Digging through the online archives of the Library of Congress, I recently came across a panorama of St. Augustine completed in 1855. After close review, there are some interesting details I thought I’d share with the blog community.

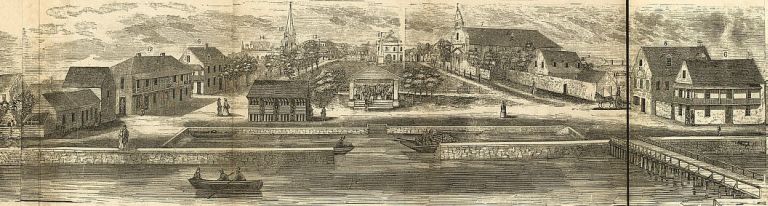

Boatbuilding in St. Augustine, as with any historic port, has been a necessary industry for exploration, commerce, and transportation. Here at LAMP, in order to better understand our maritime past, we are continually searching for clues about this past. Recently, in searching through Library of Congress imagery on St. Augustine, a panoramic wood-cut of the city was found that offers some helpful hints as to how the city appeared during the mid-19th century and what sorts of boats were plying the city’s waterfront. The image, produced by prominent New England wood engraver John S. Horton, was part of a popular mid-19th century practice of creating panoramas of city waterfronts. This type of image gave the 1850s viewer a realistic presentation of a city that many of us now rely on the internet searches, visitor’s pamphlets, and pictures to provide.

The era of photography in 1855 was highly developmental and large-scale landscape images were unheard of. Readers of Harper’s Weekly and other popular magazines had woodcuts and lithographs to supply interpretations of national events. Even during the Civil War drawings and cuttings were the primary means of publishing pictorial news. Traditional maps only depict in two dimensions but the panoramic drawing offers scale, moderate to good accuracy, and most importantly, the third dimension of relief. So, for St. Augustine to get exposure to a nationwide audience as a proud city that had real buildings, real people, real business, and real beauty the panoramic woodcutting was the way to go.

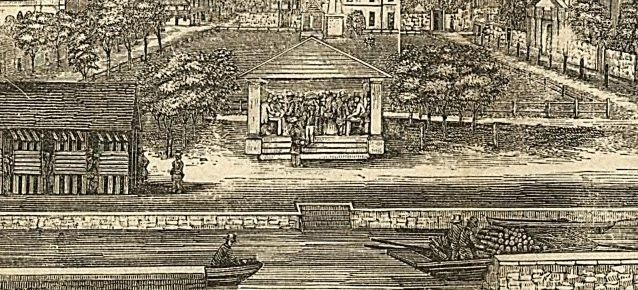

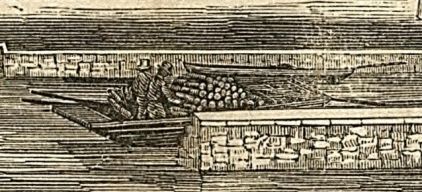

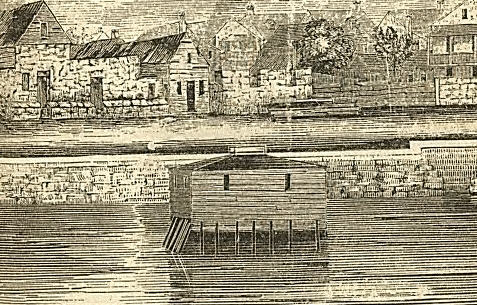

As we take a look at this wonderful image, we note several features which were distinct to mid-19th century St. Augustine. In the front and center of the cityscape is a basin, a cut and dredged area off of the Matanzas River in which small boats could dock to load and unload cargoes. Visitors to town could also use this area to temporarily dock their boats in order to transact business. Note on the right hand basin retaining wall at the entrance, that the stone appears to be laid in a stair-step fashion around portions of the interior of the basin. This would provide nice moorings at any tide. Think of this little basin as a public parking, much like that spaces along the town square today. I also imagine that boats overstaying their welcome may have been subjected to various sorts of censure, perhaps even having their docklines cut! However, close inspection of this dockage show is that inside the basin are three boats. Artists creating such imagery during the 19th century were often careful to not only depict the physical manifestations of buildings, streets, and waterways, but added cultural detail that 2D maps cannot usually provide. Thus, we see what appears to be two gentlemen (note the stovepipe hats) having a discussion in their well-laden boat just to the right of the entrance. This vignette, while certainly a impression of the artist and not a detailed photograph, does offer details about the city that we would otherwise have to create from written records. And who is to say that an event just like this did not actually take place while the artist was drafting sketches to base his cutting on?

Looking a bit farther to the left, or south as it were, we note two more boats in the basin. The prow of one skiff is reveling itself from behind the retaining wall and appears to be somewhat round-nosed. The second boat, to the rear and left of the basin entrance, appears to have two seats, and possibly have at least one square-end. In front of the basin we see two men pulling at the oars to deliver a top-hatted gentleman to the dock. This may have been a ferry or other small boat for hire used to carry people about the town’s waterfront or convey them up or down the rivers to local houses and plantations.

We note, too, that many of the prominent town buildings are labeled. In the center of the picture is the Government House, labeled as “15. Court Houseâ€. The St. Augustine Cathedral is also located on the square under the title “7. Catholic Church†and portrays the building prior to its later modifications. Moving across the square we see a house, identified as number sixteen, the “V. Lanchez†house. This error, since ‘Lanchez’ is probably meant to be Sanchez, illustrates how cultural data on maps is completely reliant on accurate recording on the behalf of the cartographer. Likewise, most maps created are not done so by natives to the area and also rely on good local informants to provide accurate spellings, concise locations, as well as boundaries.

