the surface to calibrate its GPS and compass once it had completed these, the elevator fins on the back depressed and REMUS disappeared beneath the surface.

![]()

The tracking transducer used to talk with the fish.

![]()

Ranger system control unit.

Our next move was to track REMUS to make sure it was headed in the right direction. The Ranger system was again deployed. This unique and simple machine has a weighted transducer that looks like a mini-submarine connected by a waterproof cable to a data box with two simple knobs and a small liquid crystal display screen. By twisting and positioning the two knobs the operator can scroll through all of the command functions. One function is a repetitive ping, broadcast every ten seconds, that signals to REMUS to reveal its location. The AUV sends back a reply message and Ranger can ‘range’ the fish. The operator doesn’t get a bearing on the distance reading to the fish but by moving the boat and pinging REMUS from more than one location you can figure out where the fish is and where it is heading.

Watching a shrimp boat try to occupy the same space as REMUS.

Throughout the course of the day we moved from one waypoint to the next, making sure that REMUS was on course and on time. With a little sargassum (seaweed) in the area we were concerned that it may foul the propeller and with the beach just a few hundred yards off we didn’t want the AUV going ashore and getting pounded in the surf. Joe did tell me that the British Navy lost a REMUS unit and after thirty days of floating in the North Atlantic, it was found washed up on a Norwegian beach. Stripped of everything that protruded from the pressure hull (fins, GPS mast, etc) it was still holding data it had retrieved from its initial mission and the Brits were able to recover everything. Nonetheless having an AUV going on a ‘drinking binge’ and getting washed up in-between surf fishermen would be an ignominious moment for us and so we watched carefully as REMUS made its turns and came onto a new course. I was particularly surprised at how accurate the dead reckoning system is which REMUS relies on to get around underwater. Each waypoint was reached within a couple minutes of its estimated arrival time. We knew this from Ranger’s tracking ability and the fact that REMUS, upon reaching each waypoint floats to the surface for a minute and a half to get a fresh GPS fix. So, for a brief period the range readings on Ranger should stay roughly the same indicating REMUS’s stationary nature.

Looking for REMUS to appear and recalibrate its GPS navigation.

The team from Rutgers to not always babysit REMUS like we did last week. In fact, very often they will deploy the fish and then return to the dock to wait until it needs to be picked up 12 or so hours later. The risk you run with this is that if something goes haywire with the machine such as the prop getting fouled or the machine is hit by a boat while momentarily on the surface you will not know it. Fortunately Hydroid has built in a solid backup system and REMUS will send a distress ping for thirty days to track it by. Joe also placed a blinking light on the top of the fish so it can be seen at night if on the surface and in a distress mode. One time they have had to track it using the Ranger system, which is good out to about 4,500 meters. After a search pattern run near Myrtle Beach they think a shrimp boat snagged the fish and dragged it way out of the survey area, ultimately either dropping it from the net or having hauled back and then pitched this unusual catch overboard. Joe and his team found REMUS drifting towards a breakwater surrounded by Coast Guard boats establishing a protective zone around this dangerous-looking terrorist-like atomic-powered white-powder-carrying torpedo.

![]()

Using the Ranger system to end the mission and send REMUS to the top for recovery.

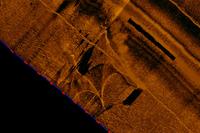

Last Wednesday we has a close call and were glad to have been on hand to act as mother goose. When REMUS was approaching waypoint #4 we realized that the waypoint location was currently being occupied by a shrimp boat busily dragging her nets. We deployed the Ranger system and confirmed that REMUS was about to try and occupy the same space with the law of tonnage heavily favoring the shrimp boat. With toes curled and fingers crossed we watched the range on REMUS decrease as it approached the dangerous intersection and then swam away apparently unharmed. We were prepared to hail the shrimpers on the radio and request that they haul back to recover their most expensive trawl ever. We knew that the shrimp boat encounter was a close call but not until we reviewed the data did we realize how close. The shrimp nets trawled right in front of REMUS and at the closest point the two were about twenty feet apart!

The sonar image REMUS took of the offending shrimp net. Note the double nets, otter board trawls on the right hand side of the net and the two bags of catch at the end of each net.

The rest of the day went pretty much without incident and the only change to plans was an early retrieval of REMUS since the sea conditions were deteriorating. The final run back to the dock was made and we were met by the St. John’s county film crew who were on hand to interview Dr. Gleeson for the government television channel.

The next day the GTM-NERR staff met to discuss the previous day’s mission. Joe gave a presentation of the machine’s capabilities to those who couldn’t make the offshore operation and had a nice visual display of the data. I had a chance to download the sonar data and begin the mosaic in SonarWiz.MAP, a software both Rutgers and LAMP use to create composite images of acoustic data. We were also able to see the image of where the shrimp net almost caught REMUS, a picture that would make even the most stalwart AUV operator weak in the knees!

Overall, the REMUS operation was a fantastic experience to work with other professionals in the field and gain a better understanding of how they go about their work in data acquisition and post-processing. Joe, Mike, Cpt. Pierre, Anita, and Rick were all wonderful to work with and I look forward to seeing REMUS back in St. Augustine.

The REMUS crew for the day, minus Dr. Gleeson.

Brendan and REMUS