Today I am a member of the Green Team. All of the students in the Flinders maritime field school have been divided up into three groups—the Green, Red, and Yellow teams. Each group of 3-4 students will work at one of three different areas—the Star of Greece wreck site at Port Willunga, the nineteenth century baths and pier at Victor Harbor, and the Showboat wreck and pier remains at Hindmarsh Island some 20 km east of Victor Harbor. Each team will rotate so that everyone gets to work at each of the three areas.

Today I will be diving on the wreck of the Star of Greece. This iron-hulled, three-masted sailing ship was one of the fastest and most renowned ships in the Star Line. She was 1227 tons and built in Belfast, Ireland in 1868. The picture below comes from a contemporary painting of the ship.

On the 13th of July 1888, while bound for Great Britain with a cargo of 16,000 bags of wheat, the Star of Greece was wrecked during a fierce gale. Even though the wrecked ship had run aground only about 100 meters from shore, the lack of adequate lifesaving facilities and the severity of the storm lead to the deaths of 18 crew members.

Today, Port Willunga is a popular beach. You can see why in the pictures below:

In the 19th century a long pier or “jetty†was in place at Port Willunga, seen in this historic photograph. This terminology seems funny to me, as in the U.S. a jetty refers to a breakwater made up of stone, while a wooden structure on pilings such as this one would be called a pier. The Port Willunga jetty was used to facilitate the export of agricultural and mining products from the interior.

Today, all that remains of the jetty are a series of wooden pilings on the beach, extending out into the water.

North of the old jetty by about a half mile is the site of the Star of Greece. Here, the Flinders University students making up the Green Team have set up a beach camp. During the first week of the field school, no boat is available, so we are staging our dives from the beach. The hardest part about this is lugging all of the equipment a half-mile from the closest beach access. We have a pull-cart to help with that, though by next week a boat should be available and that will make the transportation of equipment directly to the dive site much easier.

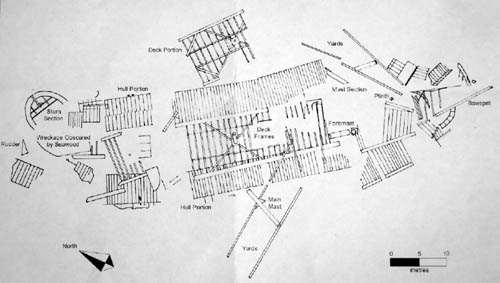

I first joined the Green Team yesterday, which was their first dive on the wreck. I swam out to the wreck site while divers were down, and enjoyed snorkeling around the iron wreckage. While the ship has completely broken apart, large sections of hull and other components such as iron masts and yards and an enormous rudder remain intact in about 15 feet of water. The vessel’s stem, or forwardmost part of the bow, protrudes up from the seafloor so high that it breaks the surface of the water and is visible from the shore. This site has been surveyed by archaeologists between 2001 and 2003, and their site plan delineates the major components of the shipwreck.

Even though this site has been mapped before, and is being used for training purposes, there is always value in re-recording shipwreck sites. Ongoing inspection will let us know how the wreck is changing over time, and might reveal newly exposed areas or artifacts or signs of deterioration, vandalism, or looting. The students have been charged with recording this site, and it is up to them to determine the best way to do so. To successfully meet this goal they will have to plan as a group what their methodology will be, and what tasks are to be completed for each dive. Here, Flinders masters student David Kalinowski and PhD student Claire Dappert plan their dive on the beach before kitting up and entering the water.

After swimming out to the site, they descend down amid the wreckage, which is shrouded in a thick layer of marine growth.

David uses mylar, or underwater paper, taped to a slate in order to write down measurements they take on the shipwreck. The two divers can also use the slate to write messages to each other, though pre-arranged hand signals are the quickest way to communicate.

Meanwhile, at the stern end of the shipwreck, Flinders masters student David VanZandt and Agnes Miloka hammer in a steel pin in order to lay out a baseline.

The baseline consists of a tape measure stretched out for a specific distance and secured at each end. This is used as a reference line, and measurements taken from it to various pieces of the wreck can be plotted on a master site plan after the dive.

During the dive, I also take some time to explore the wreck on my own. This is simply a very cool wreck. There is so much structure remaining, and it is completely covered in sponges and other marine growth, and teeming with fish life. I especially liked this picture taken at the stem or bow of the vessel.

A large stone monument has been placed amid the wreckage, with a sign explaining the history of the Star of Greece and its wrecking. It serves as a sobering reminder that 18 men lost their lives here. Behind the monument is a large iron yard—one of the cross-pieces that hung from the masts and held the square sails aloft.

I also took this self-portrait, for those of you who haven’t had the pleasure of seeing me underwater:

After the dive, we all swim back to the beach. The students seem confident that they have accomplished the goals they have set out for themselves, and I have enjoyed my time on this spectacular shipwreck. Tonight, instead of heading back to Willunga, I’ll be traveling to Victor Harbor, where I’ll be staying for the first time with the rest of the students. While I’ve certainly enjoyed diving on this wreck, I’m looking forward to seeing some of the other sites that the Red and Yellow Teams have been working on.