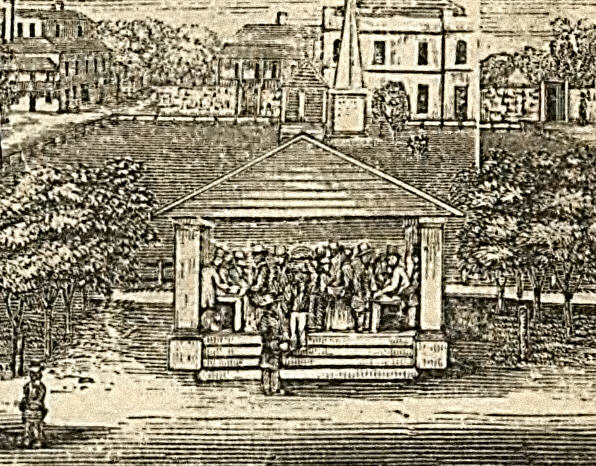

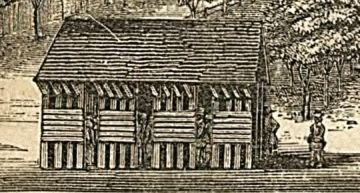

Front and center is a small building that still stands in the Plaza. Mayor Thomas H. Penn was responsible for the construction of the marketplace in 1824. At the time of this panorama the marketplace would have fronted the basin, allowing fishermen for unload their catch for sale in the public market. To the left of this structure is a unique building which appears to have no visible windows or chimneys and seems to have a door on the northern gable end where an two men appear to be talking. It seems as though this building may have been used as a stockade to hold slaves prior to their sale at the market. Debate has raged on about whether or how regularly slaves were actually sold at the marketplace, however it is known that many thousands of slaves were imported into St. Augustine, over a thousand in one year during the British period (Harris 1918). In addition, St. Augustine Historical Society historian Dr. Susan Parker has identified a number of references in the documentary record of slaves being sold at this market. Cursory examination of the scene depicts something like preparations for a slave auction. We can see tables set up in and people haggling over prices as they are wont to do in a market. This illustration is exemplary of how a panorama conveys the goings-on of a town to the outside world through the artist’s eyes.

Looking towards the fort we see the “Bathing Houseâ€, an artifact of the Victorian Era during which modesty concerning the public human form was paramount. These buildings allowed well-dressed bathers to ‘take the waters’ without causing offence or being branded obscene. One must wonder how enjoyable bathing in the Matanzas River must have been at the time when raw sewerage was regularly flowing into the city waterfront! A picture taken of the town during the 1870s by famous stereograph photographer Rufus Morgan shows the bathing house still in place.

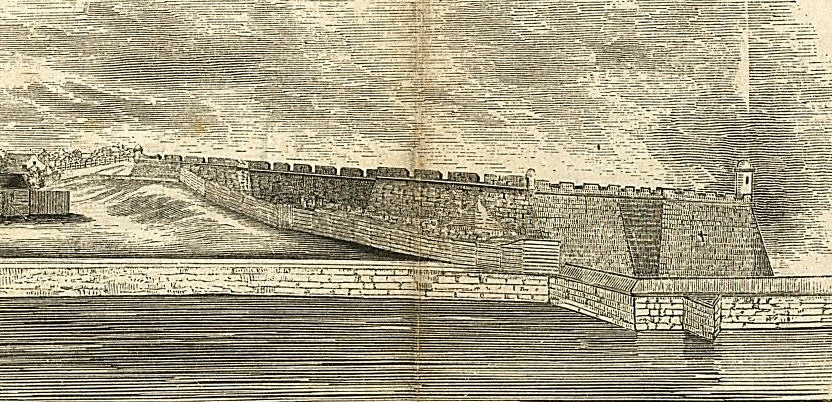

At the far right of the picture, the Castillo de San Marcos is prominently displayed as the colonial monolith it has always been. Attempting to portray the immense and dominating nature of the fort, the artist has projected it so it almost appears to thrust itself into the foreground and onto the waterfront. Again, this was all part of projecting a 3D reality onto paper so someone a thousand miles away could see St. Augustine and study some of it sundry details.

There is another facet to the panoramas of the 19th century. Art historian Shelley Rice notes that after the late 18th century introduction of the panorama by Irish painter Robert Barker panoramas took off all over Europe. By mid-century she observes that all major European capitals had structures built, some very elaborate, to display traveling canvas panoramas. Typical themes of the panoramas focused on travel, Biblical events such as the crucifixion, and epic battles. We may now think of these panoramas as an early attempt at a multimedia presentation. The concept behind the 360 degree panorama was to take the viewer there, to have them experience what was imprinted on canvas. Many unique types of display were used to enhance the experience, including a fading upper relief and shrubbery placed in the intervening space between the viewer and painting to add depth and reality to the scene.

The panorama we see here, albeit not 360 degrees nor in color, still performed a similar task. Allowing the viewer to ‘travel’ with the artist to see St. Augustine was part of the intent of the panorama. Similarly, as the industrial revolution progressed and matured through first two quarters of the 19th century artists were employed to depict the industry of a locale. Favorable renditions of such urban vistas reinforced connotations of progress in an empirically secure world. Secondarily, successive panoramas of cityscapes could foster notations of emergent positivistic thought that would ultimately drive the way Victorians viewed and constructed their environs.

So, we see a simple image containing thousands of bits of information. The way in which the information is combined, however, is unique and has rich anthropological meaning. To see the panorama for yourself, go to the following link:

http://memory.loc.gov/cgi-bin/map_item.pl